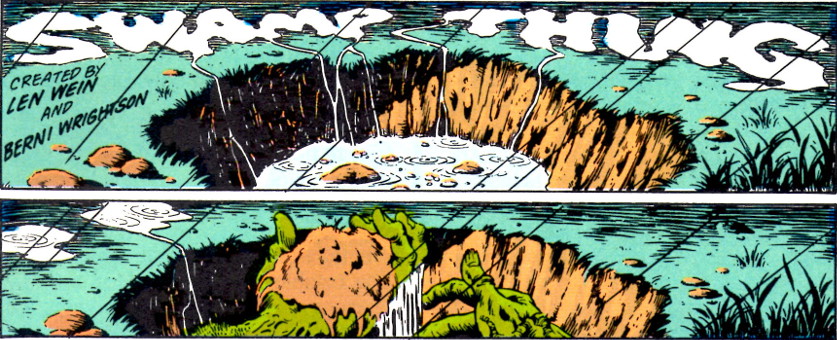

In this final installment of the exploration of Alan Moore’s work, I’m going to show examples from his early run on the Swamp Thing. Although Moore has done a great deal of work that is critically acclaimed (V for Vendetta, Watchmen, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, etc.) he really made his mark with Swamp Thing, which remains his best work.

It is also the work most germane at the time he wrote his treatise on comic book creation that was covered in the last two posts, and most of his techniques are visible in his tenure on that book.

The material below is from his first two years on Swamp Thing, which span issues #20 – #43. My sources are the collected trade paperback reprints, some of which are almost as old as the run itself. I find that Moore’s stories are best enjoyed without the interruption of advertisements and other various distractions (letter pages, inside covers, etc.), since his stories are predominantly about mood and atmosphere.

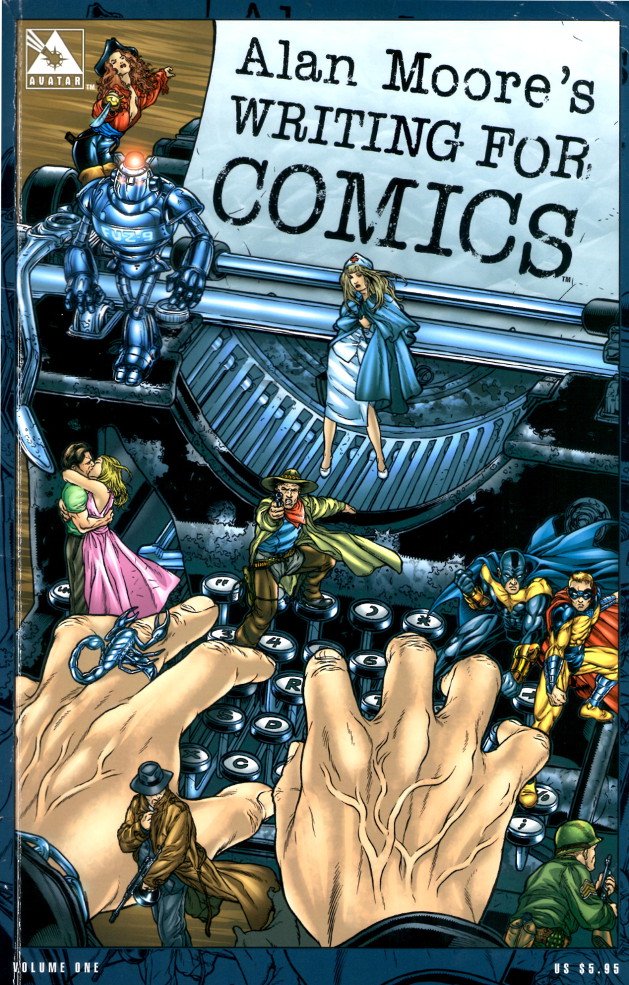

Moore’s central ideas from his Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics were: to focus on a story concept; build a structure that matched; worry about transitions; worry about pacing and flow; and put in plot and dialog last. These five main points will be covered in turn below.

Story Concept

The first point that Moore raised was the idea of having a relevant story to tell. By relevant, he means one that has some meaning to the reader – a fascinating idea, a socially important tale, and so on.

For Swamp Thing, Moore chooses as his basic idea the concept that the Swamp Thing is actually a hybrid between man and plant, having the physical and essential properties of a plant but with the memory, consciousness, and intelligence of a man. With this basic idea at their core, the subsequent tales all fall into the perspective of man’s interaction with the plant world.

To flesh out this idea, Moore has to connect the scientist, Alec Holland, whose coincident death with the Swamp Thing’s creation leads all to think the two are the same entity, with the plant-thing-that-thinks-itself-a-man that he was creating. Here Moore drew on the existing ‘science’ of cannibal planarian worms (as explained in issue #21 by the Floronic Man)

to establish how even the Swamp Thing could believe that it was Alec Holland. Published in the early 1960s, this science was largely discredited even though the sensation it created lingers to today. Whether Moore was impressed by this story and reworked Swamp Thing around it or whether he wanted a plant-human and found the science convenient is unknown to probably all but him.

What is clear is that this simple idea forms the core of almost everything that he writes afterward. By making the Swamp Thing truly a plant, Moore can draw a huge number of new ideas all from a single premise. The Swamp Thing is now a plant elemental who speaks for the entire plant kingdom and, in some sense, for the earth itself.

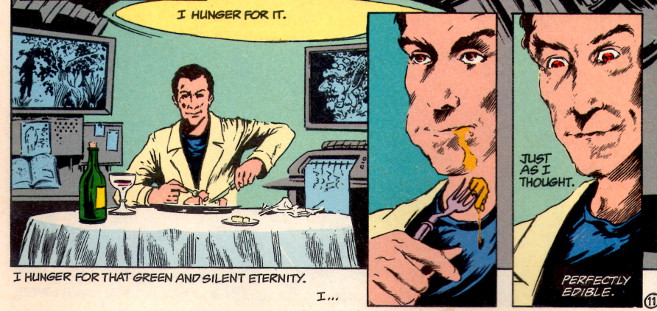

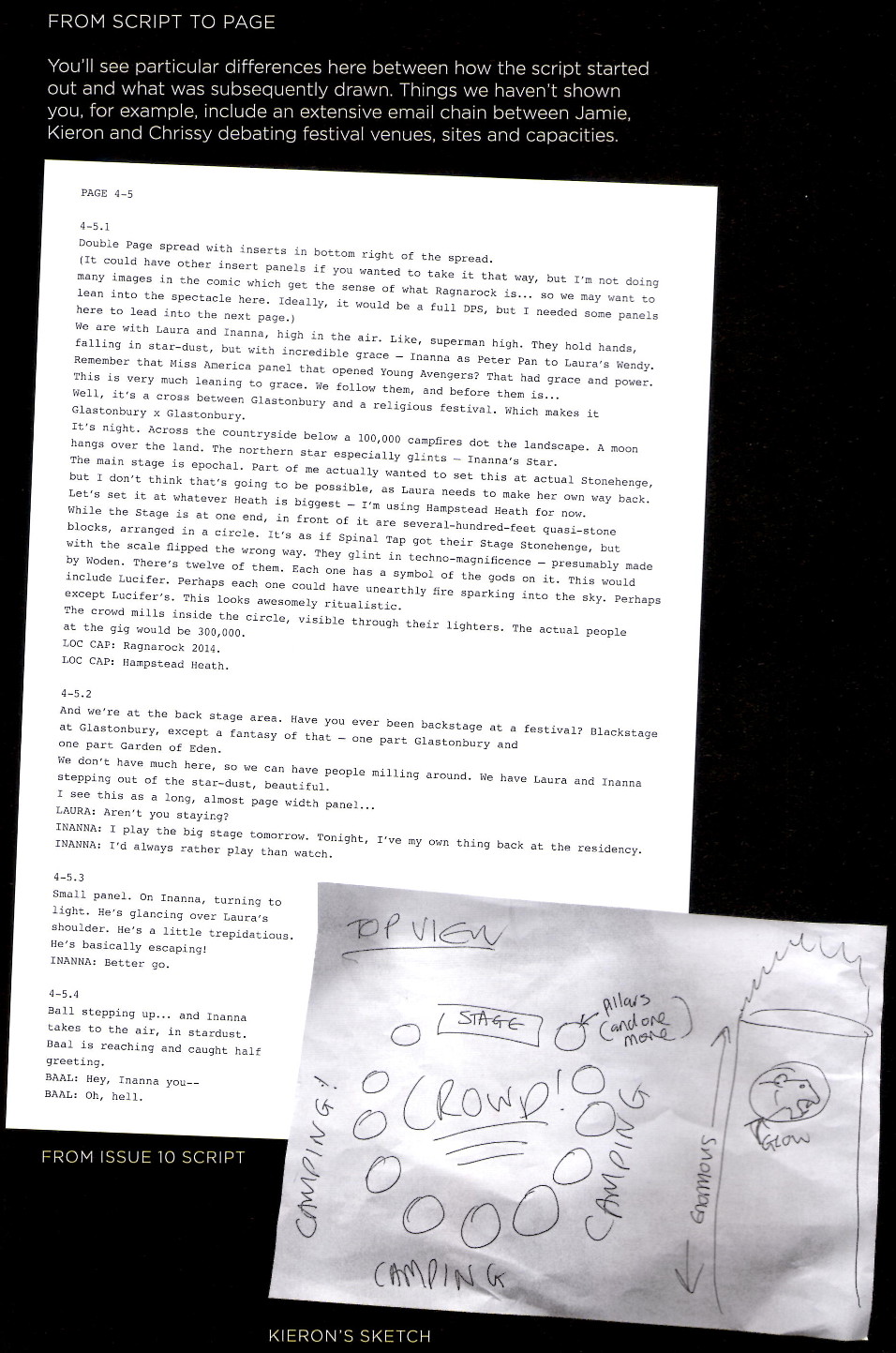

One of the more fruitful lines of concepts is the reoccurring notion of eating a vegetable substance produced by the Swamp Thing

and the Floronic Man’s consumption of these tubers allows him to have some access in the awareness that the Swamp Thing possesses as an avatar of that portion of nature known as ‘The Green’.

This in turn drives the Floronic Man mad so that he orchestrates the subsequent, horrific events that fill the plots of issues #22-24.

Later on, the idea of consuming a portion of the Swamp Thing plays out in many different ways. Two of them are particularly notable as they comprise reoccurring ideas.

In issue #34 the Swamp Thing wishes to have a ‘sexual communion’ with his love interest Abigail Cable but being composed of plant matter, he lacks the necessary anatomy. As an alternative, he produces a fruit that when consumed takes Abigail on a psychedelic trip through his awareness. The lovers join on a spiritual level and their version of marriage and union is established.

In issue #37, the Swamp Thing begins to learn that his consciousness exists independently of the plant matter that forms his physical shape. As a result, if his body is consumed by fire or damaged by toxins, he can abandon it and regrow a new one. This then leads to his ability to transport himself, almost instantaneously, anywhere in the world. This handy trait not only allows him to respond to emergencies world-wide, but it also opens the door for subsequent explorations of consciousness and soul.

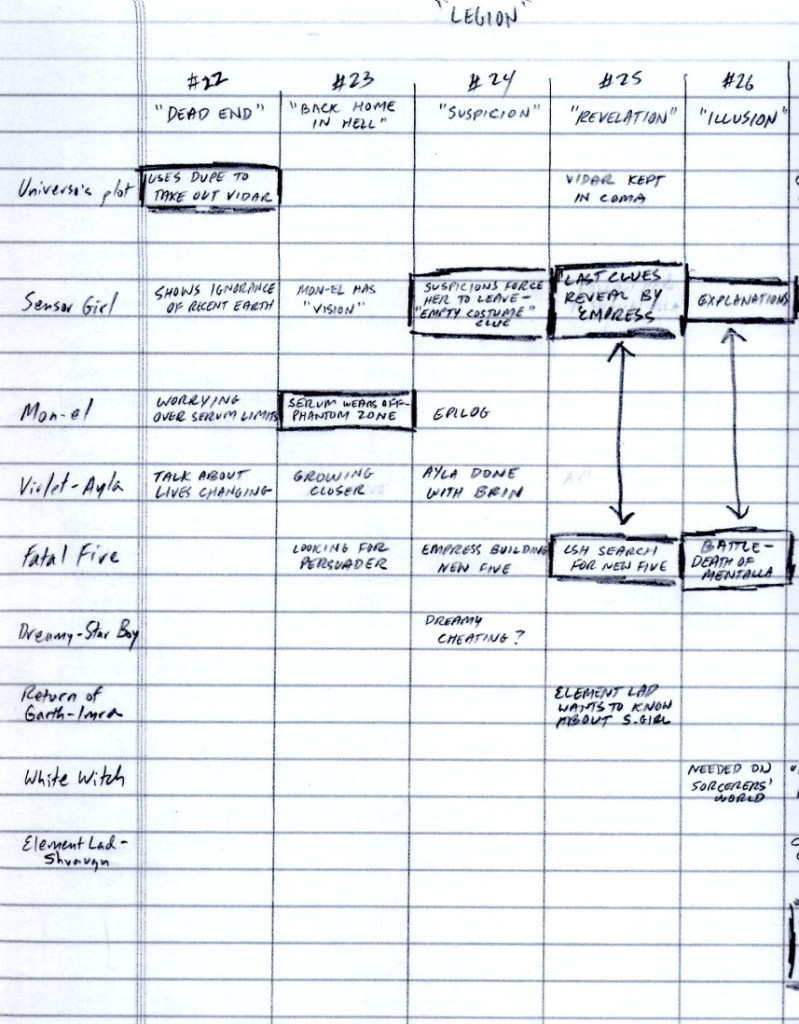

Story Structure

Moore spoke of several story structures, but the one that he seems to favor is the idea he calls elliptical, where the events at the beginning of the tale match, in some fashion, those at the end.

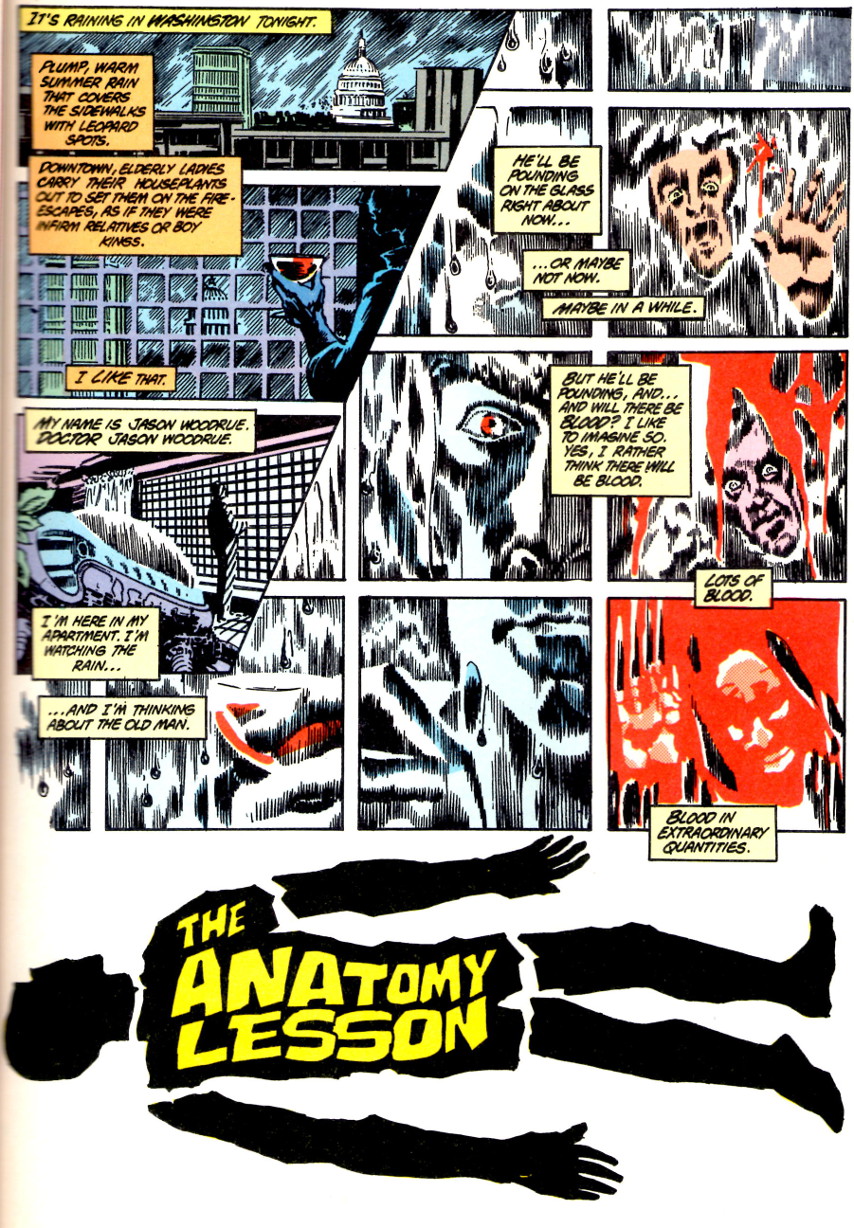

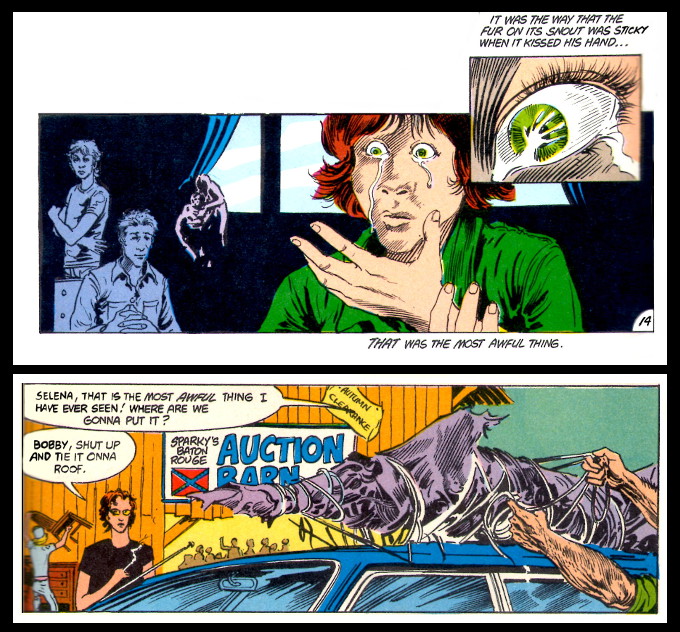

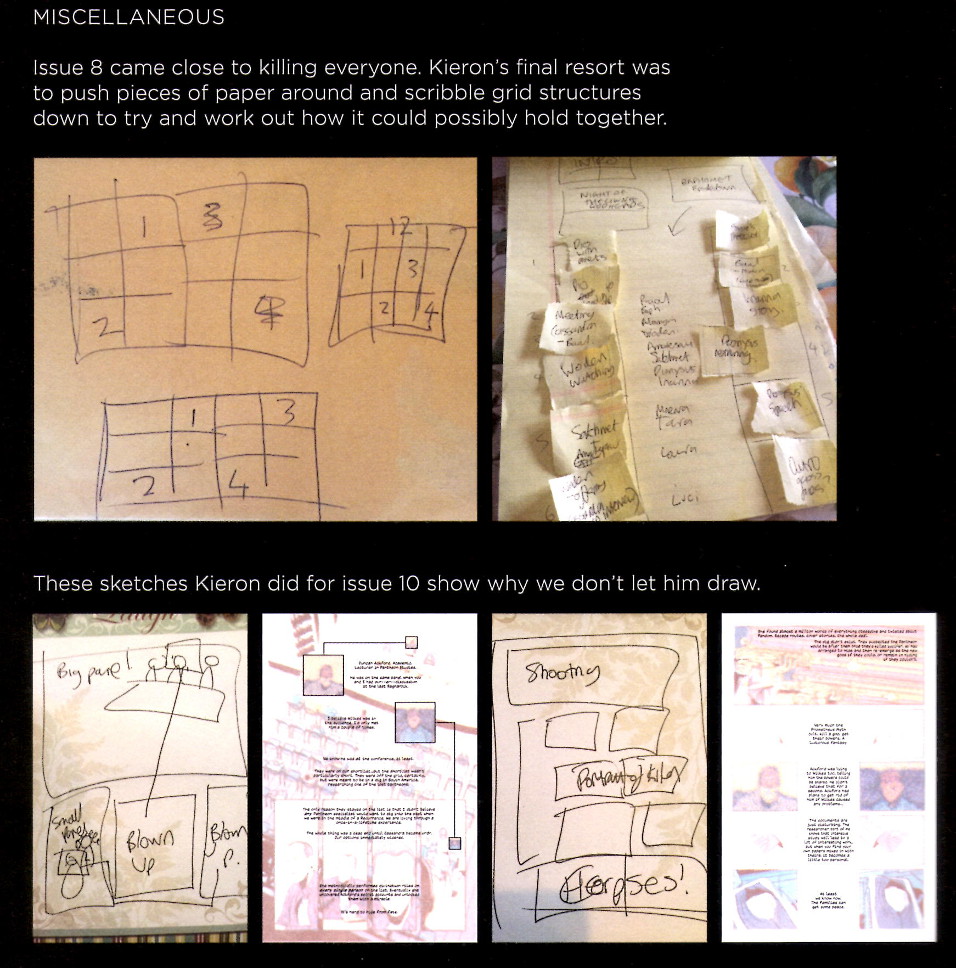

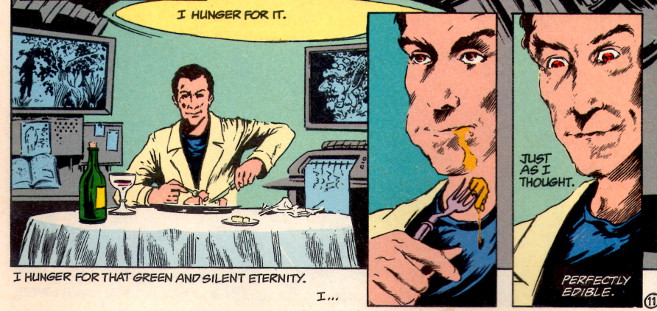

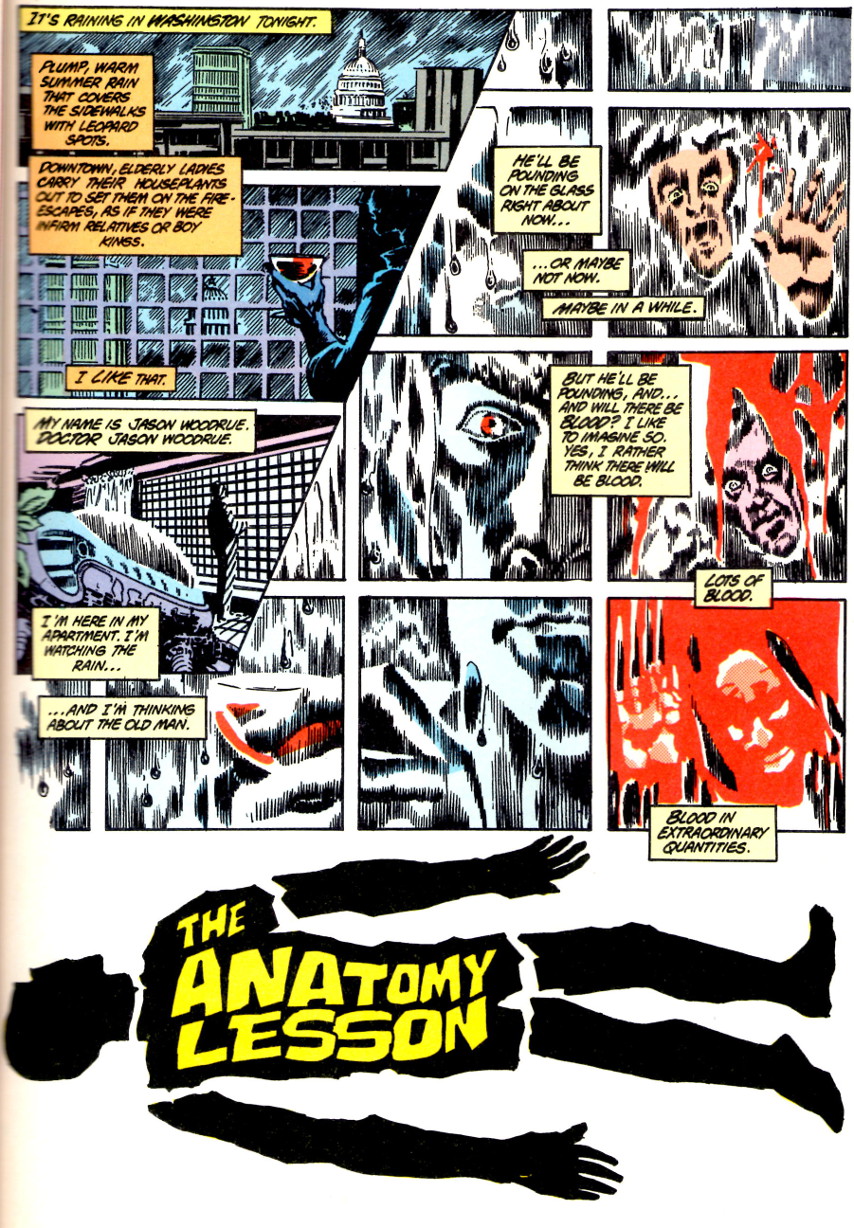

The image below is a reproduction of the first page of Issue #21, which starts with “It’s raining in Washington tonight.” and shows the Floronic Man reflecting on the events of the day through a finely paned window.

The image below is the last page of the same issue showing the same structure verbally and visually as the opening page. Note the subtle changes in the appearance of the Floronic Man’s reflection in the panes and the bookend placement of the “It’s raining in Washington tonight.” to close the issue.

Another structure Moore suggested is the gimmick where a central piece is used to build the rest of the story around it. In Issue #35, the reoccurring motif of the newspaper articles form the backbone in both the visual imagery and the background information needed to convey the impact toxic waste has on the environment.

Transitions

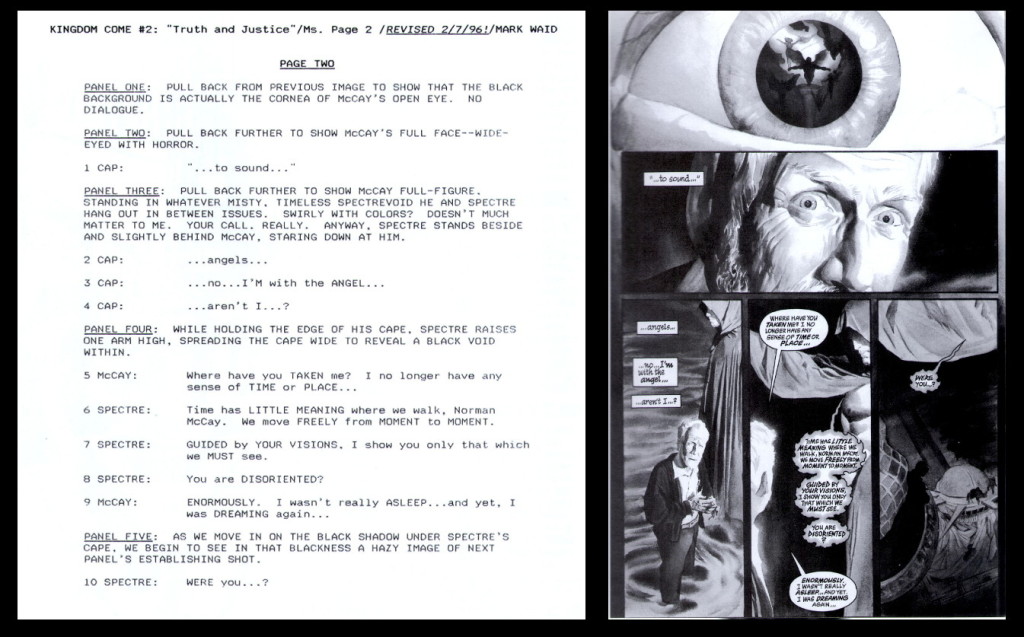

In his book, Moore spends a lot of time discussing transitions. His concern, seemingly above all else, is that a bad transition will break the spell under which he has placed the reader. As a result, much of his work shows an attention to this point.

His approach is to think about storytelling in units of a whole page with the transitions linking the pages together. The most common linkage is verbal, where the same word is repeated between the last panel on one page and the first panel on the subsequent page. Often the word is used in different context or with a different shade of meaning, thus mimicking the way the brain connects disparate notions of a word together to create humor or double entendre.

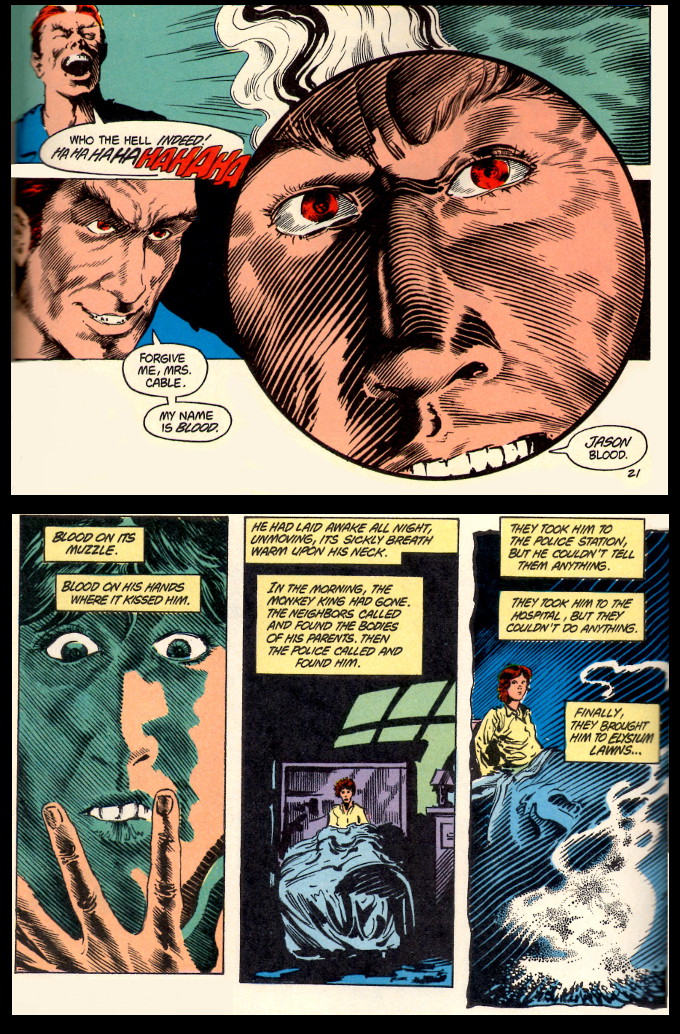

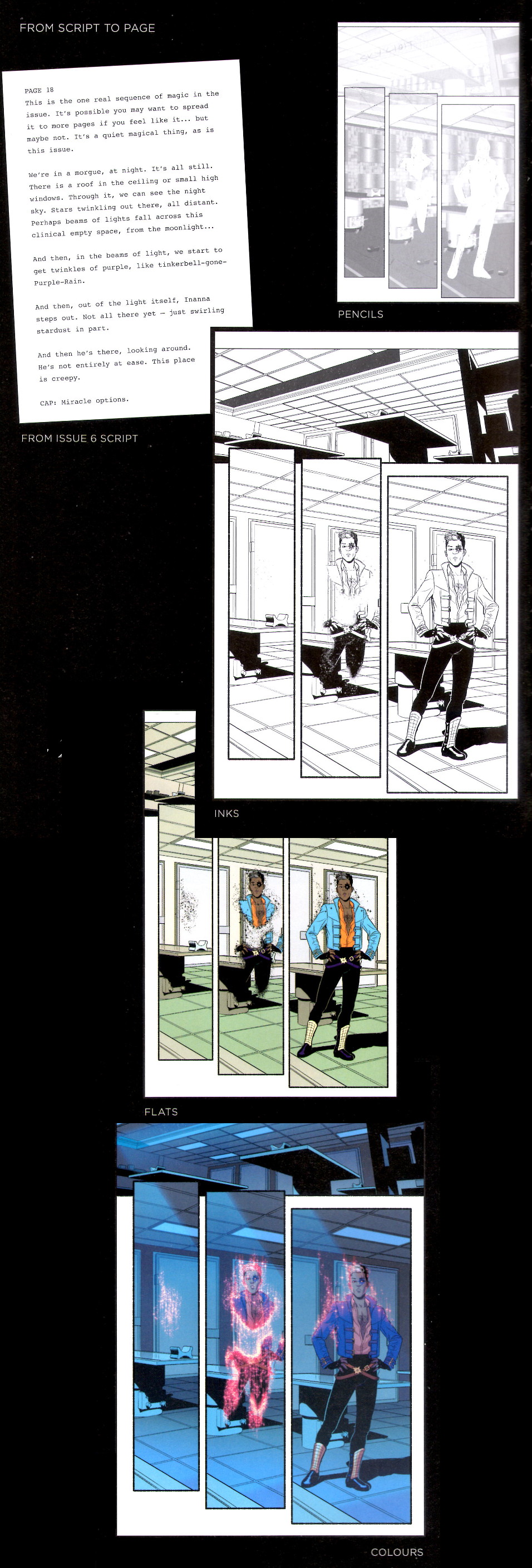

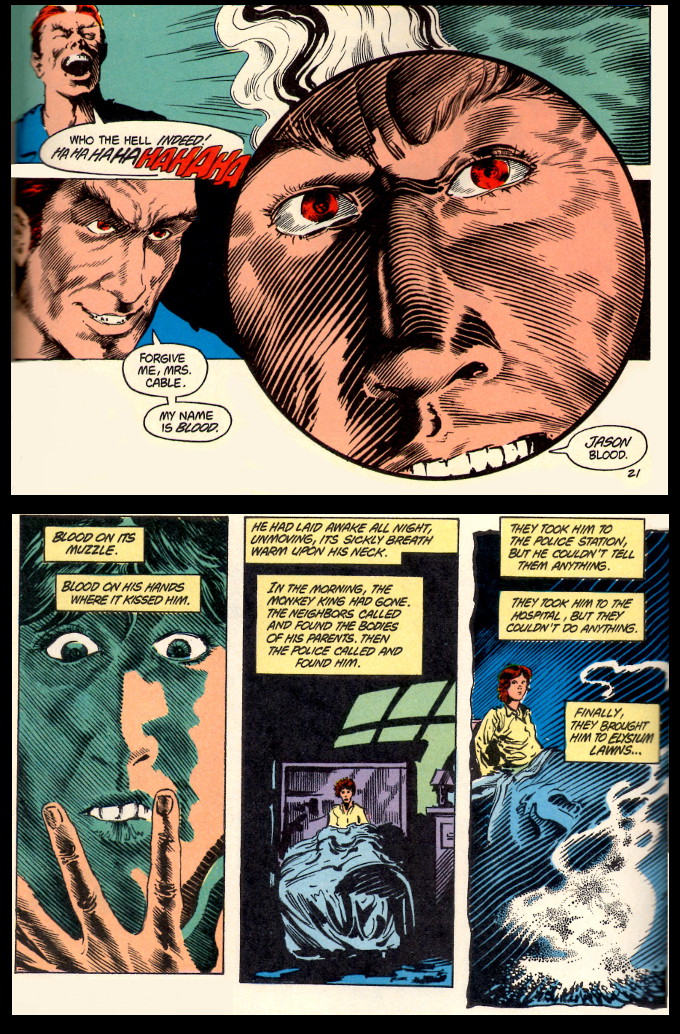

The following image is a transition between pages 21 and 22 in #Issue 25.

Note the use of the word “blood”, first as a last name, second as the substance, to link two different threads together.

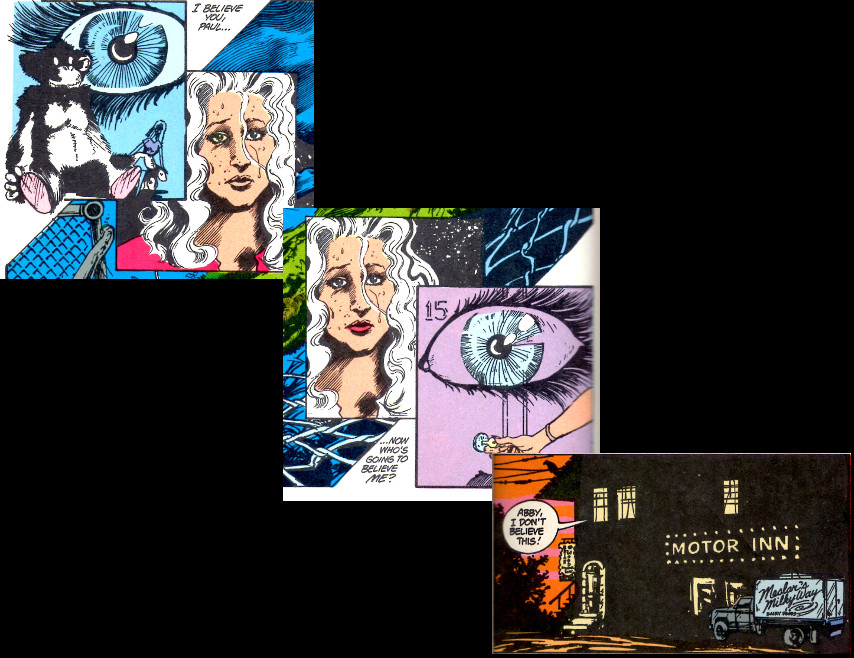

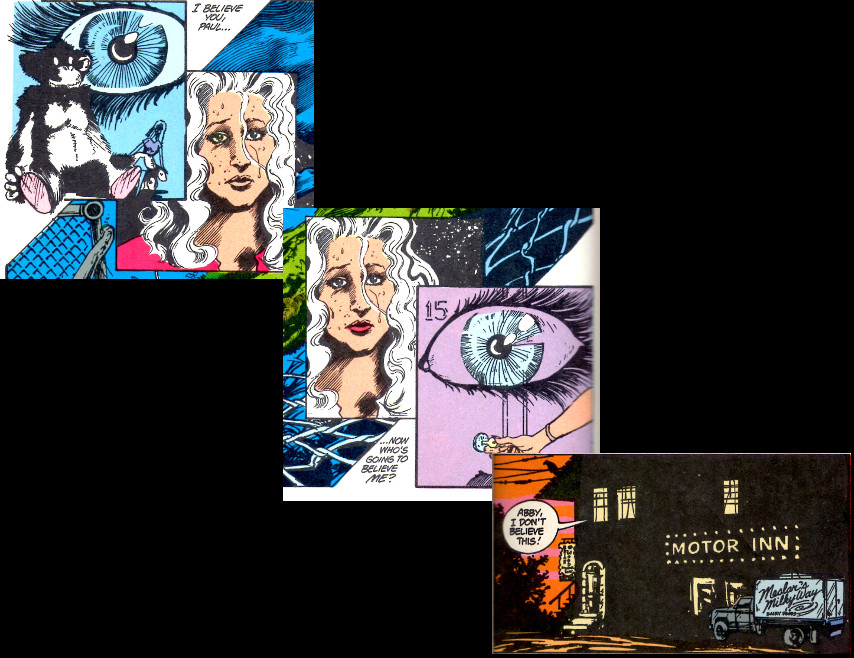

Verbal transitions also provide larger linkages. The following example comes from pages 11 and 12 of Issue #26. The first two panels come from page 11 and are in the relative orientation on the page; the first one being on the top left, the second being on the bottom right. The word “believe” links the change in mental state of Abigail as she ponders what a young man has told her. The word “believe” also links her realization to her subsequent discussion with her husband Matt (note Matt is soon after done away with to make room for the Abigail-Swamp Thing romance).

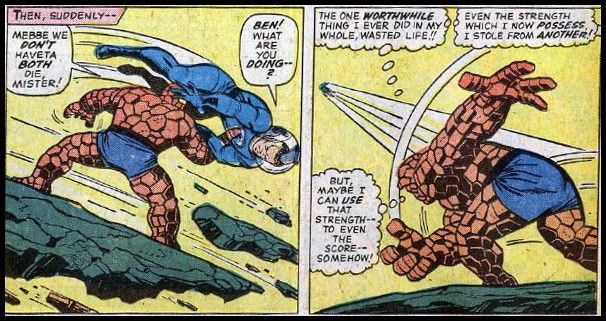

Transitions can also be used to provide linkage between larger entities. This is the well-known ‘cliff-hanger’ end to comics where a scene at the end of one issue is essentially the same as opens the subsequent one. That said, the transition between issues #30 and #31 with the Swamp Thing holding Abigail’s body is particularly well done.

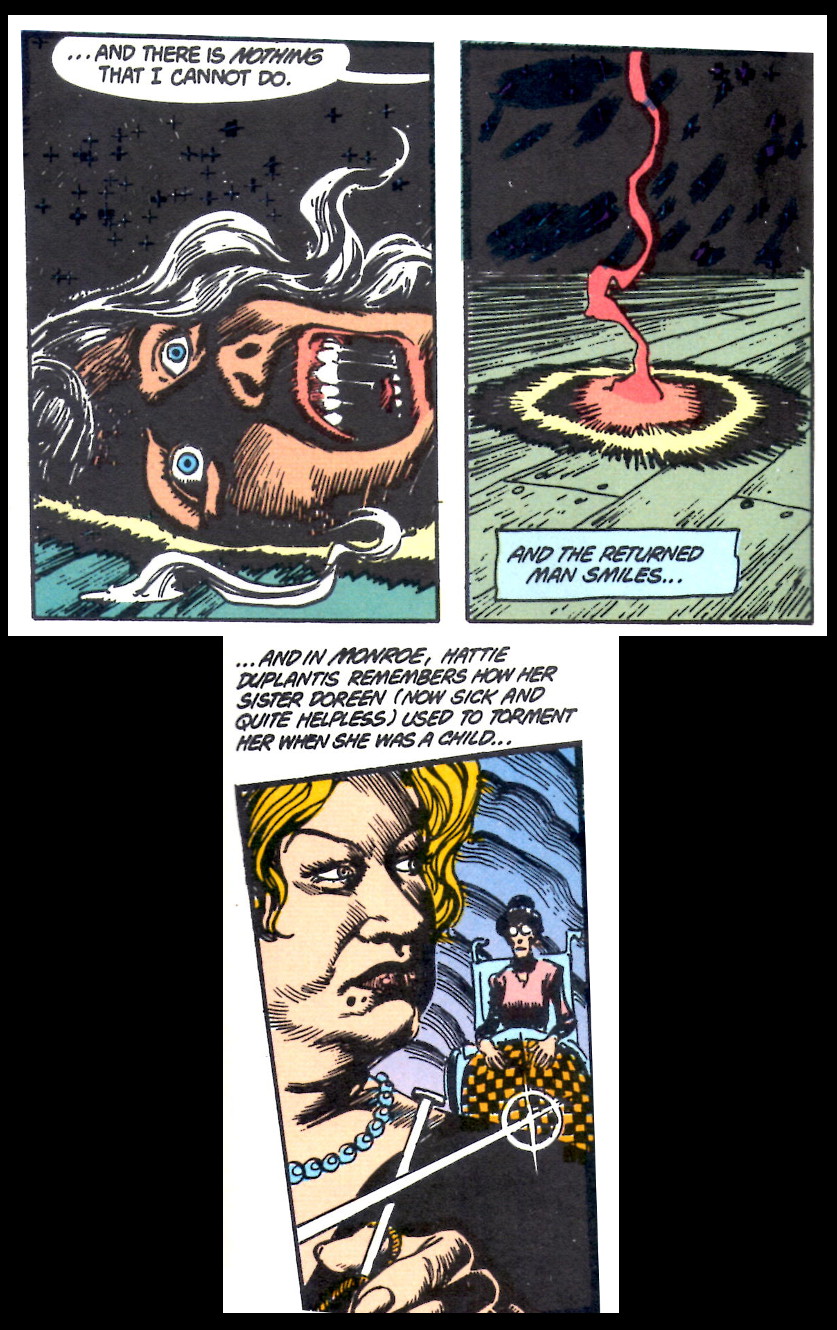

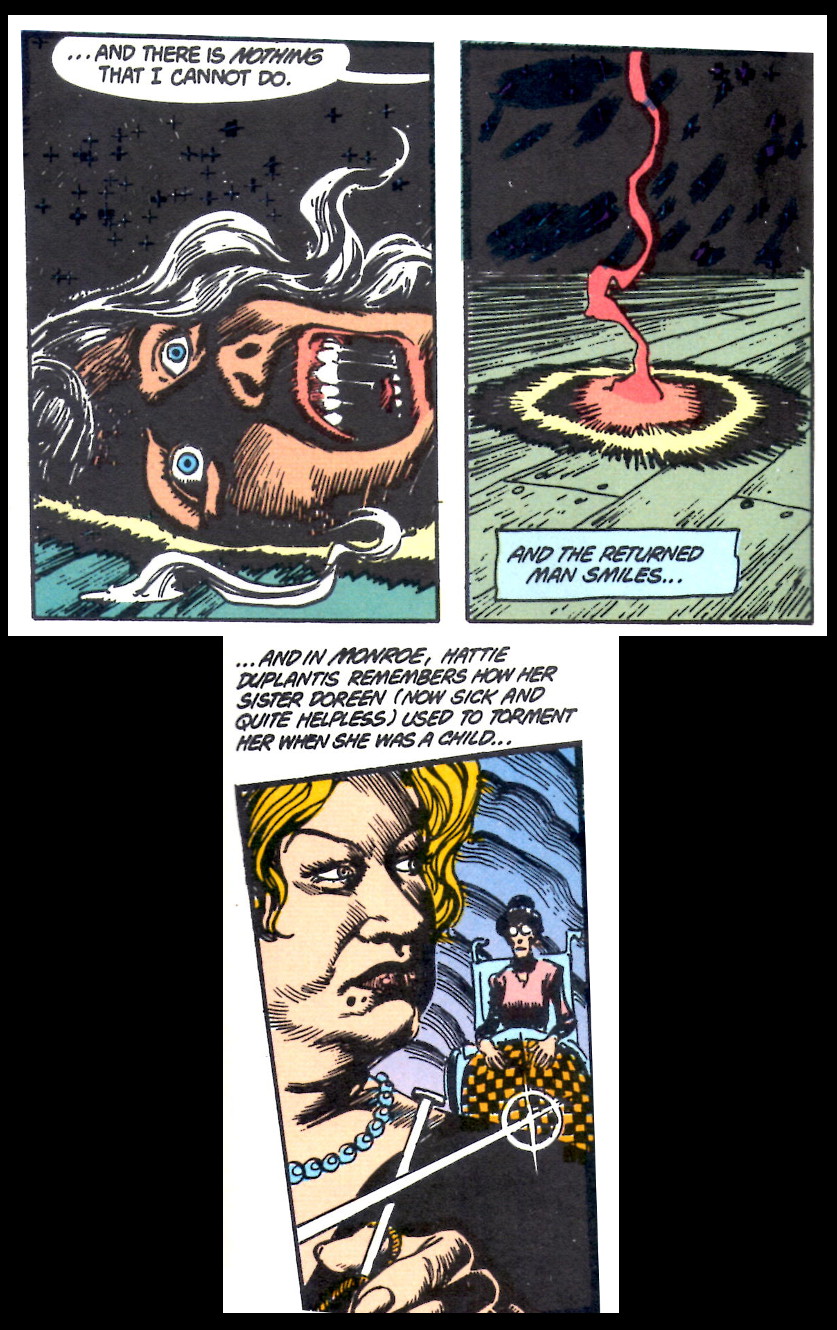

Structure and transition meet in Issue #30, where the gimmick is also the transition. In this issue, a denizen of hell has escaped and returned to plague the living. Whenever this “returned man” smiles or chuckles or whatever, somewhere in the world someone commits evil and madness. The clause “the returned man smiles…” and the following “… and…” provide transitions and structure for the majority of that issue.

Finally, one of my personal favorites is the almost humorous juxtaposition of the word “lines” in the transition between pages 16 and 17 of Issue #41

Pacing and Flow

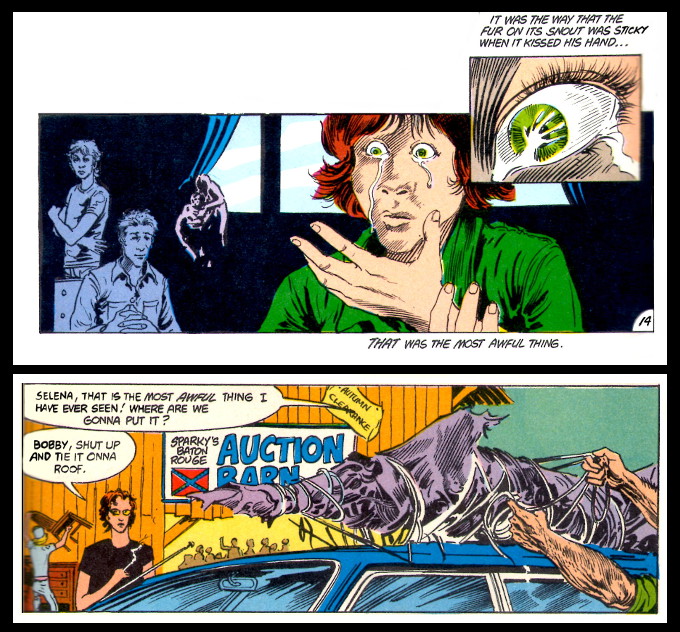

Since Moore is writing a horror/suspense story in Swamp Thing, setting atmosphere and mood is essential. This is done predominantly by slowing the pace of the stories down and focusing on the sensations or psychological implications of the events. Often, a deliberate pacing is achieved by interleaving stories about ‘the inside’ and ‘the outside’. The inside shows the internal mental state of the character, often in confusion or madness, and its inclusion allows for a slow build-up in tension without ‘filler’.

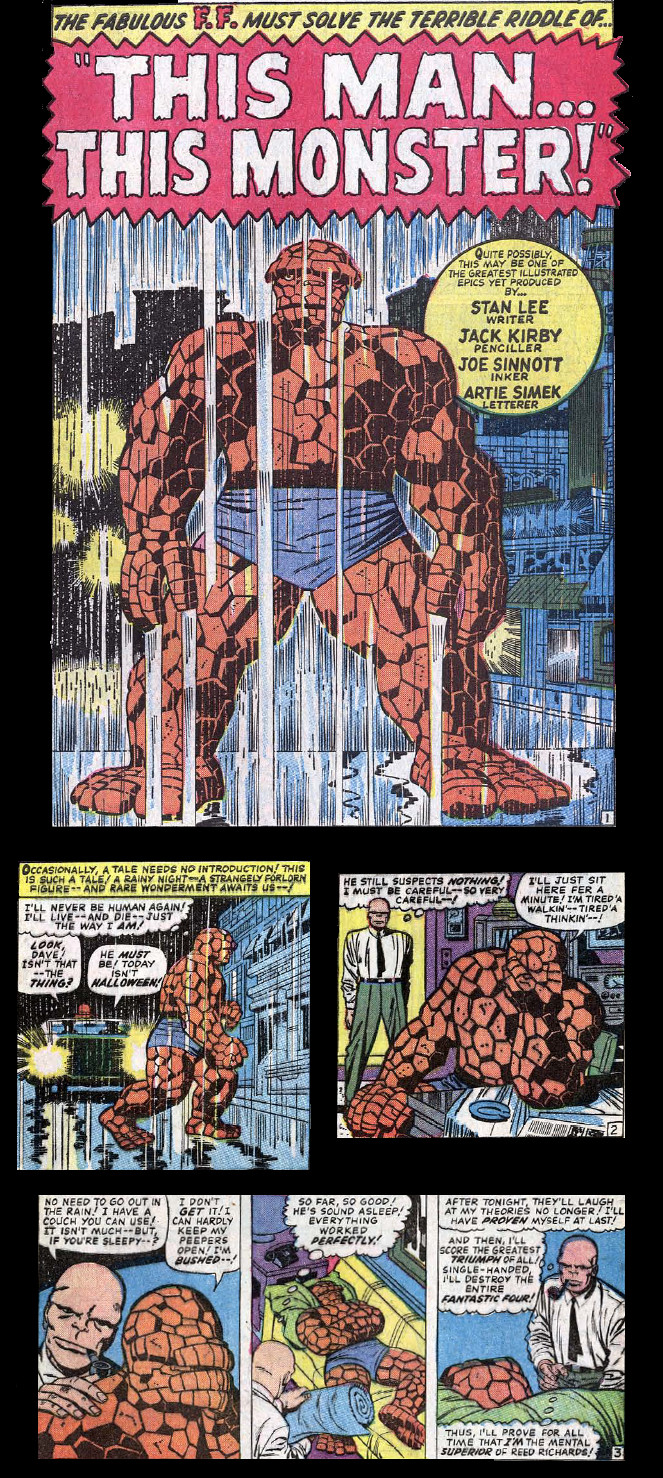

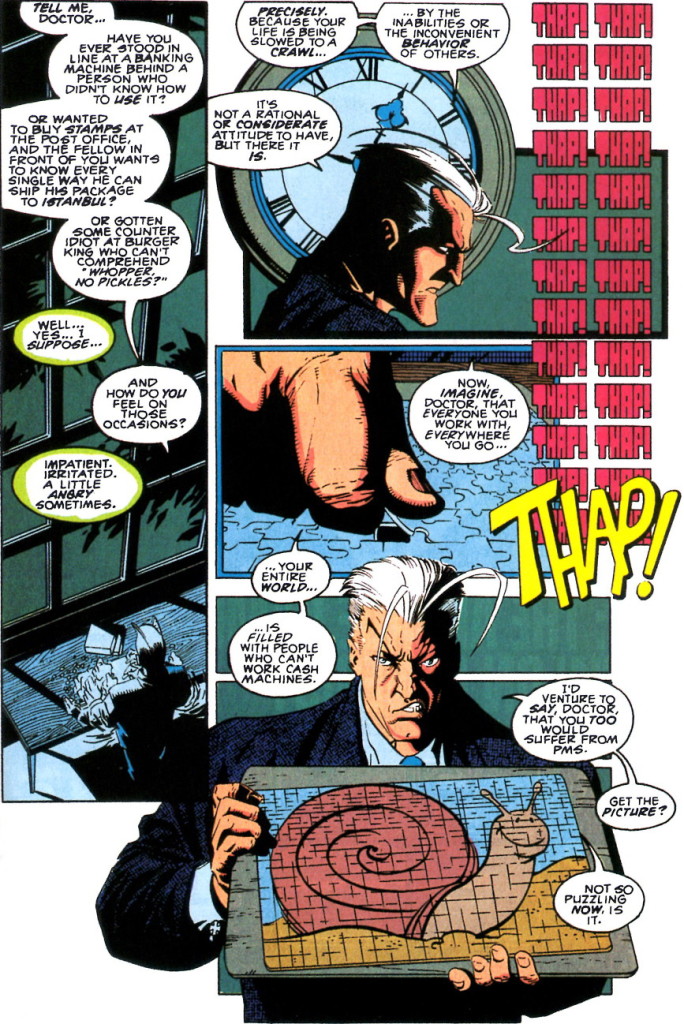

It also allows for more bizarre scenes with a dark humor that adds to the creepiness rather than detracts from it the way conventional comedy would. An example from Issue #22 is the internal madness the Swamp Thing endures after he discovers that he has been living a lie by thinking he was a human transformed into a monster.

Note the word play of “planarian” and “plain Aryan” and the reoccurring theme of eating.

Sometimes, Moore and company do need some filler to round out the page count. Even in these cases, they manage to use it to good effect as in the very bizarre and horrific accident that ends the life of an insurance salesman when he is impaled by a sword fish. This sub-story fills 3-4 pages of Issue #25 and offers again some black comedy that serves to heighten the horror. It also provides a very nice transition (pages 14 & 15)

Plot

As discussed last week, Moore claims that the plot is often the least important piece. But is that claim really true in practice rather than just in theory? I believe the answer to be yes. As a horror/suspense writer Moore’s predominant interest is in setting mood. As a result, what happens is not nearly as important to him as how the characters feel about it.

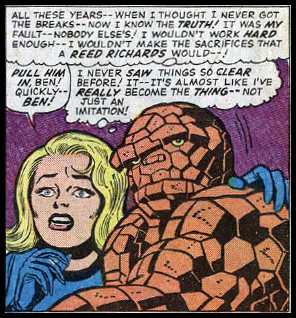

As a very clear example, consider the content of Issue #28, entitled “The Burial!”. The whole issue is devoted to the Swamp Thing coming to peace with the fact that he is not Alec Holland. The plot of the entire issue can be summarized in one sentence: Swamp Thing digs a grave for Alec Holland, finds Holland’s remains, puts them to rest in the ground, and comes to peace with his existence.

Moore chooses the elliptical story structure here, starting with an empty grave

and ending with burial mound and the resulting peace.

The above 4 panels constitute a small fraction of the 135 panels found in the issue. The remainder of the space is spent on finding Hollands remains both physical and psychological and how the Swamp Thing reacts to this.

Many of the other issues fare similarly and it is reasonable to regard Moore as being more in line with Poe or Lovecraft in his approach to storytelling. His focus is almost always on the characters and not on the events surrounding them.

Conclusion

Having toured Alan Moore’s work for the past 3 weeks, what to make of it? I think there is no denying that Moore is talented and that he is a consummate professional in his craft.

He clearly has mastered some basic, compelling approaches to sequential art and uses them to great effect, with frequent innovative variations on these techniques. However, I can’t escape the feeling that there is a sort of glamour, in the traditional fairy sense, about his work; that style exceeds substance and that impressions and feelings dominate events. In real life, events matter, results are important, and talk is cheap. While I admire his work, I judge that much of his storytelling is more like a dream. Once the sleeper awakens the particulars fade but the feelings remain.