The Wicked and The Divine

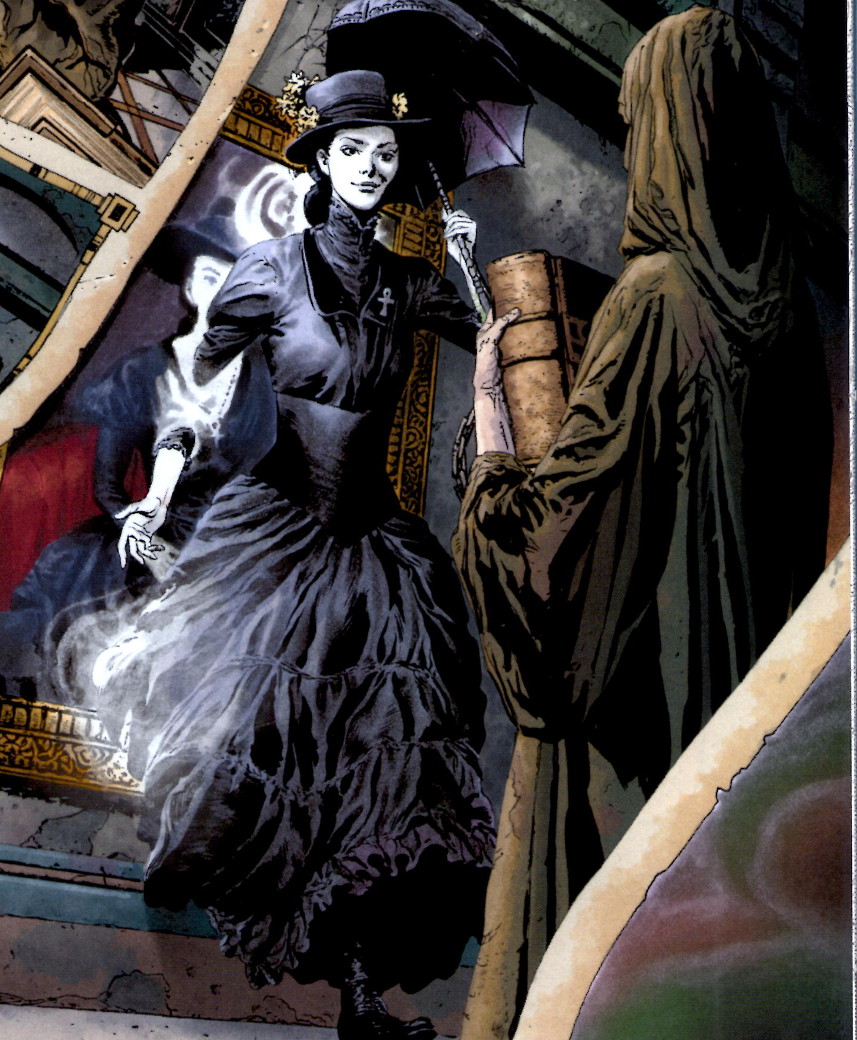

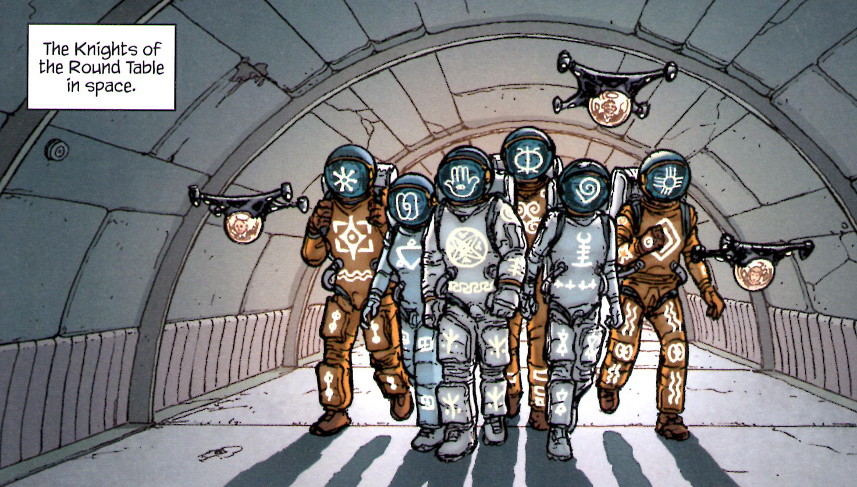

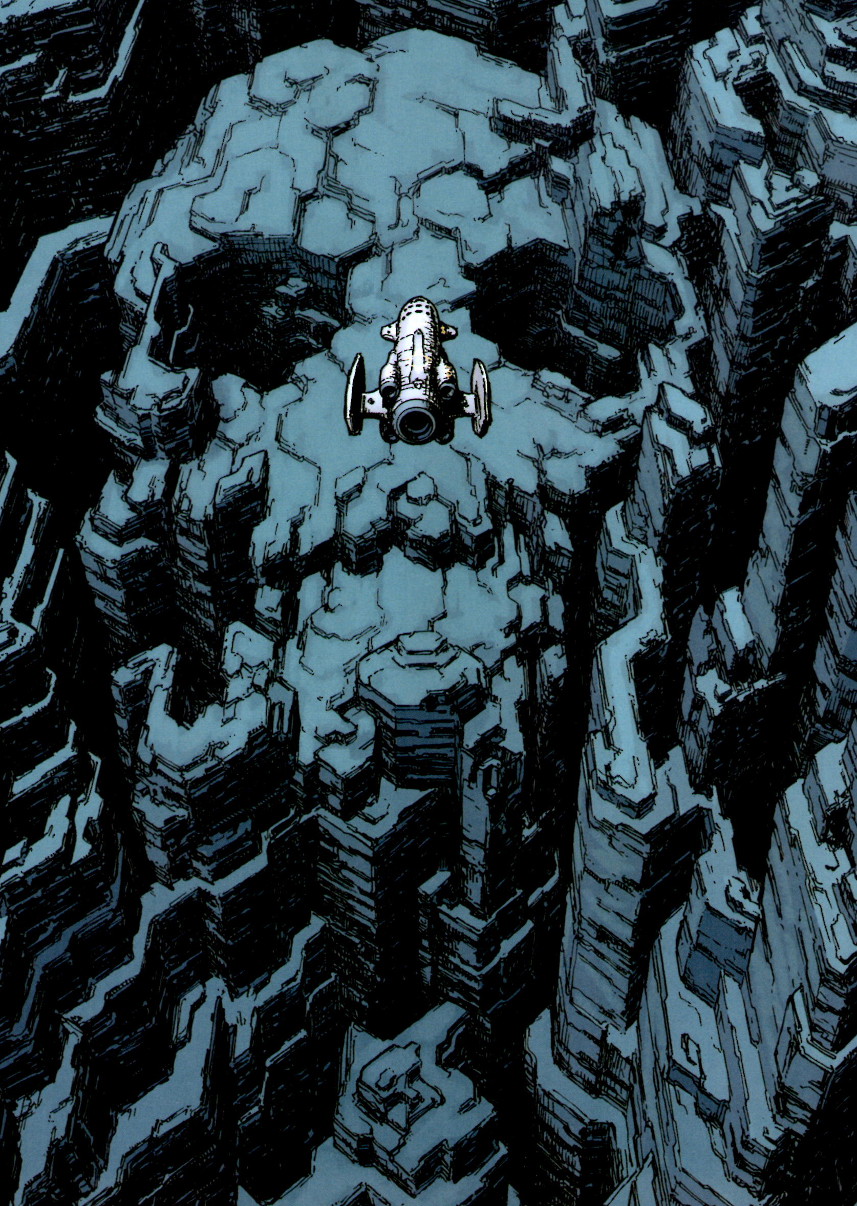

The Wicked and The Divine is an ongoing series from the creative team of Gillen McKelvie (writer) and Wilson Cowles (main artist), published by Image Comics. The basic theme of the comic is to examine the question ‘what price fame’ and the basic mechanism for performing this evaluation is that the most visible pop icons are literally gods – 12 paranormal beings with names plucked from every belief system on the planet (although not all 12 need be present at the same time – their emergence being staggered).

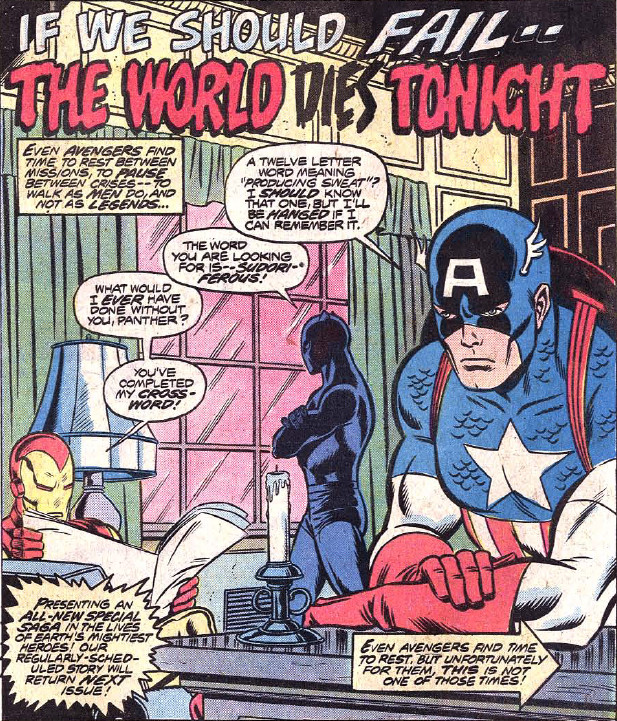

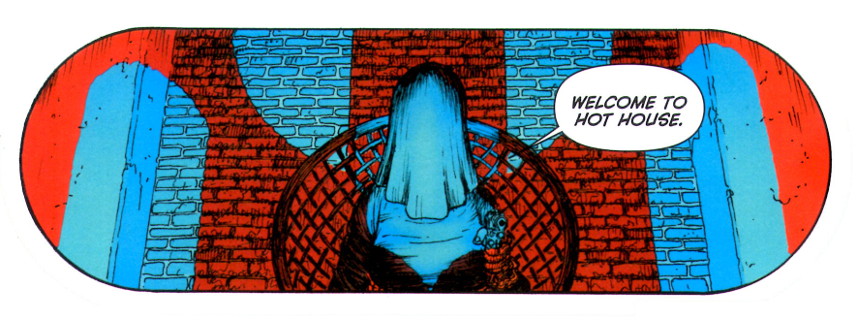

However, there are rules and a catch. The rules are few but important. These twelve gods are part of The Pantheon which promotes them as pop stars, affords them access and privilege, handles their fan interactions, and cleans up after their ‘miracles’, all at the expense of subjecting them to the oversight of a mysterious, masked old woman. The catch is based on the old saw that says that a candle that burns brightest burns for the shortest time. Two years is all you get as a god before you die.

At the time of this writing, the creative team has completed 3 major story arcs and, truth to tell, I am still unsure as to how I feel about the effort. In order to understand my ambivalence, I need to sketch not only the events that have been revealed in the text but my own inferences based on them.

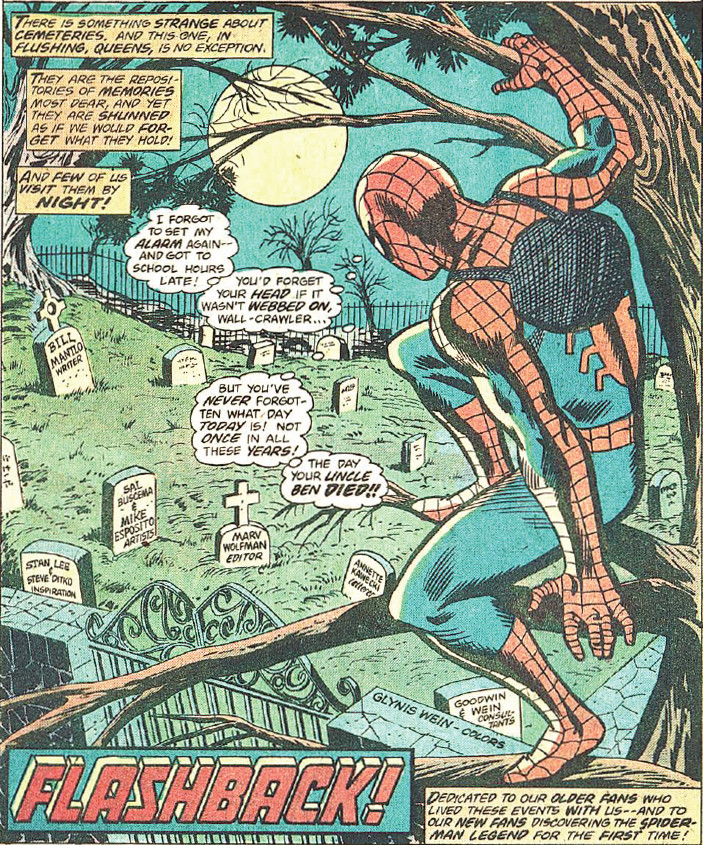

The method of storytelling is predominantly sequential with flashbacks thrown in at various junctures to fill in a bit of characterization or to answer an open question. There are at least twenty important characters but most of them seem to be of the same essential temperament – greedy, petty, and generally unsympathetic. The major distinction between them is how they approach the fame associated with being super-powered gods/pop stars. These characters fall into three groups: the famous, the wannabes, and the enablers. There seems to be no considerations of other types like, say, a character who shuns fame because he truly knows the difference between the good life versus the high life.

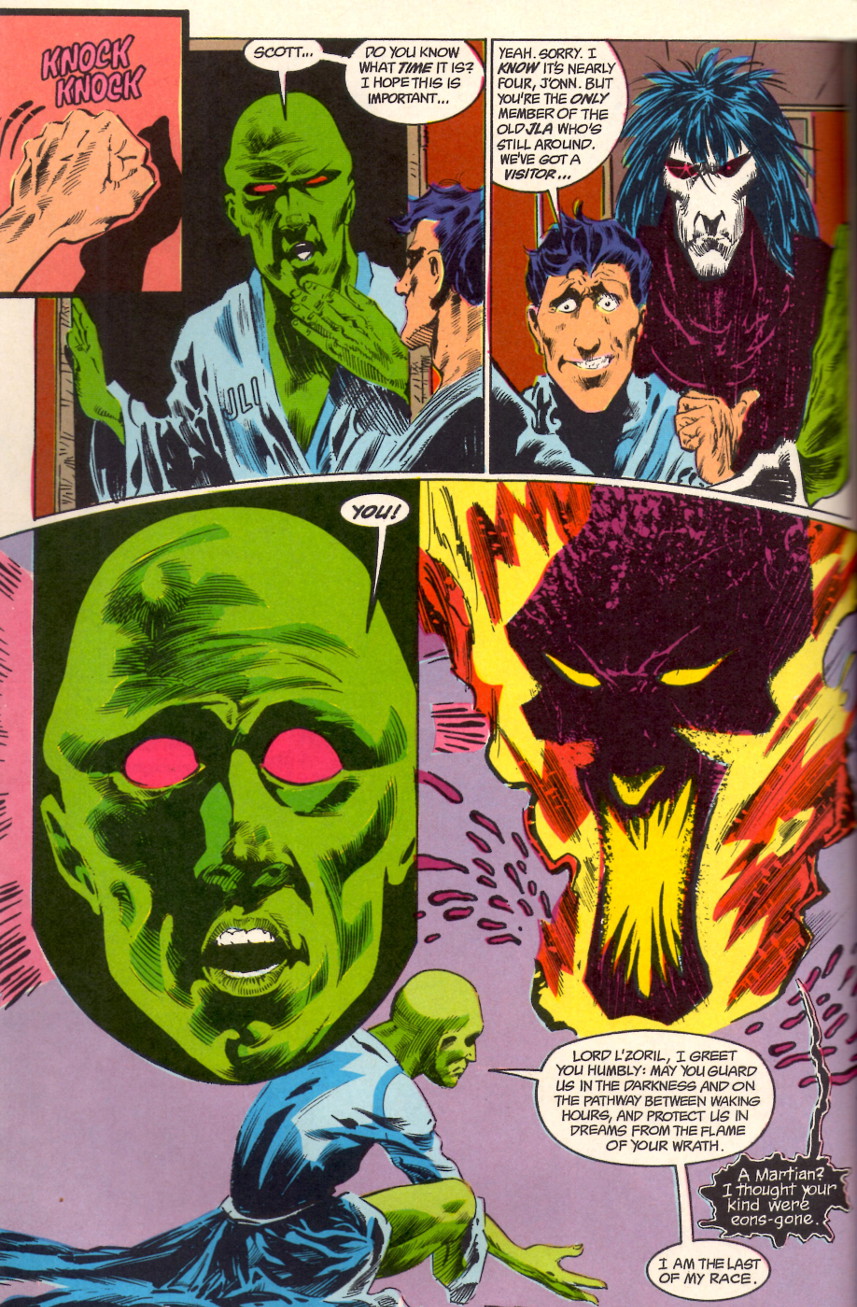

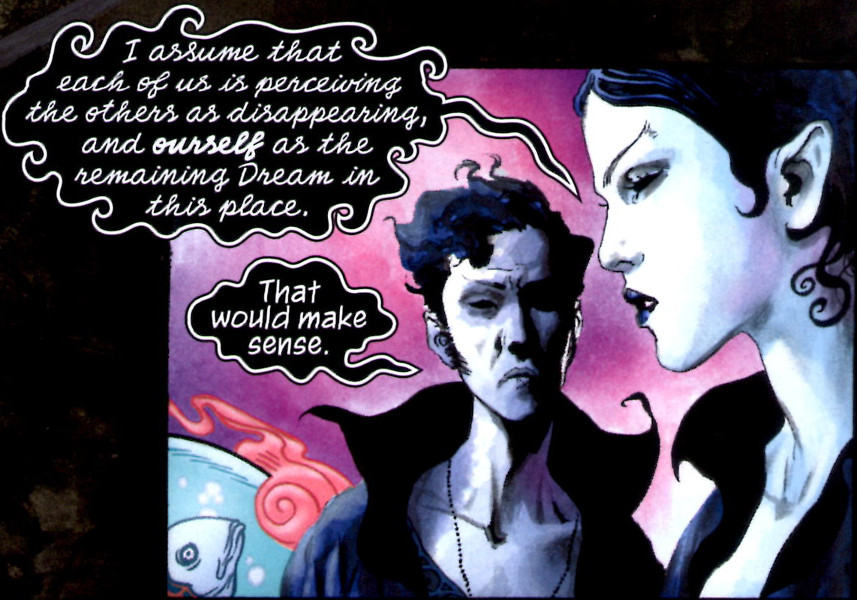

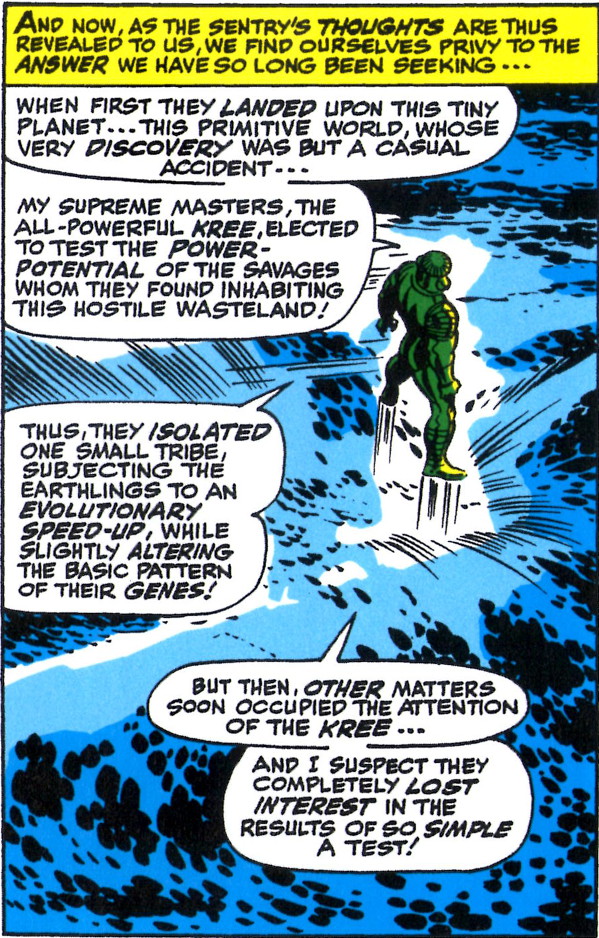

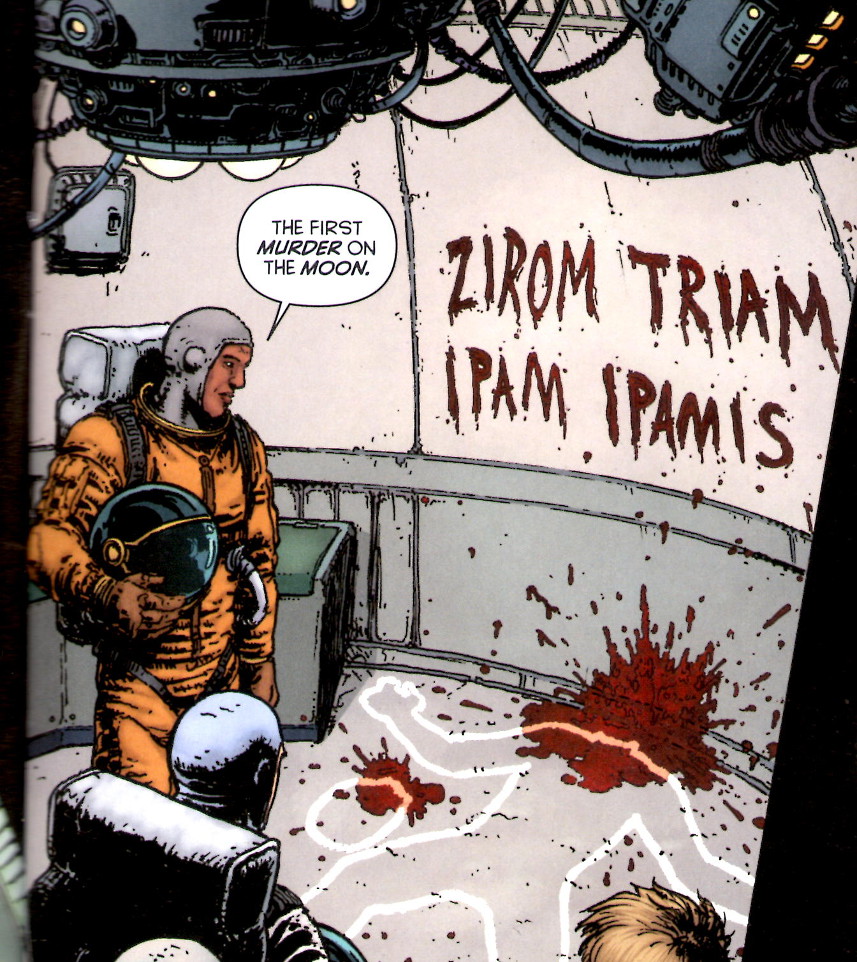

The plot is actually quite simple at its core, although the creative team does a nice job of decorating the events with enough flesh that the skeleton doesn’t peek out much. The events of the story start tantalizingly enough about 90 years earlier with a previous recurrence (such is the name given to the cyclic return of the gods). While twelve gods comprise a recurrence, at the opening scene we see only four of them at their gathering table. The remaining spots are manned with the skulls of their deceased comrades.

The older woman, dressed something like a middle-aged flapper sporting a mask,

addresses them with some final words before stepping outside the house which then proceeds to explode. So much for the gods of the 1920s!

The scene moves forward nearly a century to the next recurrence and our attention is now focused on perhaps The Pantheon’s biggest fangirl, Laura Wilson, who skips classes at her local university in order to be caught up in the excitement that is The Pantheon.

Laura distinguishes herself in the eyes of The Pantheon by being the last person to pass out due to excessive ecstasy during a concert performance by Amaterasu (Japanese sun god). Waking up after her swoon, she becomes acquainted with Lucifer and, in typical Faustian fashion, promises to ‘do anything’ for a chance at meeting with other members of The Pantheon.

Whether this little slip amounts to anything remains to be seen but why have a Lucifer in the story to begin with if rebellion, soul-selling, and quibbling about terms isn’t needed. In any event, the L’s go off to a Pantheon post-performance party. The fun barely gets going, when two gunmen, shooting from a rooftop across the street, open fire on the intimate little gathering, provoking Lucifer’s ire. In due course, the assailants collect what they have coming when Lucifer steps out onto the balcony, snaps her fingers, and proceeds to vaporize their heads.

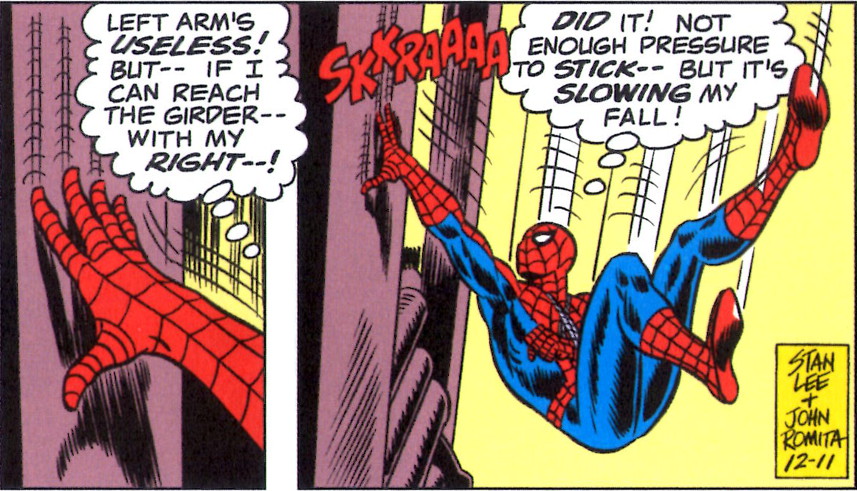

A short time later, the jurisprudence system has convened in a court room to decide whether the blond-haired hellion is guilty of murder. In a characteristic act of defiance, Lucifer taunts the judge, asking how anyone could kill another by simply by snapping his fingers like so. Unfortunately, Lucifer’s snarky speech is cut short when, at the moment she snaps her fingers, the judge’s head also explodes. Lucifer, as shocked as anyone, realizes she’s in real trouble now and, as she is being led out of the courtroom past Amaterasu, she whispers a request for Amaterasu to get Ananke to help.

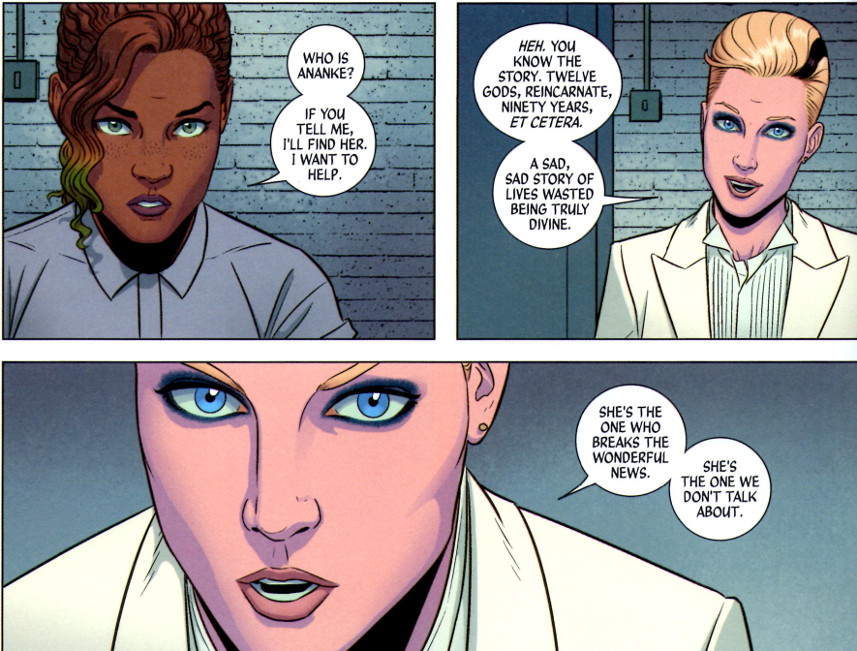

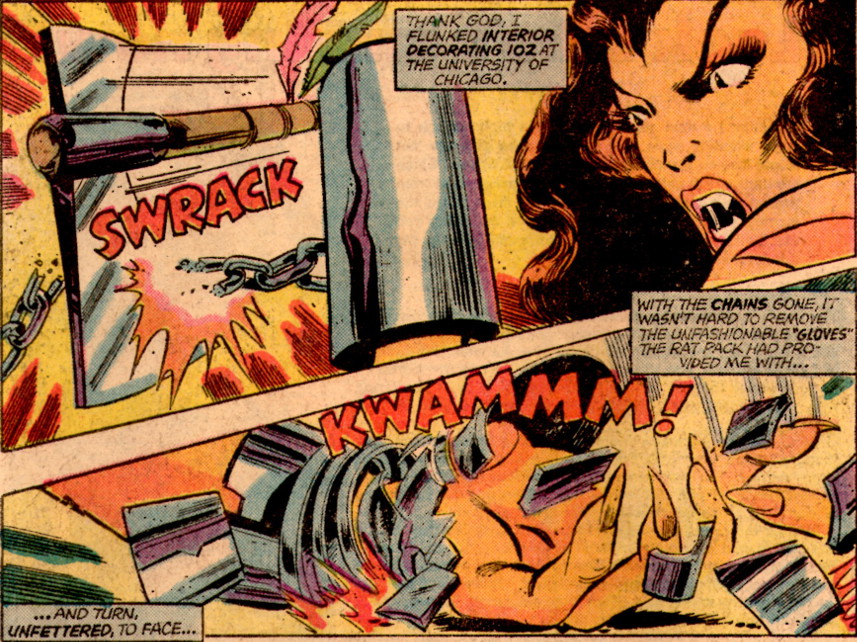

Despite her protestations that she didn’t kill the judge, the public at large concludes Lucifer is guilty. And off she goes to prison. Sitting in a cell and sporting finger cuffs that prevent more snaps, Lucifer remarks dourly on the fact that her only visitor is Laura. Still beggars can’t be choosers, and Laura manages to get the Lord of Lies to open up to her. Plucking up her courage, Laura asks about the whispered name of Ananke that she had overheard in the courtroom. Lucifer curtly responds with an answer that would find more a home in Harry Potter.

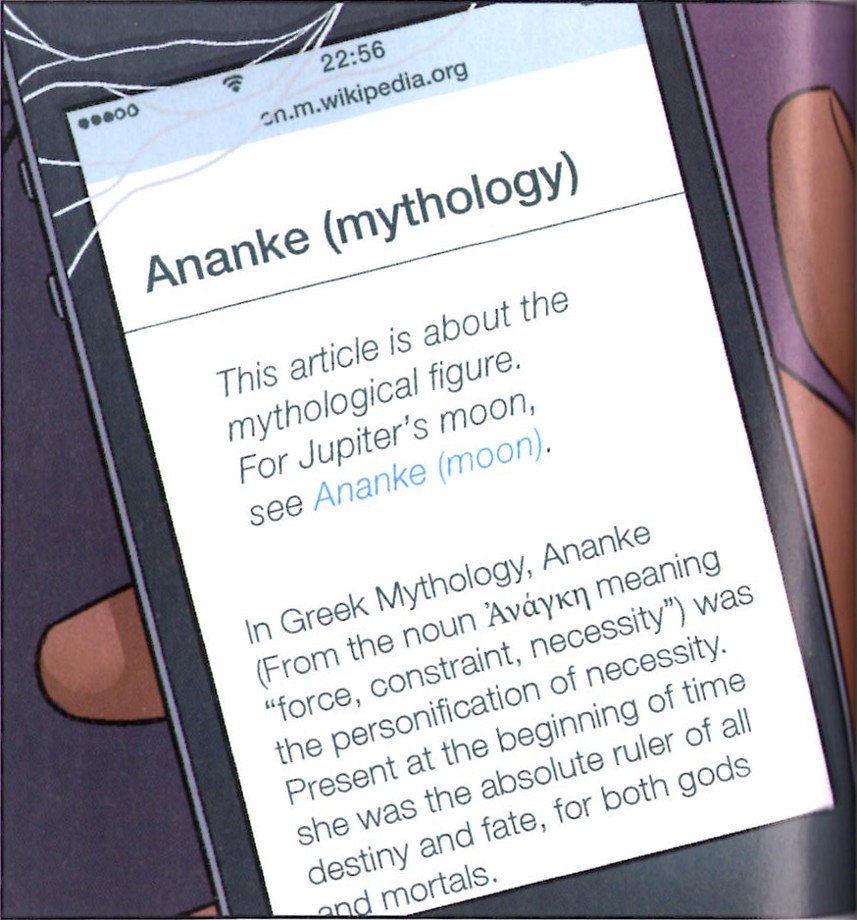

Not to be deterred and intrigued by a member of The Pantheon who is outside of the limelight, Laura turns to her phone and to Wikipedia to find out all.

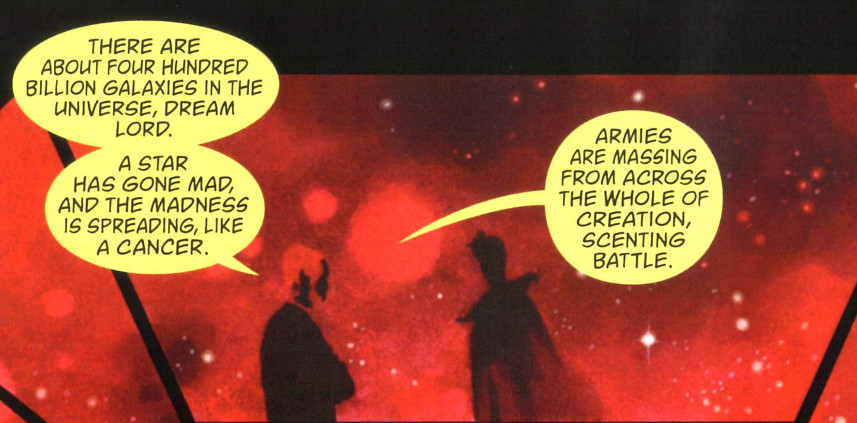

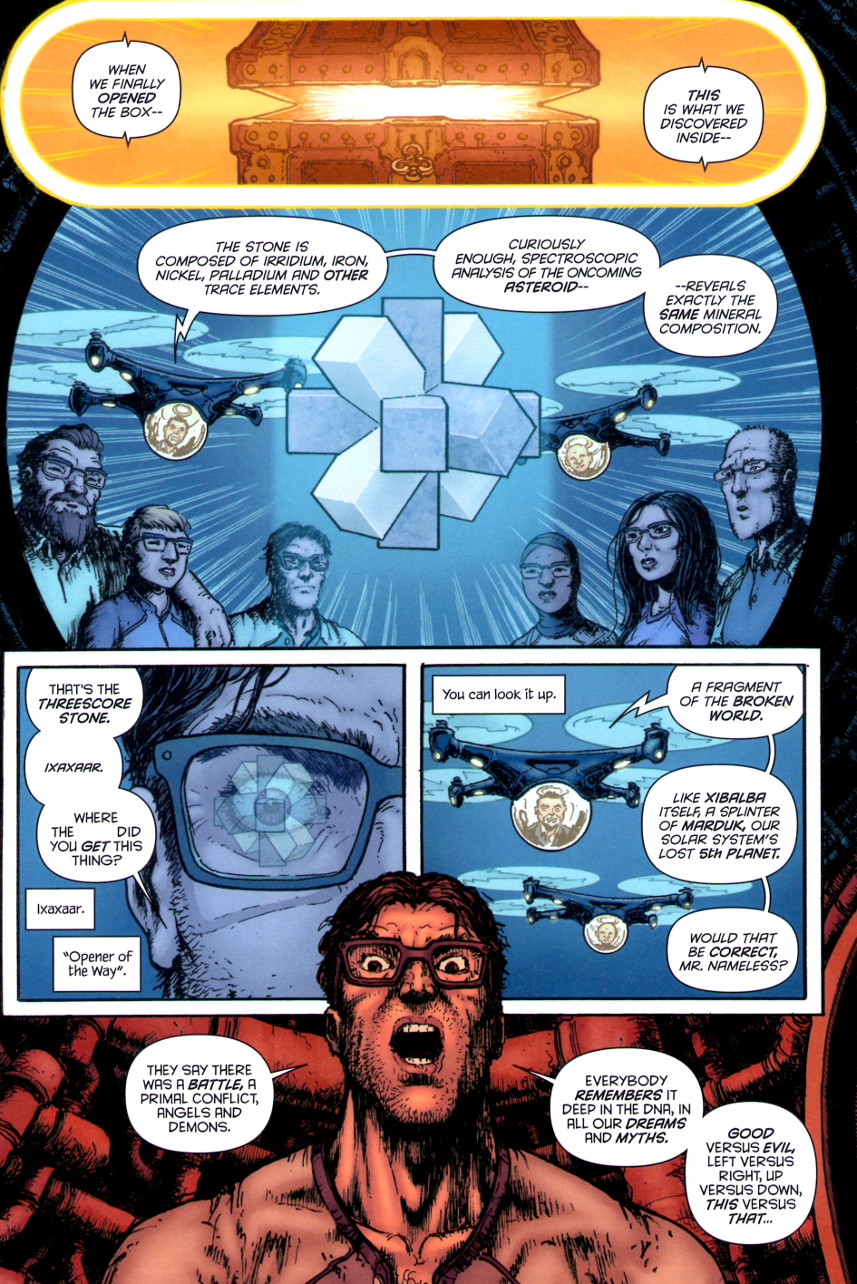

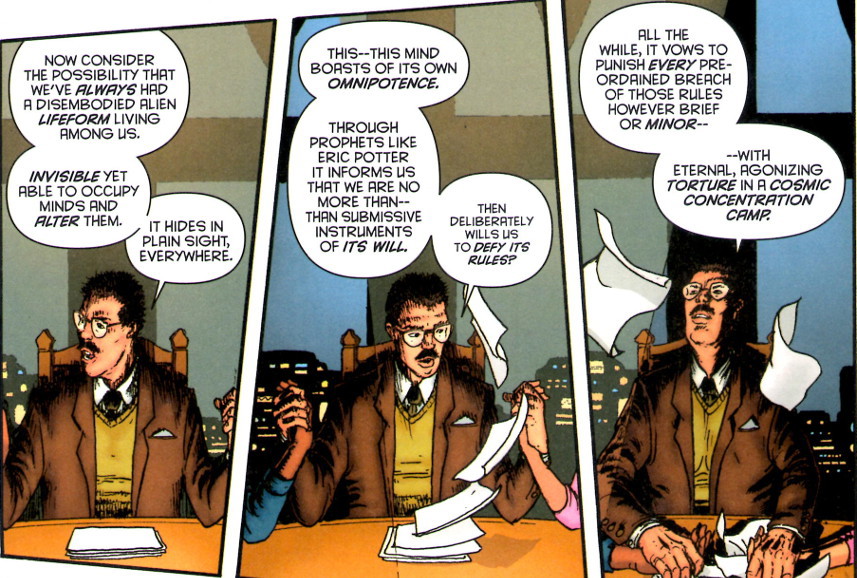

Meanwhile, back Valhalla the headquarters of The Pantheon (yes that means there is an Odin), the reader is treated to just what Ananke’s position is as she expresses herself to the other members of the Pantheon.

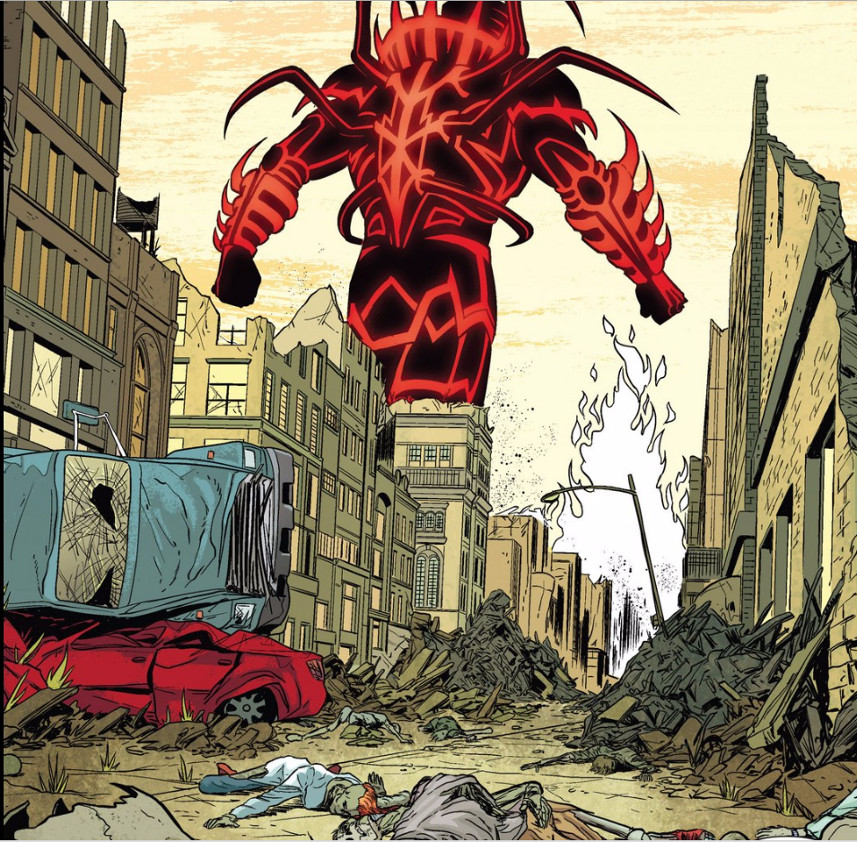

While her last words about the recurrence and human inspiration are cryptic at this point in the story, their meaning becomes clear much later on when Ananke explains that the reason for the god’s return every 90 years is so that they can combat the darkness and secure a better future for humanity. I suppose this is the writer’s way of explaining the various golden ages that have cropped up in human history and then collapsed and disappeared. Ananke also explains her role. As goddess of necessity, she is tasked with sheepherding the new incarnations of the gods, who emerge from the general population at the appointed time but with no awareness of their previous incarnations. She is the only one who persists from recurrence to recurrence.

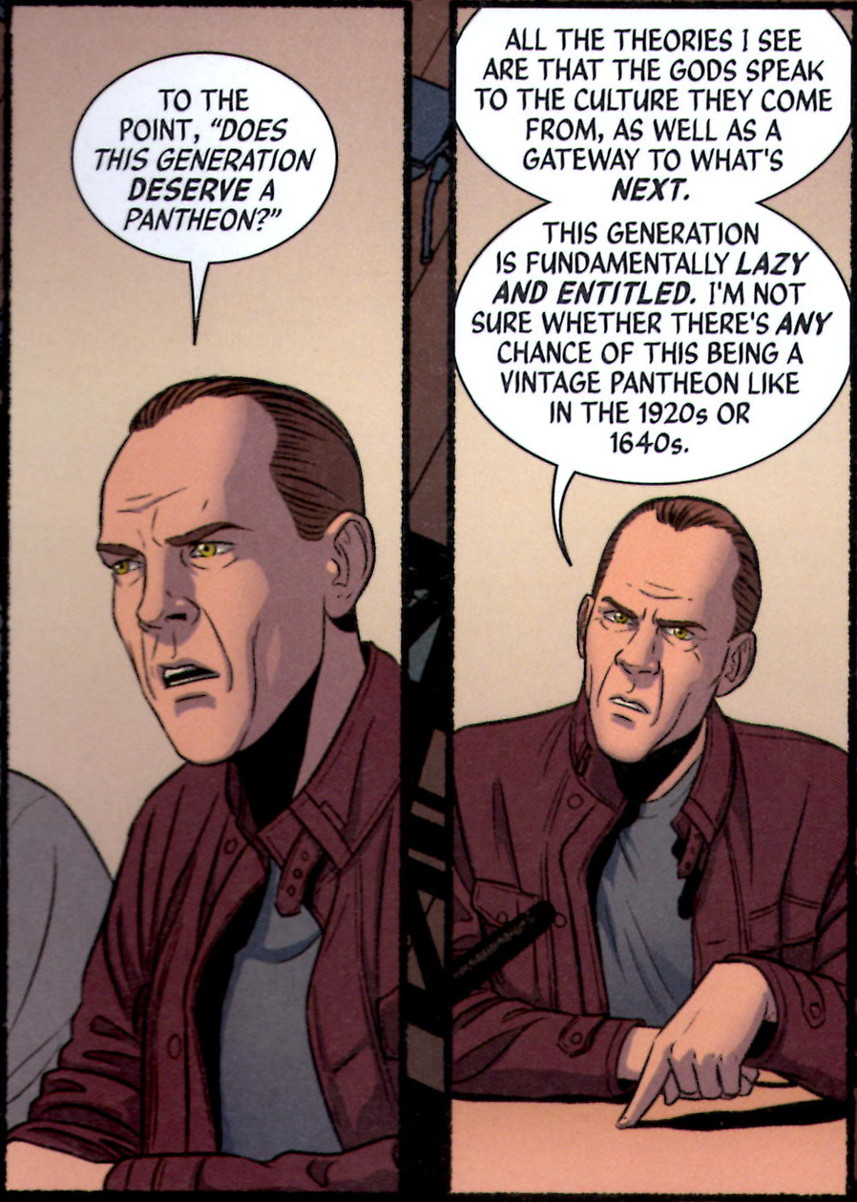

The public clearly have bought into the beneficial aspect of the recurrence, with some members even asking

This recurrence myth may be a reasonable explanation for the characters in the story, but the reader is purposefully left with a sense that much of this ‘truth’ is simply Ananke’s propaganda, which she uses to cover more sinister machinations.

This last point is further emphasized by the single central event of the story. Lucifer, left to rot in prison with no attention from Ananke, predictably breaks free and spreads chaos everywhere. Claiming she has no choice, Ananke ends Lucifer exactly the way the gunmen and the judge do; by vaporizing Lucifer’s head.

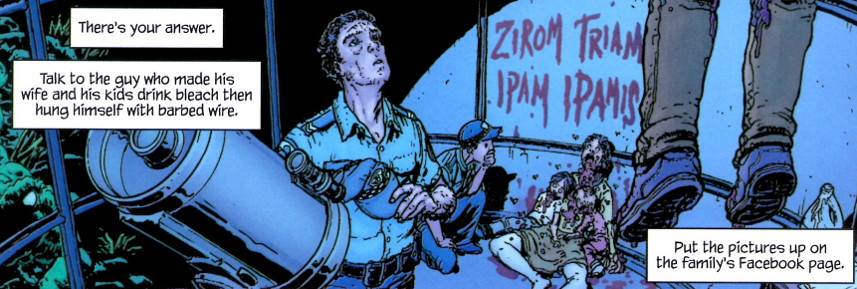

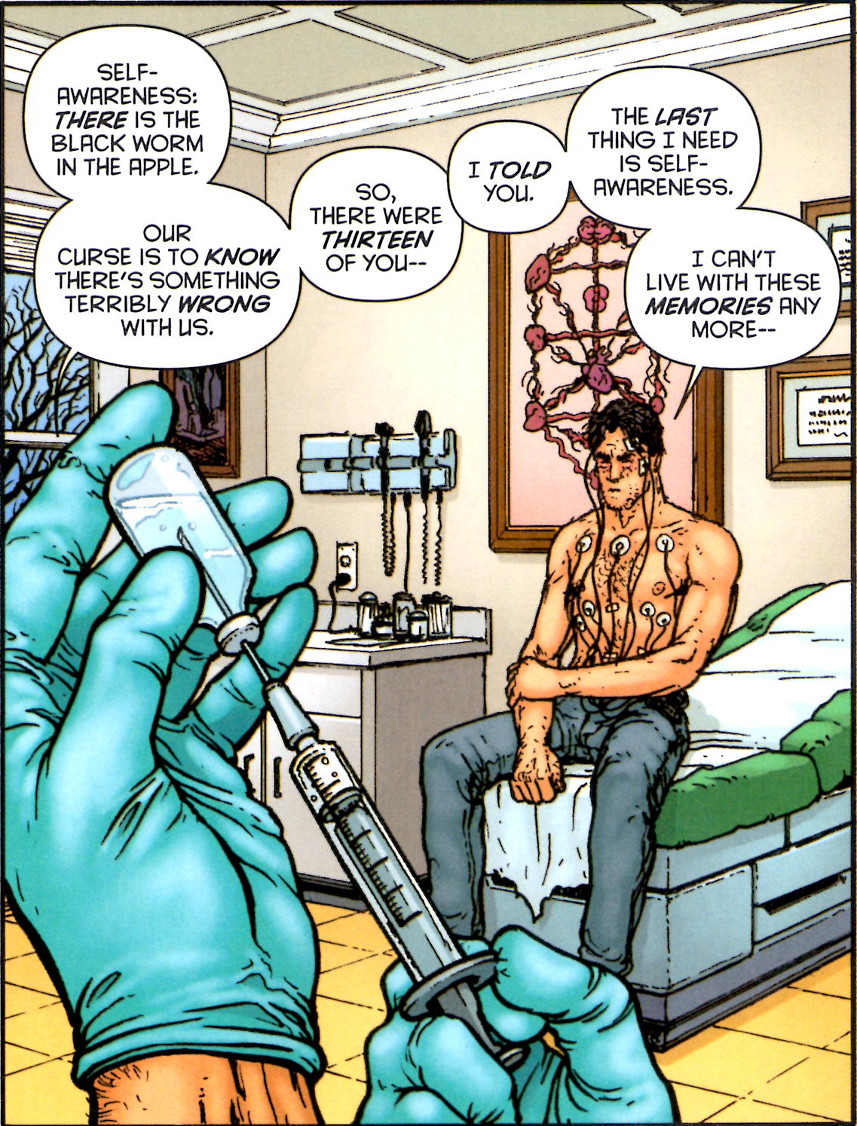

And so begins the second arc, a motive-driven, whodunit investigation instigated by Laura, who is aided by an investigative journalist named Cassandra. Their aim is to discover who really killed the judge, framed Lucifer for the death, and thus brought about her end.

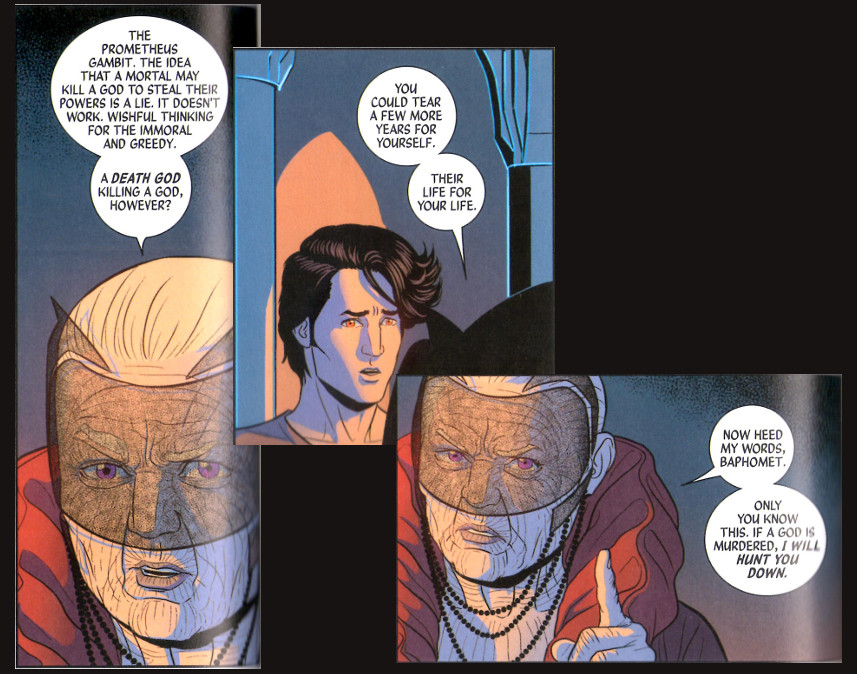

At first their investigation is productive. They quickly find evidence that points towards the notion that the gunmen’s motive was the Prometheus gambit, which is a way for a mortal to steal a god’s power by assassinating the god. They also witness the arrival of a new Pantheon member – Dionysus. Unfortunately, they are not privy (unlike the reader) to the Ananke’s manipulation of the death god Baphomet,

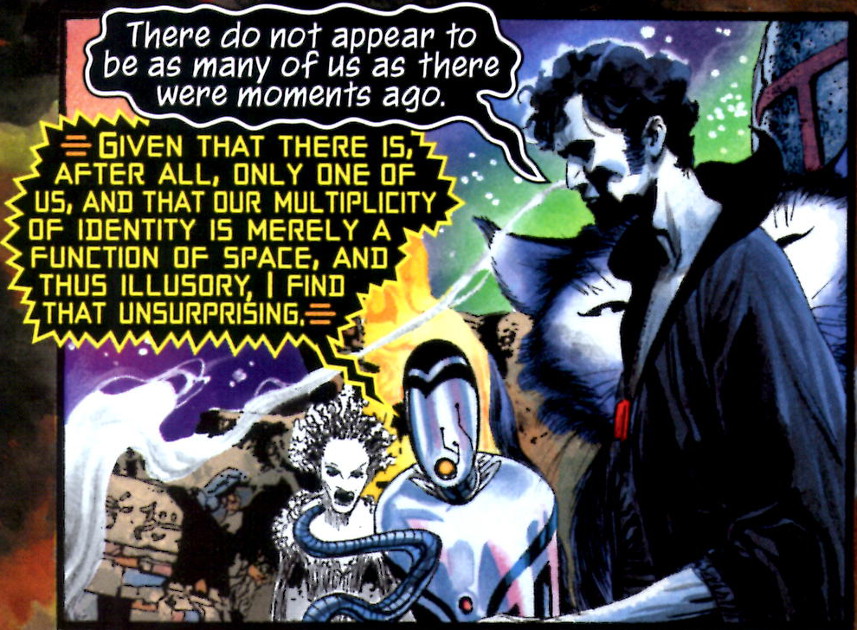

which sets the death god at odds with the rest of The Pantheon. All hope of Laura and Cassandra discovering this ploy is dashed when Ananke declares Cassandra (and her two assistants) to the be the last member of the recurrence – the Norns.

Laura can’t help feel disappointed that she wasn’t chosen/revealed. However, soon afterwards, Ananke declares Laura to be Persephone.

Immediately after, Ananke kills Persephone and her parents. Heavy is the price of fame, of finding you are special.

At this point, it becomes clear that Ananke is manipulating the Pantheon to kill each other to fulfill her own ends. These haven’t been revealed but no doubt her motive is either jealousy (she’s forced to live perpetually in the shadows as an old crone while the rest cavort in the public eye) or gain (she’s stealing their life force to gather power or perpetuate her own existence – it’s not clear whether there have been repeating gods in the recurrence).

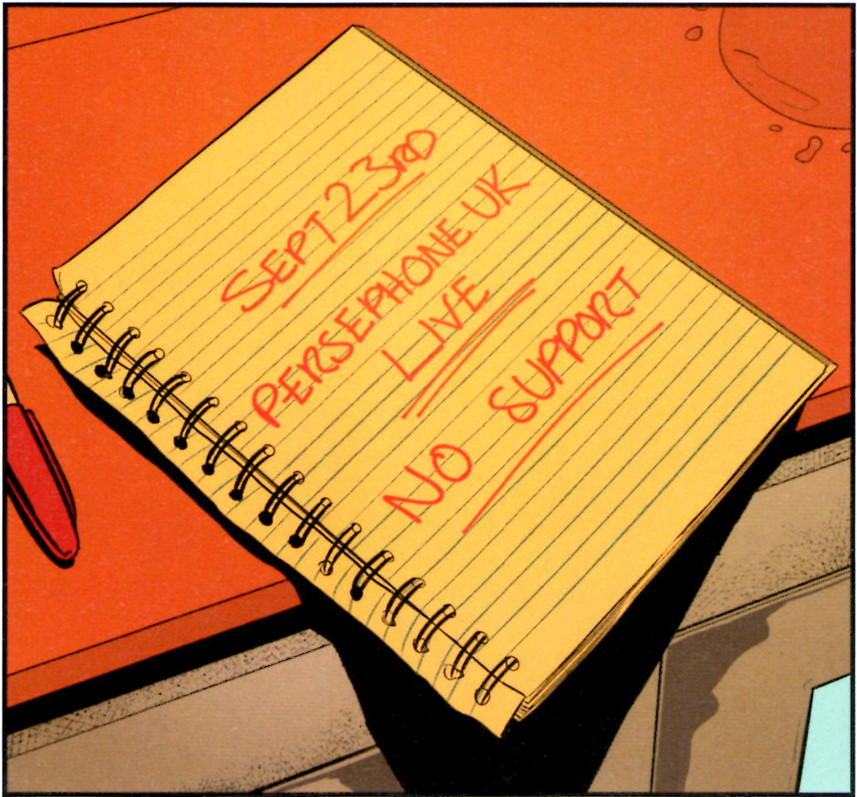

The third story arc supports this conclusion as it is definitively revealed that Ananke is the party responsible for the judge’s untimely death and that Odin is an accessory after the fact. It is also a reasonably supported conclusion that we haven’t seen the last of Laura. After all, in the classic Greek myths, Persephone returns from the underworld. Foreshadowing of this outcome is found at the end of the current issue (#17) where a Pantheon act is booked for performance and the headliner is

I suspect that the coming issues will feature Laura/Persephone’s return from the dead, the revelation of Ananke’s manipulations and schemes, a dramatic confrontation between the two, and a final resolution in which the gods are either able to exercise free will or where the recurrence is permanently broken and the gods are no more. And therein sits the problem. I’m pretty sure I can see what’s coming, and it’s all so predictable and tedious. In the end I fear that the story will be neither wicked nor divine but simply banal. Oh, well; time will tell and, hopefully, sooner than 90 years from now.

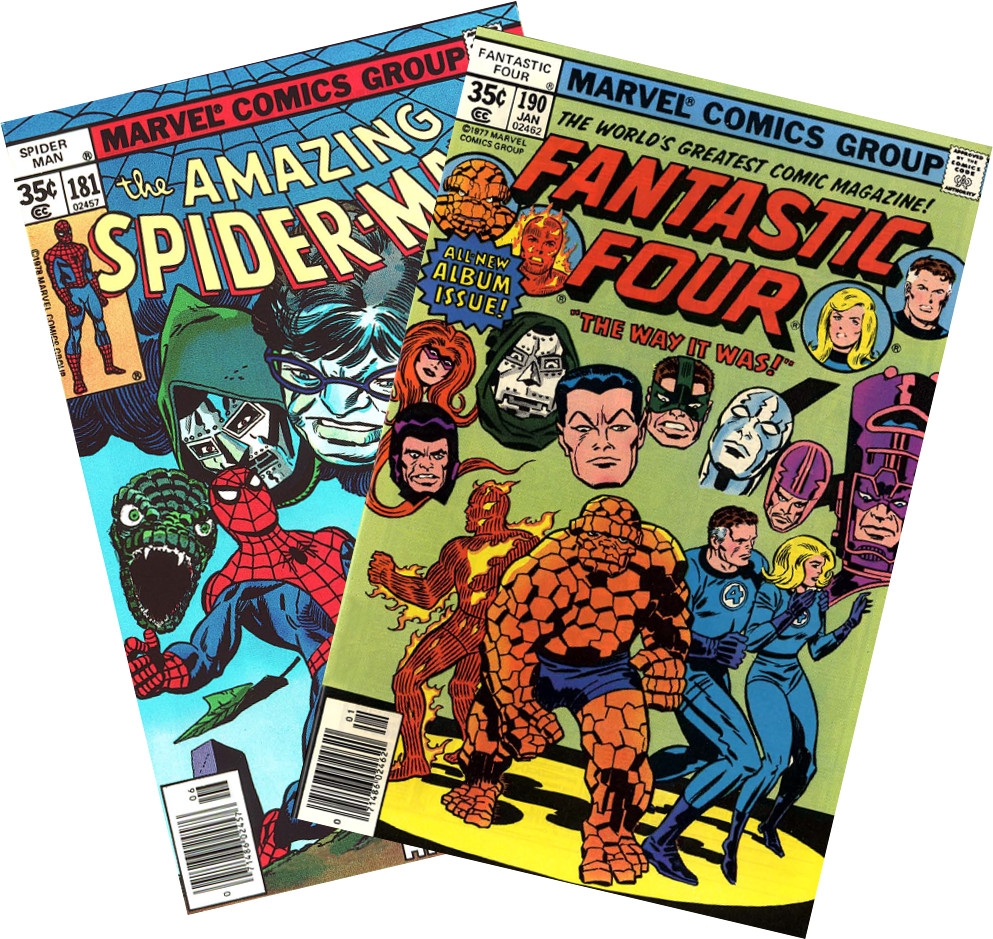

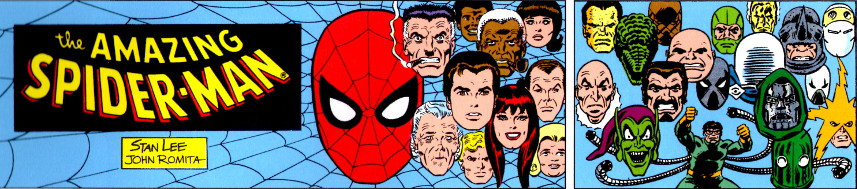

Added bonus: The complete 12-god wheel from the series is:

This composite image is not available in the series itself. The gods in the modern recurrence are (starting at the top and going clockwise): Amaterasu, Lucifer, Sakmet, Baphomet, Minerva, Odin, The Morrigan, Dionysus, Inanna, Tara, Baal, and the Norns.