Well it’s over. It’s been a few months now since Marvel’s company-wide, total reboot of their creative universe has drawn to a close with the last installment of Secret Wars #9. I thought it was a good time to pause, survey the new landscape, and reflect on how we got here. Over these next four installments, I’ll be analyzing just what Jonathan Hickman, the writer and creative glue, tried to do, what the high points and the lows were, and whether or not it really came off as expected.

In this article, I want to set the stage for Hickman’s undertaking by giving an overview of what he tried to implement and the creative and commercial tensions under which he operated. In a nutshell, Hickman attempted what could only be called comics first, true foray into the epic. This may seem a strange thing to say since ret-cons and reboots have been fairly common on the comics scene for several decades now and mega-crossover events are nearly as common. But I stand by this assessment since an epic is not and should not be judged solely by how large it is. It is true that size and scope are crucial elements, but an epic must, simultaneously, also deal with the big questions in both big and small ways. Hickman’s work on what I will call the Everything Dies storyline (the reason for which I give below) meets both criteria, albeit not always successfully.

The question of size and scope is the easiest one to understand and support, so let’s discuss this one first. The scope of Everything Dies was unprecedented in the comics industry. To appreciate that claim, consider that the first of these continuity cleanups, DC’s The Crisis on Infinite Earths, was a 12-issue limited series with important links to the existing titles but with a storyline comprehensible and digestible as a standalone event. Subsequent reboots of the big two have grown even more and more complex and more cosmological with dimensions, universes, and multiverses being taken apart and put back together within most if not all of the current series, but the size and scope has always been limited to at most a year of crossover events. What Marvel did in the Everything Dies storyline literally dwarfs everything that has come before combined.

The core Everything Dies storyline actually starts publication in starts in the winter of 2013 with launch of the twin Avengers publications Avengers and New Avengers. Both of these titles, which were written by Jonathan Hickman and drawn and inked by a host of artist teams, ran for almost 3 full years; spanned 78 issues (plus additional ancillary tales); played host to two separate company-wide crossover events: Infinity and Original Sin (each of which brought even more issues into the fold); and eventually led into the final Secret Wars climax.

Obviously Everything Dies storyline was required to be more than a creative, literary success; it also needed to be a commercially lucrative, since it would set the stage for all future Marvel titles. In addition, although not explicitly stated, it also needed to be done in such a fashion that allowed Marvel to downplay the X-men, Spider-Man, and Fantastic Four franchises since none of these was in the stable of Marvel Studios at the time of the publication. As a result, the core of the tales centered on the Avengers, Inhumans, Black Panther, Doctor Strange, and the Sub-Mariner, with only bit appearances by the X-men and Spider-man. The Fantastic Four are almost completely absent as a ‘brand’ and only Reed and Sue Richards really play a role.

Of the two of these titles, the Avengers title is more action oriented, more classic, and more wholesome. The New Avengers is a darker and, perhaps, more interesting title. At the core of both of them is the ethical dilemma called the Trolley Problem, which asks when is it permissible, or even imperative, to sacrifice some life so that other life may be saved.

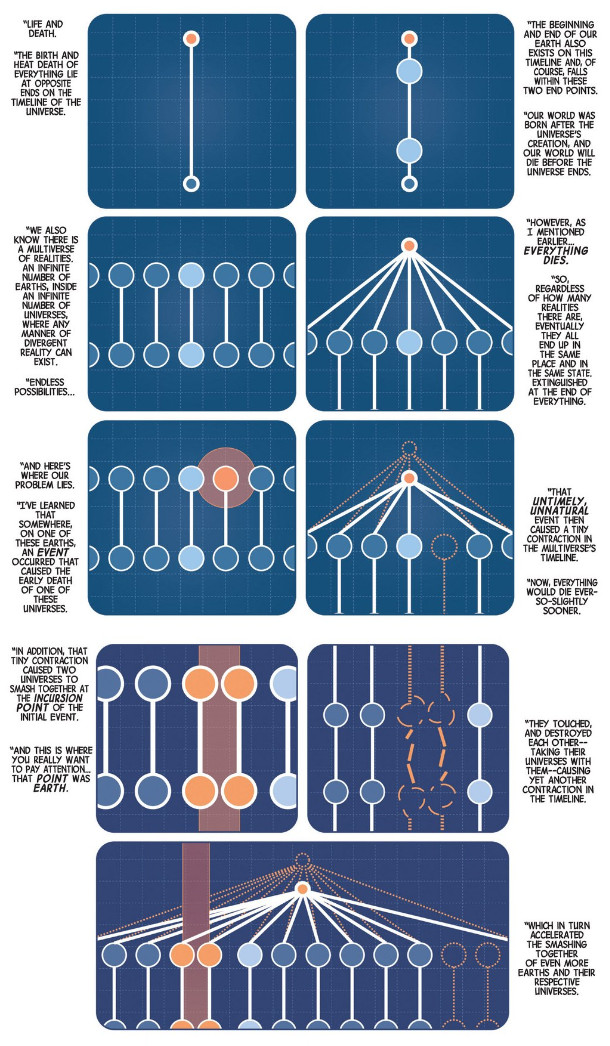

To set the stage for this form of the dilemma, Hickman had to invent a new type of cosmology. The following composite image, pieced together from material taken from the New Avengers, Hickman tries to explain the roots of the quandary.

The pinching together of two universes happens along the specific timelines (worldlines in the technical jargon) of their respective Earths. Left unchecked, such an incursion destroys both universes. However, if there were a way to destroy one of the Earths, the both universes would survive as another discussion of the multiversal fate informs us

On the surface this may seem to be no different than the continuity cleanups but the Trolley Problem aspect, which is now so large as to engulf the entire published output of Marvel comics, provides a nuance not in the earlier reboots. It is no longer a good versus evil race-against-time, but an authentic situation wherein men of good conscience can view the same set of facts from different points-of-view and take widely different actions, as a result.

Of all the infinite possible universes, the reader is, of course, privy to the events surrounding those men who live on the most familiar and beloved Earth of the Marvel universe (dubbed Earth-616). The core characters who wrestle with this ethical conundrum are Captain America, the Sub-Mariner, the Black Panther, Doctor Strange, Hank McCoy the Beast, Reed Richards, and Tony Stark/Iron Man. Their anger, fear, comradery, indecision, and bold actions link the huge with the small and turn what would have been an ordinary cosmic opera into a full-fledged epic.

Next week, I’ll present a careful look at the timeline of events that comprise the full story. In third installment, I’ll be looking at the personality conflicts and revelations that make up the human element of the story. And in the final installment, I’ll discuss what I thought worked and what didn’t in both the literary and commercial fronts.