Starting with this installment, I’ll be reviewing and summarizing Peter David’s contribution to the canon of comic book story writing entitled Writing for Comics & Graphic Novels.

Peter David got his start in writing comics quite a bit later than most, beginning his career in the Marvel sales department before getting his break in writing some brief pieces for The Spectacular Spider-Man book. His real break came when Marvel assigned him to take over the writing reins on The Incredible Hulk, which had been a lack-luster title for decades (perhaps not always in sales but most always in content).

David creatively re-imagined the whole incident that turned Bruce Banner into the Hulk as a manifestation of a multiple personality disorder stemming from childhood abuse, thus turning Bruce Banner into a comic book version of Sybil. This approach not only revitalized The Incredible Hulk but it established Peter David as a writer of note and opened doors for him to write in other venues as well.

His strengths are focusing on characters and the small details that make them seem real and believable. Not surprisingly, the first half of his work on comics writing is focused on character and theme. The second half deals with the more mechanical aspects of story structure, plot, and scripting. I’ll be looking at the first half in this post, followed by part 2 next week.

It is fairly easy to summarize David’s point of view on the comics writer by simply looking at what he has to say on page 15

David sees a lot of similarity between movies and comics since the writer must think visually when crafting both. He claims that the storytelling arcs and techniques he’ll cover in this work are applicable to both. This claim may be true but I doubt the overlap is as broad as David asserts. As discussed in earlier columns on Alan Moore, the comic affords the reader with the same ‘choose your own pacing’ and ‘wait, let me review that’ features that written prose does and I think that makes a great deal of difference. Nonetheless, there’s no denying the strong visual component that both mediums demand of their writers.

In terms of characters, David believes that what readers want are characters to whom they can relate; characters that will cause them to make a personal investment of time and emotion. In his own words, a writer’s story stands or falls on his characters. However, he recognizes that the reader will often force an unrealistic consistency on a character – a kind of consistency that they themselves can’t live up to since they are human. He also recognizes that there are times when, either by design or inadvertently, the writer has the character acting contrary to established norms. During those times, the writer must keep the reader ‘in the loop’, as it were, and provide some mechanism to clue the reader that the creative team hasn’t lost its collective mind, even if that mechanism is as obvious as having the offending character acknowledge, “I just don’t know what’s come over me.”

Peter David also feels that a story is not real or meaningful unless the conflict is real and balanced. No straw man arguments – all sides need to be meaningfully represented (even if not endorsed). I suppose a reasonable way of interpreting his thoughts is that everyone has reasons for what they do and the better stories present the motivations found on all sides. He summarizes this approach with the maxim: ‘Make Everybody Mad’.

One way that he presents for getting every side heard is to craft a villain who stands in opposition to the hero’s perspective and then to give a credible reason for that villain to hold that view. This approach often leads to the villain not really being a villain but rather a character in opposition to the hero. So, conflict between two heroes is a viable plot point and common occurrence.

Another ingredient for realism is to express the small things in a character’s life openly. The examples he cites are the Hulk’s love of baked beans and the Martian Manhunter’s fascination for Oreo cookies.

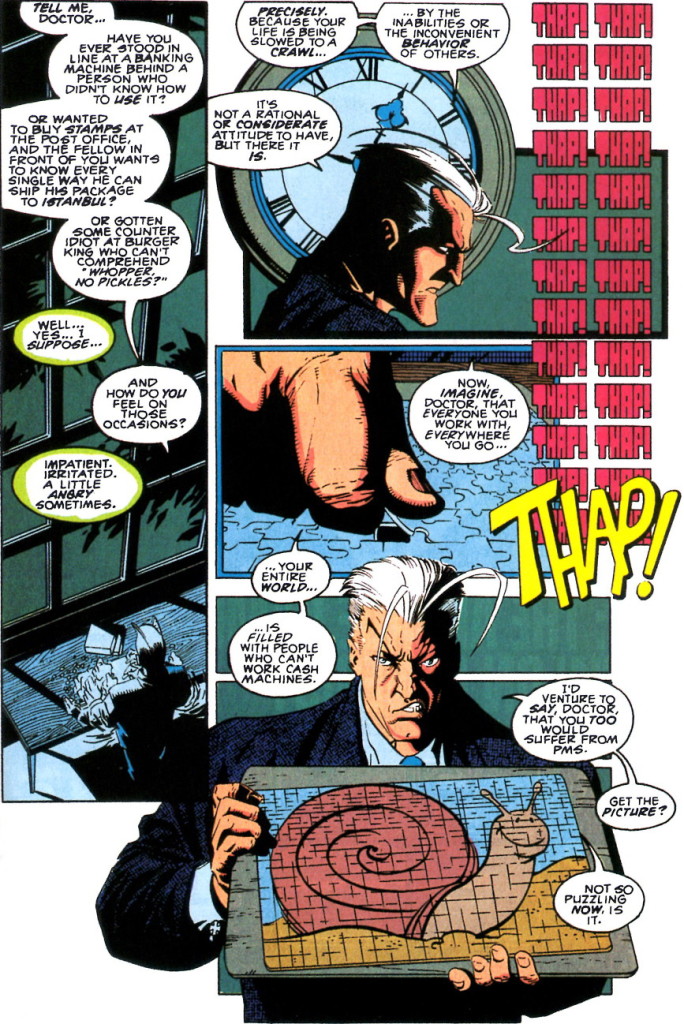

These humanizing details are one of my favorite facets of David’s work and easily his greatest strength. One of the best examples of this type of craft came while he was at the helm of X-Factor. In issue #87, he found a way to make Quicksilver truly memorable as a character. Up to that point, the Marvel speedster had always been either whiny and unsympathetic or sinister and unsympathetic. In one fell swoop, David managed to reinterpret Quicksilver’s entire past in one easy to understand scene

I recall this very scene as vividly today as when it hit the streets in 1993. In my opinion, it is the textbook example of what can really be accomplished in the comics medium; a method of storytelling that could only be done in a comic.

The other key component of the first half of his book is David’s universal analysis of stories and their relation, through conflict, to theme. At the most basic level, he views all stories as being able to be described in terms of what he calls three fundamental conflicts:

- Man against man

- Man against self

- Man against nature.

Since all drama is conflict, he views these three archetypal forms as the building blocks for drama. And the purpose of the drama is to flesh out a theme. The conflict illuminates the theme. Here, David provides a concise anecdote to describe his terminology.

How the writer actually reveals the theme is a delicate endeavor. And even what could be thought of as a clearly elucidated theme is always subject to the final interpretation of the reader. Nonetheless, the writer has to have a well-defined theme, so that, even if others disagree about the interpretation, they still agree about the general notion. For example, if the theme is about ‘with great power comes great responsibility’ then the drama should focus on showing the conflict between a duty-bound hero and his long-suffering wife who complains that the extra time he spends on his job should be spent with her.

Specific techniques that David advocates for managing conflict include:

- Tapping into family matters – father & son, mother & daughter, etc.

- Keeping the conflict small – small equals real

- Allow the characters to gaze in disbelief at the outlandish things happening to them – maintains reader buy-in

- Outfitting a hero with a personal weakness to accentuate his struggle with himself

- Try to generate a mix-and-match, six-sentence precis as a prelude to a full story.

Of course, there are lots of fine points that I’ve omitted and some very interesting exercises that are worth examination. But on the whole, the first half of David’s book is fairly structured with him emphasizing and re-emphasizing the same points about character, conflict, and theme discussed above.

Next week, I’ll finish my review of his book by covering the more technique-focused second half of the book on plot and scripting.