This is the final installment of the review of Denny O’Neil’s ‘The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics’, covering Part Two dealing with his techniques and advice for handling longer forms.

One of the shortcomings of ‘The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics’ is that O’Neil dumps a great deal of information into Part One on the single issue that is more logically housed with the longer form techniques. Much of the information that rightly belongs in Part Two deals with characterization, world building, and the techniques needed to fill and to manage page counts that are much larger than the standard 22 pages of glory found in a single issue.

His point-of-view on this can be roughly summarized to say that if the writer can handle the single issue well, he will have the skills and disciplines needed for tackling larger works. While I understand and appreciate this sentiment, it seems likely that O’Neil has developed this perspective from his experiences writing single issues for a pre-existing universe (Marvel and DC) and with pre-existing characters and series.

It is doubtful that a single comic covering an unknown world and sporting characters that are completely unfamiliar to the reader can meet the ‘Heavy-Duty Single Issue’ structure he advocates while simultaneously allowing the writer the space needed to build drama, interweave subplots (what would a subplot do in a single one-off issue anyway) and explore each character.

Had I been the editor, I would have structured Part Two on the longer form to cover building drama and building product, but alas I can only propose this structure after the fact. So in that spirit, let me review O’Neil’s advice in these two categories.

Building Drama

As mentioned last week, O’Neil is always conscious that he has a readership that he must attend to; a customer base whose desires and needs he must always be meeting. It is from this perspective that he tackles the concept of drama.

He basically defines drama as the conflict over the McGuffin, a term popularized by Alfred Hitchcock that means the thing over which the protagonist and antagonist are fighting or the device which triggers the plot. As discussed last week, O’Neil is all about rising action. Any effort that distracts from the main thrust associated with the McGuffin is wasted because it actually blunts the ‘emotional arms race’ he is trying to cause. Because of this focus on rising action, he favors the idea of suspense over surprise. Suspense clues the reader in to what is going on and allows the reader to anticipate what comes next for as much of the story as is possible, even if the characters within the story are ignorant.

For the long form, the tensions associated with the McGuffin play out over a larger page count and longer time frame. So it is natural to really take the time to explore the characters in the story in a way that the short form simple can’t accommodate. Doing so not only makes the reactions to the McGuffin more real, since they have a foundation, but it also prolongs the suspense thus improving the climax.

So exactly how should the writer explore his characters? The central questions that need to asked and, at least partially, answered for this discovery are:

- what does each character desire and wants does each have

- what does each love or cherish

- what does each of them fear

- what motivates them

These questions apply equally well to all characters in the story, even if they are not answered so thoroughly with the minor ones as for the major ones and, perhaps, most importantly, answers to these questions are vital for understanding the villains rather than the heroes. O’Neil’s ideas on character are that their actions speak louder than their words. So I suspect that he would recommend that a writer address each of these questions with an interaction (verbal, physical, cosmic, etc.) rather than with captions or dialog. Unfortunately, he doesn’t explicitly state his preferred method of tackling the inner state of the character.

But he does link characterization with subplots and states the subplots are good ways to introduce additional facets of the character’s lives. Being the consummate business man, O’Neil sees subplots as also serving additional the duty in the long form of setting up and sustaining prolonged readership but cautions that their use must be done with an eye towards the maxim that each comic book is somebodies first.

Building Product

Once the general idea of how to build the drama in the long form is decided upon the next point to work on is how big will the long form be? O’Neil distinguishes between 5 different types of long form work:

- Miniseries – between 2 & 6 issues with a definite story

- Graphic Novels – single publication with a much longer page count

- Maxiseries – usually 12 issues serving a grand or epic story line; crossover event

- Ongoing Series – standard uninterrupted series

- Megaseries – something like a crossover event but engineered on a bigger scale

Each of these has its own strengths and pitfalls and the interested reader is directed to read the details for himself. Roughly speaking, O’Neil believes that they all can be tackled with the 3-Act structure he discussed in the single issue context. For larger works (except the graphic novel) each issue should have a 3-Act structure, a set of issue should then interlock to have a larger 3-Act structure, and so on up the line.

The graphic novel is more fluid in that the story starts and ends in one book so the burden of carrying a reader forward, to coaxing the reader into buying the next issue, isn’t there. Nonetheless, I suspect that O’Neil would be inclined to say that working from the 3-Act structure for a graphic novel would be fine too.

Subplots are also important in the maxi-, ongoing, and megaseries, as they allow for smaller pieces to be introduced, grow, and mature. Of course, subplots have been the staple of all serialized fiction for decades so much of what O’Neil has to say on these points should be obvious to all but the most inattentive watchers of ongoing TV shows or readers of serialized fiction. He does make a useful distinction between story arcs and what he calls the Levitz Paradigm.

Story Arcs, by his definition, are complete stories that cover multiple issues but which are connected to the ones before and after by only tenuous threads. There are definite jumping on and off points and a collection of multiple issues can stand on their own as a graphic novel after the initial run.

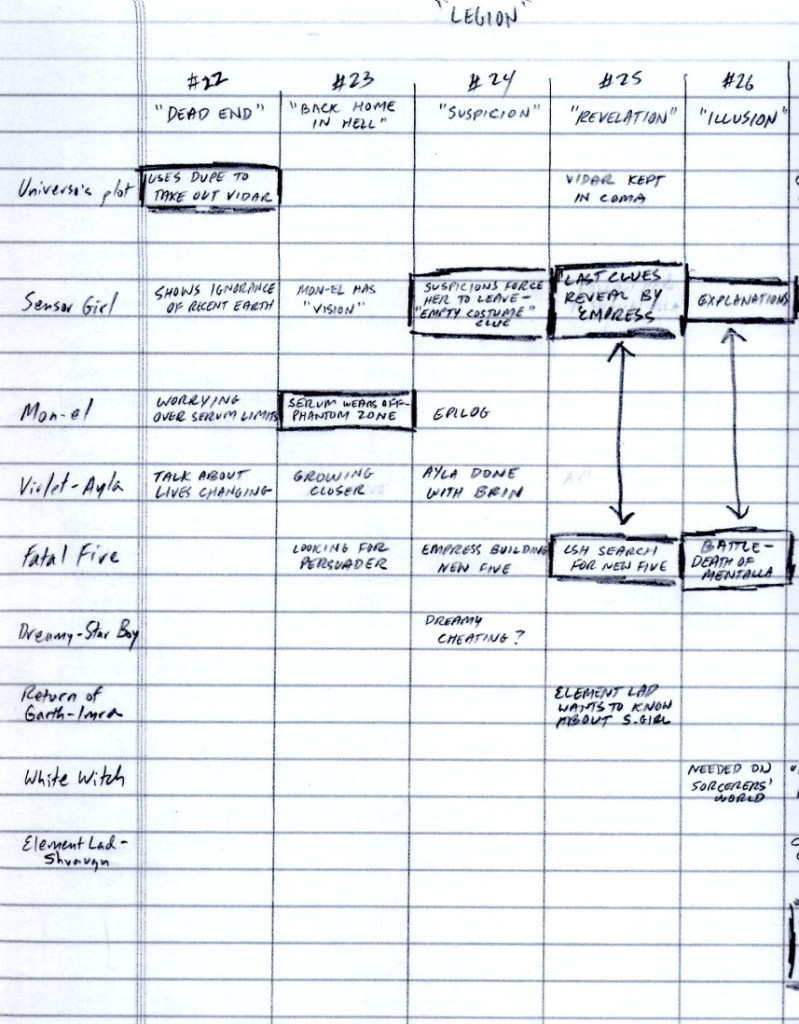

In contrast to Story Arcs, the Levitz Paradigm works with multiple overlapping story lines that grow from cold, to cool, to simmer, to boiling over. As one moves up the heat scale another is placed on the open spot and so on. With this technique, there really isn’t a jumping on or jumping off point. So if the readership can be hooked it will tend to persist. An example of the Levitz Paradigm for ‘Legion’ is shown below.

One last note is worth discussing about the long form – continuity. Whether it is the demographics that are reading comics, the internet’s ability to serve up fast answers, or some other factor or factors, it is clear that audiences in all media desire continuity. O’Neil recognizes this trend and categorizes the types of continuity into three kinds which he labels ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ but which, for convenience, I’ll call, puddle, pond, and ocean.

The puddle type of continuity covers the basic notions that characters should not change names, or hair color, or other simple traits (without reason) during the course of a story. It is the simplest and smallest type of continuity and one which the writer should be maintaining. The pond continuity is a bit bigger and covers all the critical back story events of a character that may not be in play in the story being told but which must not be contravened. This type of continuity is important, although the writer may not be solely responsible for maintaining this one. The ocean continuity is the vast universal continuity that covers the shared universe that all DC characters inhabit. O’Neil doesn’t have much in the way of constructive advice for this last type of continuity and, frankly, who can blame him. Tangles in this kind of continuity have driven Marvel and DC to numerous reboots of their universes.

Final Thoughts

Overall, I wouldn’t claim that the reader will get well-structured advice with a pedagogical touch from O’Neil’s book. There isn’t much in the way of a how-to or a best-practices. Rather, his book is like picking the mind of self-taught veteran for all those pro-tips that you usually get only one at a time when working side-by-side with an expert. It is from this point-of-view that the O’Neil’s work is best consumed.