This week’s column turns its attention to ‘The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics’ by Dennis O’Neil.

Denny O’Neil is perhaps best known for his Green Lantern/Green Arrow stories from 1980s. These tales brought a new level of maturity and social relevance to comics as they continued to struggle to regain the ground lost during the retreat in the 1950s. They also made Denny O’Neil a bit of a household name, at least in comics circles.

O’Neil is a somewhat old-school in his approach and his descriptions and, frankly, it is actually quite nice. He has a customer focus that I like. He seems always to be oriented towards selling a story to his readers, not because he is a crass peddler of so-so melodrama that he has no investment in but rather because he seems to really care about telling stories. To wit, he opens the book with a very nice sentiment about stories:

That said, he does tend to wander a bit and key observations are sometimes located far from related points. In addition, the overall composition of the book is a bit disorganized, which is a bit ironic, as will be discussed below.

For O’Neil, a story is a structure narrative that should resonate on at least one of three fronts; a story should have an emotional effect, demonstrate some important point, or explore a character (hopefully all three).

Having established that his goal is to help the reader tell a story that hits one of those points, the rest of the work is devoted to how might the would-be writer accomplish such a task. The book is divided into two parts. The first and largest part concentrates on delivering the story within the confines of a single issue. A point that only becomes apparent near the end of part one (last paragraph actually) when he finally says that everything up to this point deals with writing a single, self-contained issue. The second part deals with mini-series, graphic novels, maxi-series and crossovers, and ongoing, interlocking series. Some of the most interesting tidbits are found in this part but for now I’ll be reviewing and summarizing Part One this week. Next column will cover Part Two.

Stylistically, Part One is crafted more like having a dinner conversation with an old friend who you haven’t seen for a long time. The narrative flows back and forth between interesting anecdotes and the exposition of general principles. Overall, it is reasonable to say that O’Neil covers three main areas: Story Structure, Techniques, and Practical Advice.

Story Structure

In Part One, O’Neil provides a quick-and-dirty list of story structure – or at least he thinks he does. Actually, the list seems to be made up of only two entries: One-Damn-Thing-After-Another and O’Neil’s Heavy-Duty Single-Issue Structure.

The One-Damn-Thing-After-Another is listed more as homage to the early works where the action came fast and furious. The plot, defined as the time ordering of events, was central at the expense of story and so the writer is encouraged not to use it except perhaps in rare and controlled circumstances.

The rest of this chapter is spent on the Heavy-Duty Single-Issue Structure. What O’Neil defines as the essential attributes for this structure can be succinctly summarized. The structure consists of 3 acts.

Act 1 opens with a hook, possesses an inciting incident, and establishes the situation and conflict over the McGuffin (what the hero and villain are fighting over). The hook should be an action scene, pose a question, or present some type of danger. It should never be used solely as an establishing shot and never be wasted on an inanimate object.

Act 2 develops the current situation by laying in complications which take the plot in a different direction. It should also have major visual action.

Act 3 contains the events leading to the climax and includes another dose of major visual action. It should close with a denouement that returns the old status quo or establishes a new one.

Techniques

One of the many travelers’ tales that O’Neil treats the reader to is a discussion about just how Stan Lee handled the large work load he had in the Marvel early day. As the story goes, Lee would often simply confer with his experienced artist partners, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, discuss with them the bones of the plot, and then trust them to deliver on the pacing and art against which Lee would write the narration and dialog.

This approach forms what O’Neil calls the Plot-First approach to story structure. Since few of us are either Lee or Kirby or Ditko, O’Neil suggests that the approach be started with a plot typed up in a few paragraphs and sent to the artist who then returns about 125 panels for the writer to add the written word. He lists three advantages that the Plot-First approach affords:

- Writer can fix omissions in the after the fact

- Writer can be inspired by the art

- Writer can be lazy/efficient

In the first point, O’Neil is explicitly recognizing that the comics art form is still a business with a customer base that expects product out on a regular schedule. Mistakes happen and he is acknowledging an advantage that makes meeting a deadline easier since the writer can adapt the story to the art rather than the artist having to go back and fix the panels. Likewise, the third point is also deadline-oriented, allowing for the possibility that the writer may be engaged in other and equally important activities. Only point two is devoid of any sense of managing deadlines and is solely focused on the quality of the product itself.

In contrast to the Plot-First approach, O’Neil offers the Script First approach. Here the comics writer is far more akin to the writer of a movie or television script. Each ‘shot’ is detailed along with the basic flow and tempo.

He also lists three advantages of this method:

- Writer in full command of the story

- Writer can change the story quickly since rendering isn’t started

- Writer is in charge of his deadlines

O’Neil clearly regards this approach as the one that put the writer closer to his art or craft. Nonetheless, he never lose sight of the practical considerations that enable the writer to efficiently work with his artist (point two) and his career (point three). He does suggest that a writer who employs the Full Script technique try to sketch the layout before submitting the final form. He cites Archie Goodwin and the success he had following such a practice.

Practical Advice

Perhaps the greatest strength of this work is the tidbit of practical advice that O’Neil peppers throughout the discussion. There is structure for when they appear or how they connect. Instead they seem to occur when some piece of the structured presentation triggers them and they form the anecdotes mentioned above.

As a result, there isn’t really any point in building a grand narrative to house them and so I’ll simply list the ones that captured my attention.

- Don’t underestimate the importance of the splash page for setting the mood, establishing the story, and easing the reader into the story. O’Neil is against the modern practice of pushing the splash page to later pages.

- Captions are to be avoid when dialog balloons will suffice. O’Neil cites one editor who believes that many readers even skip the captions and he further cites the notion that nothing grabs a reader’s attention as much as ‘listening’ to what a character has to say.

- Know the end before you write.

- Start scenes at some point of interest (skip the mundane). Nobody want to see the characters get up and brush their teeth (unless, I suppose, an assassination attempt occurs just at the moment they start to gargle).

- Generate rising action by ratcheting up the tempo.

- Distinguish between surprise and suspense. Used here, the two terms are antonyms with suspense being preferred since surprise only shocks the reader for a few panels (before the understand) whereas suspense builds over long periods of time as they know generally what is going to happen but not how.

- Never write a panel or scene that doesn’t contribute to the plot.

- The hero must be agent of the story’s resolution – he must act and be involved (even if he is the anti-hero)

On piece of advice is worth particular attention. O’Neil stresses that the exposition be clear. Writer’s must go out of their way to ensure that the reader is following. For example, the writer must make flashbacks visually delineated from the normal flow. The reason for this emphasis is best understood in O’Neil’s own words

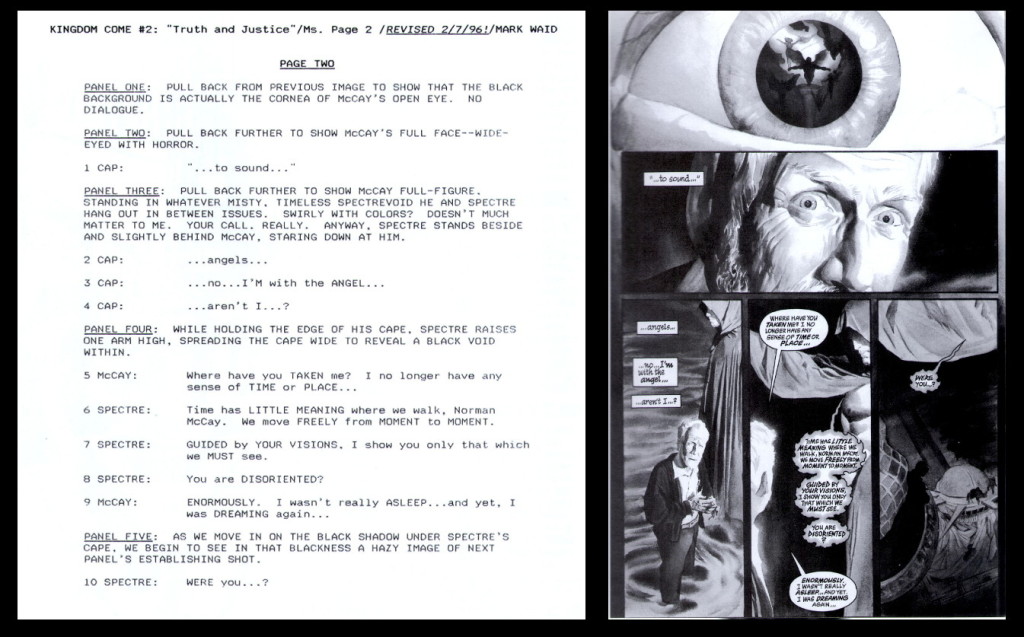

Ironically, things are not always clear in his exposition in this work. For example, the layout between pages 22-23 obscures the connection between the textual and visual ordering of the mechanical steps of page construction (i.e., script, pencils, inker, letterer). The text calls each out in the traditional order but the visuals aren’t labeled. Elsewhere, what appears to be a visual example of the Full Script technique is juxtaposed with text talking about Plot-First.

Nonetheless, Denny O’Neil’s take on single issue story construction is a fun and valuable read. Next week, we’ll see what he has to say about larger-scoped works.