Watching the Watchmen – Part 2

Last month I reviewed the compositional elements of Watchmen that made the book a genuine work of comic book art. Moore and Gibbons primarily used 5 different and complementary compositional elements (page layout, panel detail, background material, repeated visual elements, and repeated narrative elements) in a consistent but unobtrusive way during the 12-issue run and, in doing so, created a critical and commercial success.

This month I want to examine the underlying philosophical themes and messages that the story conveys. The central point with which Watchmen wrestles is one of existential nihilism; the notion that human life is meaningless, banal, without purpose and that morality, as a result, is a convention or societal trapping at best.

While Gibbons claims that Watchmen ultimately celebrates the superhero genre and, therefore, rejects existential nihilism, there is little in their work that actually supports this assertion. It is true that at ‘the end’ of the series, a sort of equilibrium is achieved wherein the surviving main characters have found that the human race has value (no individual member per se; simply the race as a whole), but the justifications rest on weak first principles about the nature of man. Throughout the series, it is easy to find Thomas Hobbes’s famous characterization of human life as being ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’ being expressed by almost every character, large or small, each in his own distinct way.

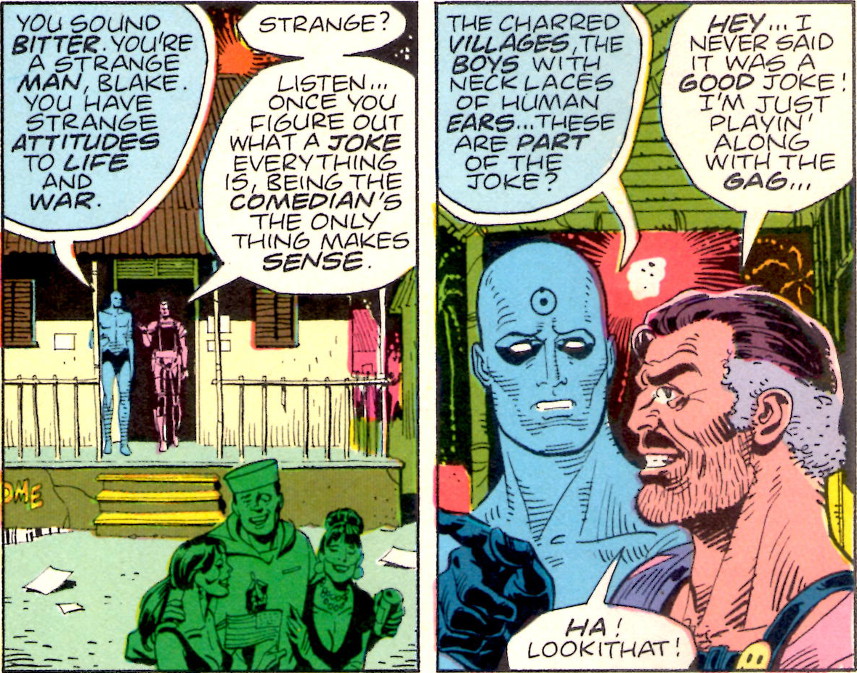

The Comedian (aka Edward Blake) is by far Watchmen’s poster boy of existential nihilism. His code name derives from the cynicism he has about the value of human existence and the fact that he sees into ‘the joke.’ As a result, he doesn’t put a lot of stock in humans or their institutions and Moore and Gibbons afford us many opportunities to see inside of his philosophy. The most telling are his interactions with Doctor Manhattan (aka Jon Osterman) in the Viet Nam war. At Blake’s funeral, Manhattan reminisces about their time in Viet Nam.

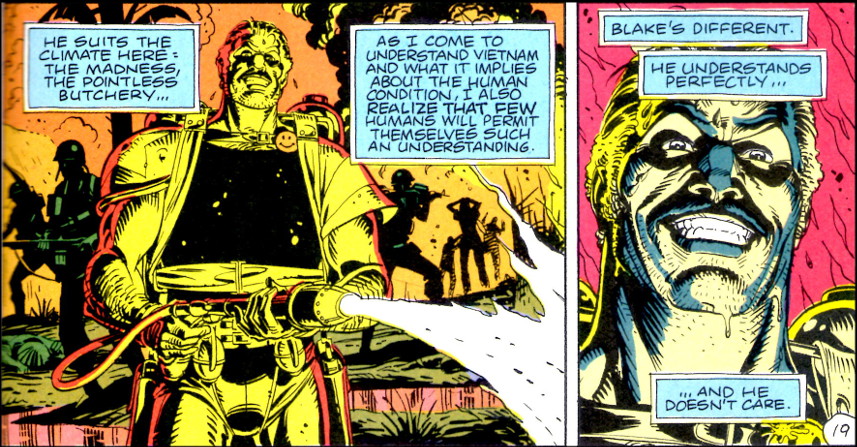

The time they spend together seems to have a profound effect on Doctor Manhattan, driving his already detached attitude even further away from compassionate sensibilities and into cynicism of his own.

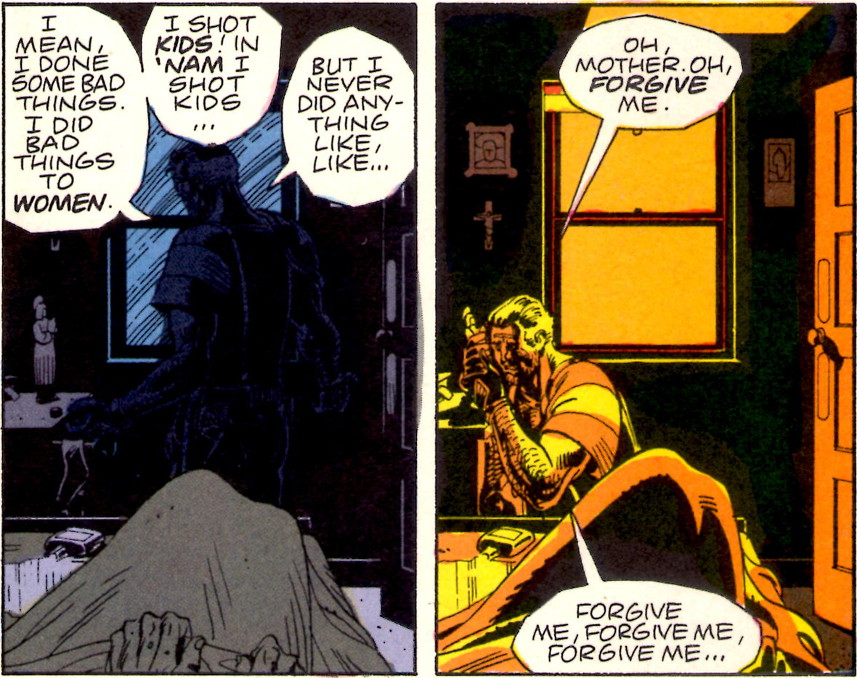

The Comedian’s own attitude seems to shift as he gets older and his cynicism, it seems, has limits. Moloch, once one of the most feared crime lords in the Watchmen universe, becomes an unexpected confidant of the Comedian’s. Blake breaks into his apartment for a little heart-to-heart. Having discovered Ozymandias’s (aka Adrian Veidt’s) plot to sacrifice millions to save billions, Blake is on the verge of a nervous breakdown and openly weeps in front of Moloch as he opens his soul about his past sins and how disturbed he is over Ozymandias’s plan.

It isn’t explicitly stated but I am left with the impression that this change in Blake’s attitude is the result of his realization that his own daughter could be one of the victims of Veidt’s plan. In other words, that Blake finds some limit to his nihilism seems to result from the biological fact that he has a child.

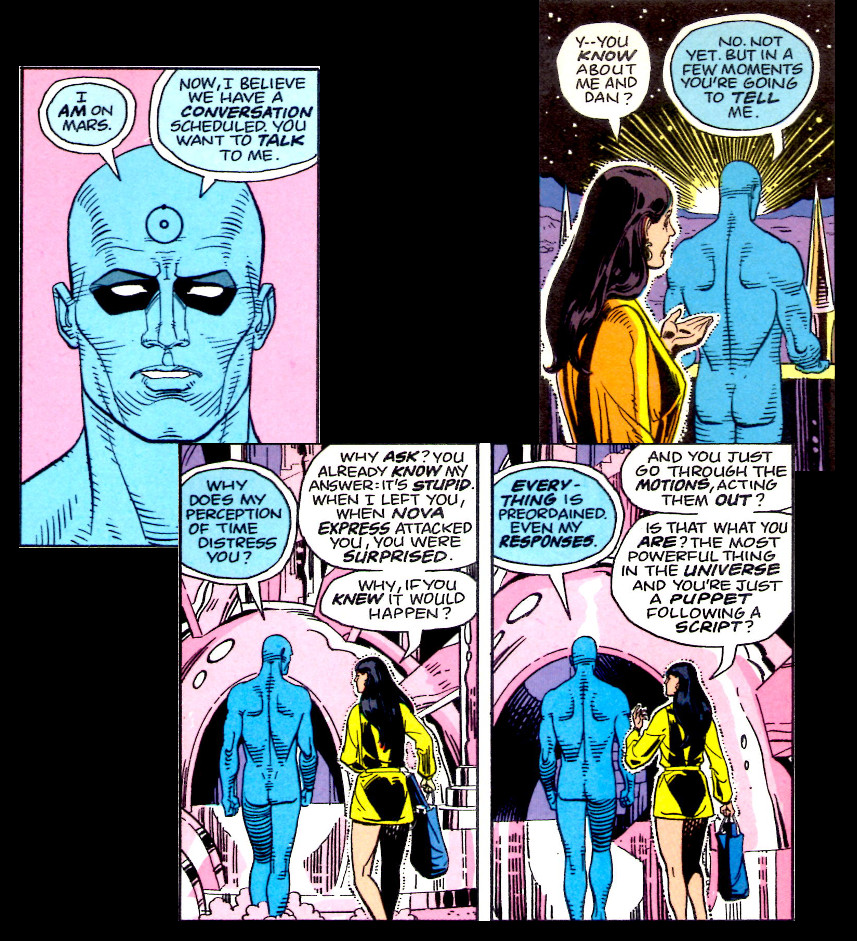

By the start of Watchmen, it is uncertain how much of Doctor Manhattan’s attitude is shaped by his interactions with the Comedian and how much is the result of his ‘other-worldliness’. What is certain is that he claims to no longer find value in human life,

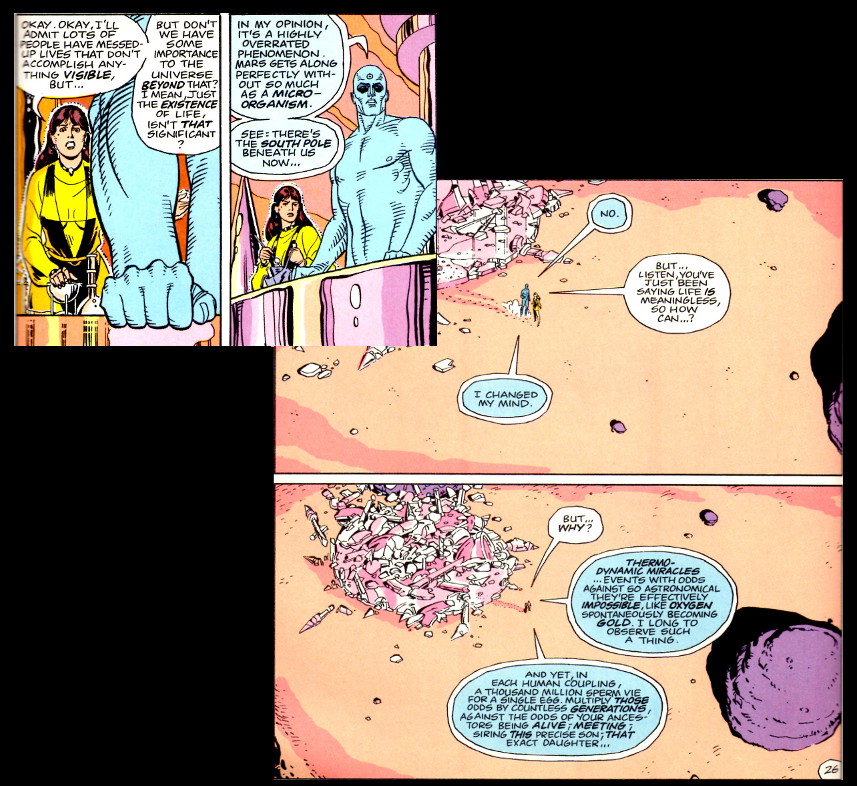

despite the fact that he has a human lover in the form of Laurie Juspeczyk (Silk Spectre II). Regardless of what he says, Jon still possesses enough human emotion to be easily manipulated into leaving the Earth for Mars. His absence is engineered by Veidt/Ozymandias precisely so that the latter will have no impediments for his great plan of salvation (essentially the same reason that Veidt kills the Comedian). However, Jon’s emotional attachment to Laurie Juspeczyk leads him to bring her to Mars, where she tries to convince him that human life has meaning.

Each of her arguments fails utterly and it looks like there is no possible way for her to convince Jon to return to save the world. It is only in the last minutes of their dialog that the situation changes. Jon unwittingly enables her to correlate all her memories and to realize that Edward Blake – the man who once tried to rape her mother – is her father. This sudden realization changes Jon’s perspective on the human race and allows him to see people as a thermodynamic miracle.

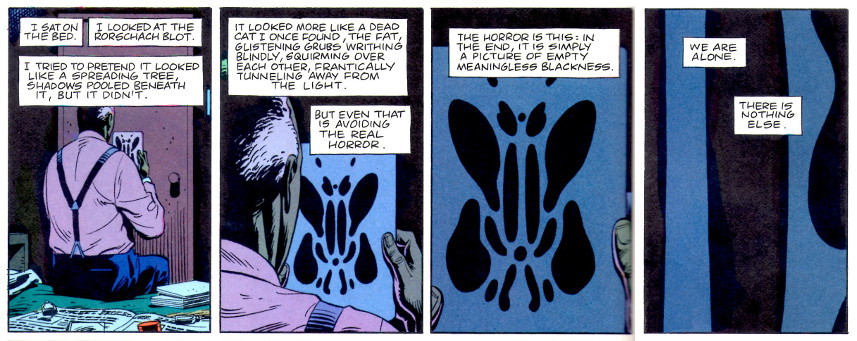

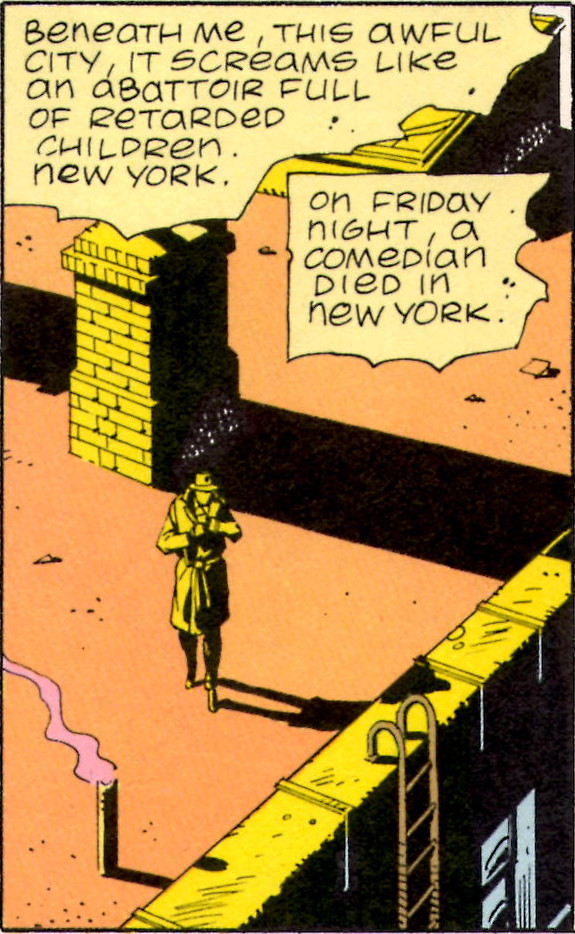

The most curious attitudes about the human race come from Walter Kovacs (a.k.a. Rorschach). Outwitted and framed by Veidt for Moloch’s murder, Kovacs is captured by the police, held at Sing Sing penitentiary, and forced to undergo mandatory psychological counselling by Malcom Long.

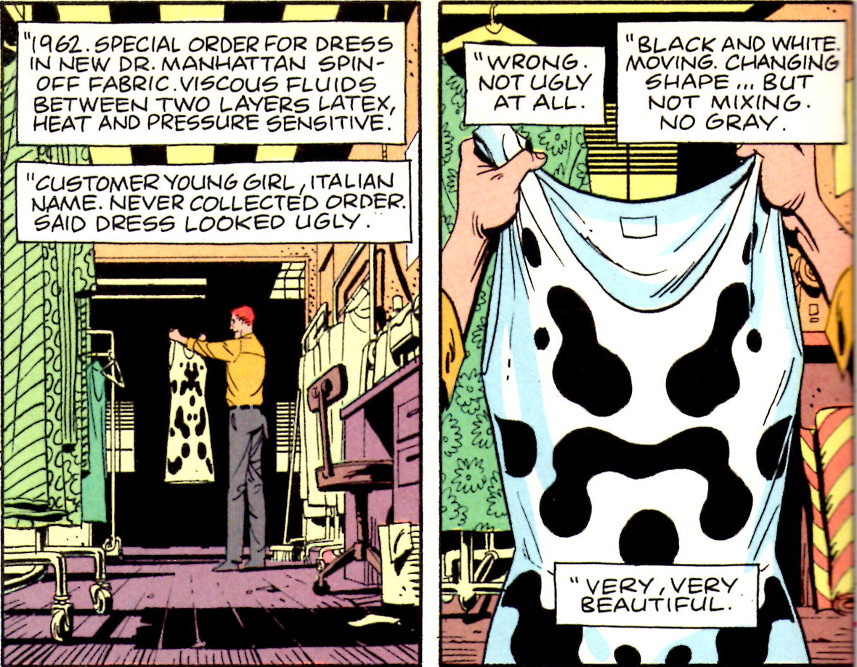

After days of evasion, Kovacs explains to Long how he got his unique ‘face’

and the connection between this ever shifting viewpoint on black and white and how he decided to adopt Rorshach as his superhero persona.

It should be noted that the modern viewpoint of the Kitty Genovese story is that the New York Times exaggerated the indifference of the neighbors, neglected to mention that the cops were called twice, and failed to state that no one could clearly see or hear what was happening in that alleyway. Nonetheless, Moore makes a lot out of this story and how it influences Kovacs into becoming Rorshach.

The last evolution for Kovacs occurs when he takes on the case of the kidnapping and butchering of a little girl. The particular brutality of the monsters who killed this little girl when they realized that she wasn’t the daughter of a rich man but simply shared the name drive Rorschach into becoming a monster himself. After that pivotal event, Rorschach is the prime personality and Kovacs is the mask.

The title of issue #6, in which Long discovers the truth, is The Abyss Gazes Also, a clear reference to the famous quote

Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you. –

And true to this sentiment, by the end of the session where Malcolm Long discovers the truth behind Rorschach, he too is embracing nihilism.

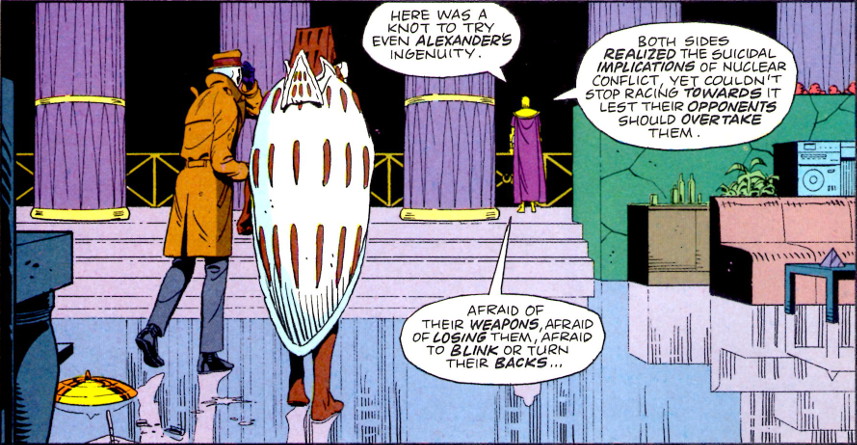

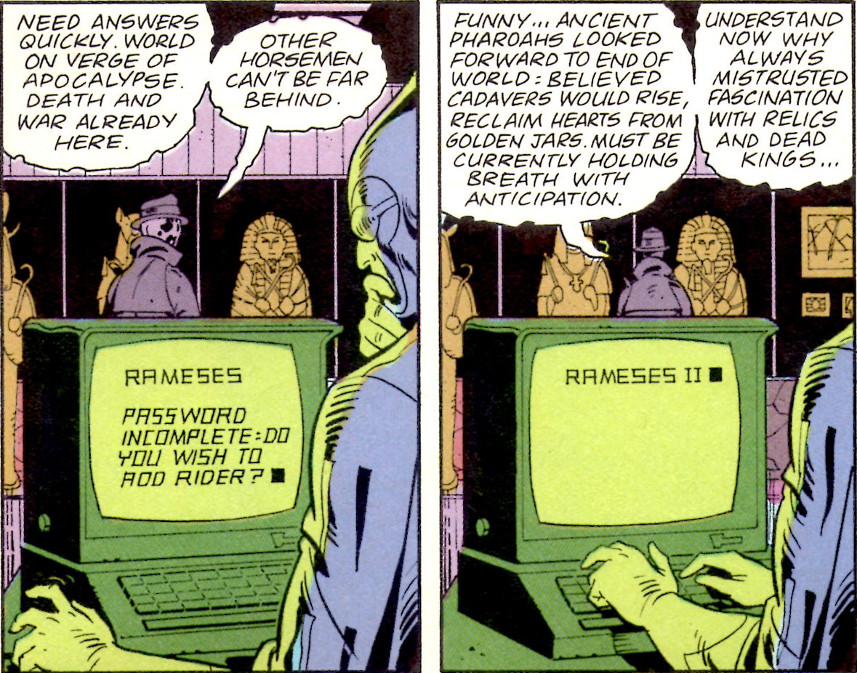

Perhaps the most interesting of all the Watchmen characters is the one who, through the bulk of the series, gets the least attention – Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias. Dubbed the most intelligent man on the Earth, Veidt is fascinated with the ancients and their approach to life. In particular, he admires the campaign and conquering of Alexander the Great, even though he has taken as his superhero name the Greek name of the great Pharaoh Ramses II.

Originally planning to make a difference as a costumed adventurer, Veidt’s perspective changes abruptly under the influence of the Comedian, who argues that no amount of small scale crime fighting will change the basic equation of the Cold War.

Soon after, Veidt gives up his masked persona and seemingly retires to become a highly successful captain of industry 2 years before the government eventually declares all masked adventurers outlaws. In actuality, Veidt is merely the mask that Ozymandias wears as he engineers his world-saving solution. As he explains to Rorschach and Nite Owl, the Cold War was a modern Gordian Knot; something that needed to be solved by out-of-the-box thinking.

Thus Ozymandias engineers the plan for a mock alien invasion that will unite, at least briefly, the entire Earth as one brotherhood.

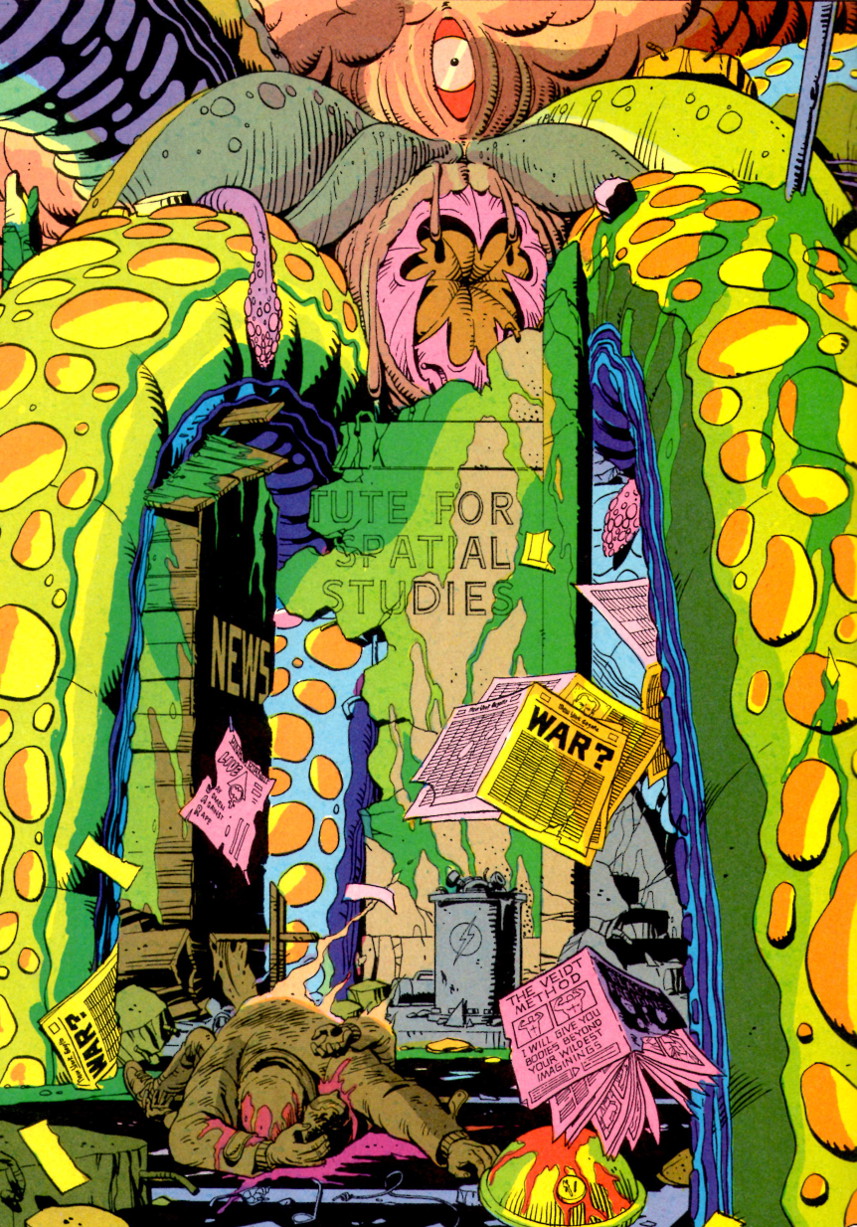

The fact that millions die so that billions live is something that Ozymandias seems to be able to live with and justify. Nonetheless, Moore and Gibbons suggest, though their Tales of the Black Freighter comic-within-a-comic, that Ozymandias through his struggle to stop the monsters of the human condition has become one himself.

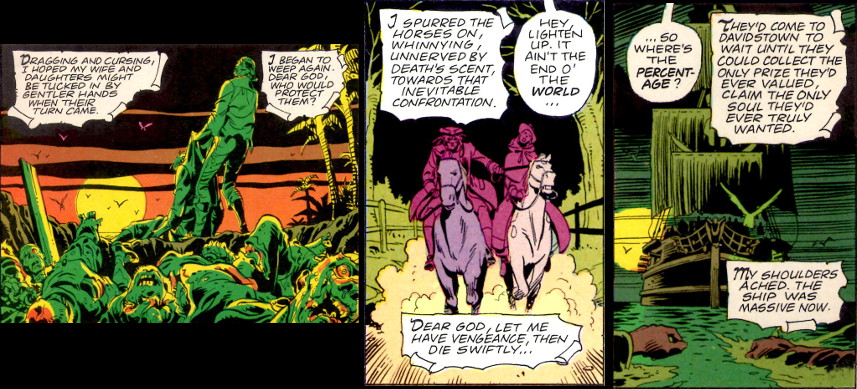

The Tales of the Black Freighter is introduced and presented to the reader through a young boy who hangs around a newsstand to read the reprinted editions of this classic horror comic written years before. This comic-within-a-comic is visually distinct from everything else in the Watchmen and is given out in installments. As a compositional element, it is interesting in that it serves at least three distinct functions: it gives homage to the old EC comics of the 1950s; it represents one of the few attempts at a frame tale in comics; and it serves as a vital element to explain Ozymandias’s psychology.

The two-part story focuses on an unnamed man who is marooned on an island after his ship has been attacked by the ship from hell called the Black Freighter. Initially dismayed by the threat the damned pirate ship represents to his home town, the man fashions a raft from the dead bodies of his compatriots. The horrors he endures and embraces eventually take him from genuine concern for this family, through the hunger for vengeance, and finally to a willingness to sacrifice innocent lives to see his loved ones protected. This final action results in his ultimate damnation aboard the very ship he loathes.

This narrative metaphor is meant to emphasize the sentiment of Nietzsche who warns of the cost when battling monsters – a theme that Moore attaches to the actions of the superheroes of the Watchmen.

Of course, not all characters embrace nihilism. There seem to be three or four genuinely ‘nice’ characters: Nite Owl I (Hollis Mason) and II (Dan Dreiberg), and Silk Spectre I (Sally Jupiter) and II (her daughter Laurie Juspeczyk). The positions and arguments against existential nihilism from these characters are not mounted in any serious way. Both Mason and Dreiberg are portrayed as powerless characters. Mason dies at the hands of a gang of hoodlums, and Dreiberg (who is the ‘knight’ of the story – see the additional material at the end of issue #7) is shown to be both sexually and strategically impotent. Sally Jupiter is shown to be in it for the money and to be materialistic and shallow. Laurie is first introduced as the sex kitten used to keep Doctor Manhattan happy and, when introduced later as a costumed adventurer, she, of all the main characters, is not provided a dramatic pose that features her alone (see the team image from last month’s post).

So, what to make of existential nihilism in Moore’s story? Well, it seems that Moore pulls from Nietzsche here as well, when the latter states “If we affirm one single moment, we thus affirm not only ourselves but all existence.” But the affirmations provided in Watchmen are weakly supported and full of strong metaphysical contradictions. For example, the Comedian’s point about seeing the joke implies the existence of a jokester to tell it, in turn implying purpose to human life; a point further emphasized by Blake’s ‘biological repentance’ once he knows he is a father. Doctor Manhattan’s grasp of thermodynamics, statistical mechanics, the structure of spacetime, and quantum mechanics should afford him a better grasp on metaphysics so that the human mating revelation he has on Mars should have never needed to be. This is especially troubling given the notion of predetermination that comes from Doctor Manhattan’s ability to see past, present, and future simultaneously.

Rorschach finds only value in abstract things like Justice and Truth but finds no motivation in Love or Beauty, so how does he truly know Justice? So he hates the human race, for whom he fights, but continues on fighting.

Ozymandias sees only value in control, so the thing that is worth controlling (here the human race in total) has value, but it isn’t clear why he values the race while valuing no single member within. In addition, the world’s smartest man, who is capable of engineering this alien invasion plan, is not smart enough to have standard password protection.

The superhero genre, like the classic epics and mythology on which it is built, always has nobility and baseness side-by-side. Characters of profound capabilities put their gifts to use, both good and bad, even if they themselves are not necessarily good or evil. The classic superhero story doesn’t deny the existence of horror or evil, but rather celebrates those individuals who can look into the abyss without becoming monsters. In the Watchmen one finds only the baseness, only the abyss, and only the monsters.

So if the compositional elements of Watchmen can be regarded as the wrapping paper on the outside of a gift box and the themes of existential nihilism can be regarded as the gift inside, then the Watchmen is one gift best admired for how it looks unopened.