In this piece, the 3-month-long look at the Marvel experiment called the New Universe comes to a close. The previous two articles discussed the overall original concept and the short-lived series that were repurposed halfway through their run to provide the supporting material for the series that survived. This article will examine the series that made it to the end (D.P. 7, Jvstice, Psi Force, and Star Brand) and the corresponding limited series (The Pitt, The Draft, and The War) that were used to create the backdrop of world war and paranormal involvement in the conflict.

As a result of the ‘editorial renavigation’ at the end of year one, what were once loosely-connected titles transformed into a set of commonly-themed tales all branching off of a main trunk. This new approach apparently worked, as sales of these remaining titles increased and, according to Fabian Nicieza – who got his industry start as a writer on Psi-Force, the four remaining NU titles were profitable up to the end of year three when Marvel pulled the plug.

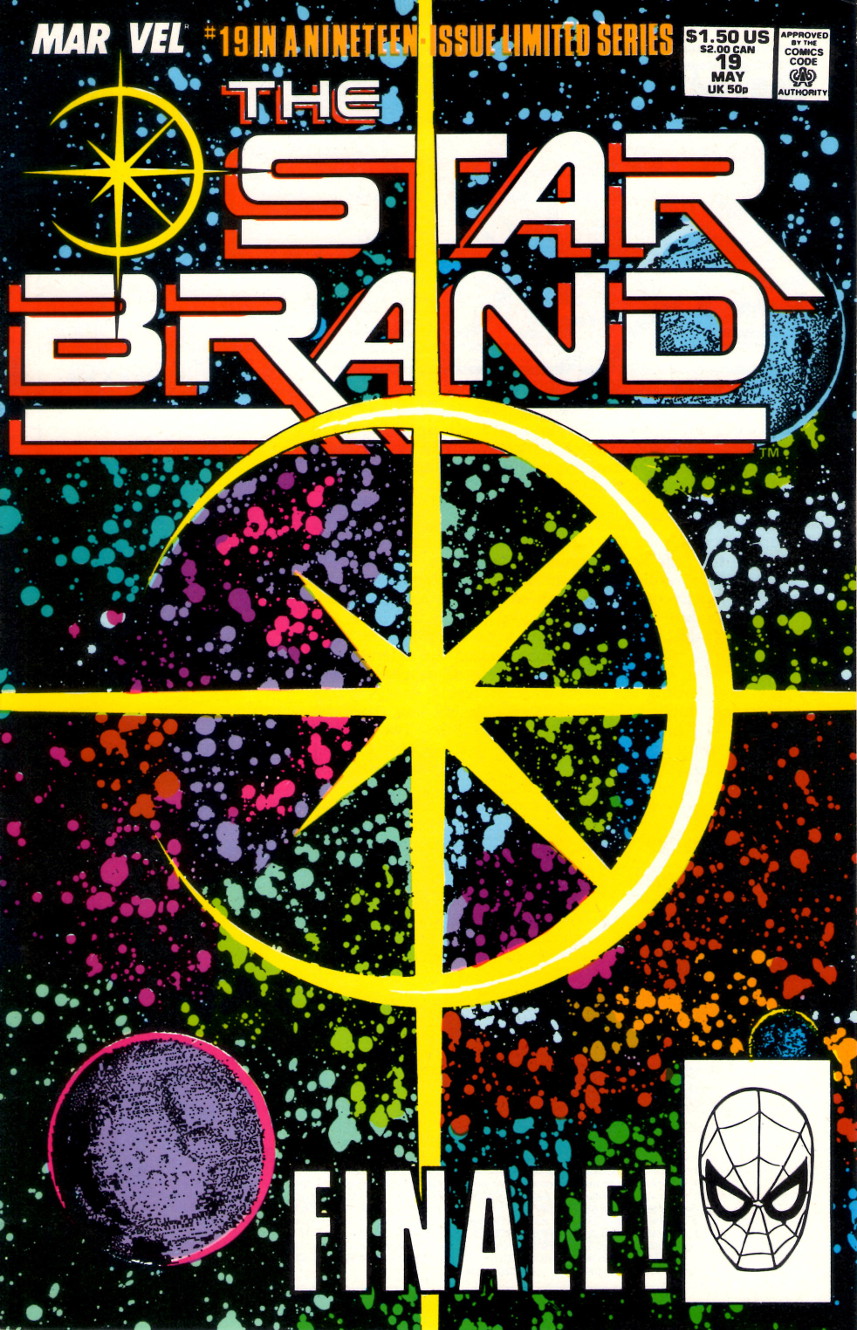

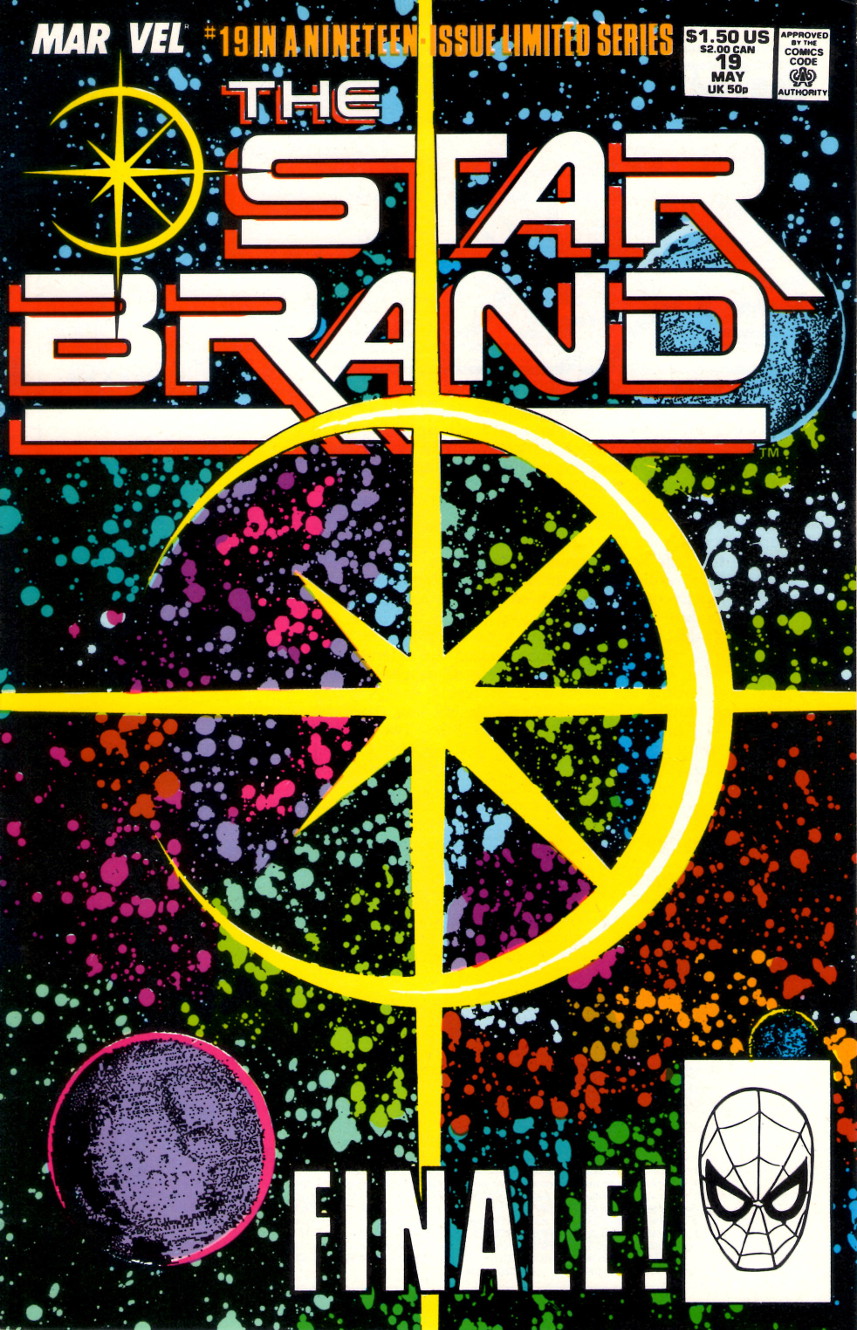

Why, exactly, Marvel ended the imprint isn’t clear; Nicieze simply says that Marvel wanted to go in a new direction. The likely explanation is that, while profitable, the New Universe tied up resources that could have been used elsewhere for an even larger return on investment. Whatever the reasons, as the New Universe drew to an end, Marvel did two things that are quite interesting. First, it promised and actually followed through on a limited series, The War, that tied up most of the loose ends associated with the World War III overarching storyline. Second, each of the remaining titles bore an inscription above their titles for the final issue declaring that that issue was ‘#19 in a Nineteen-Issue Limited Series’.

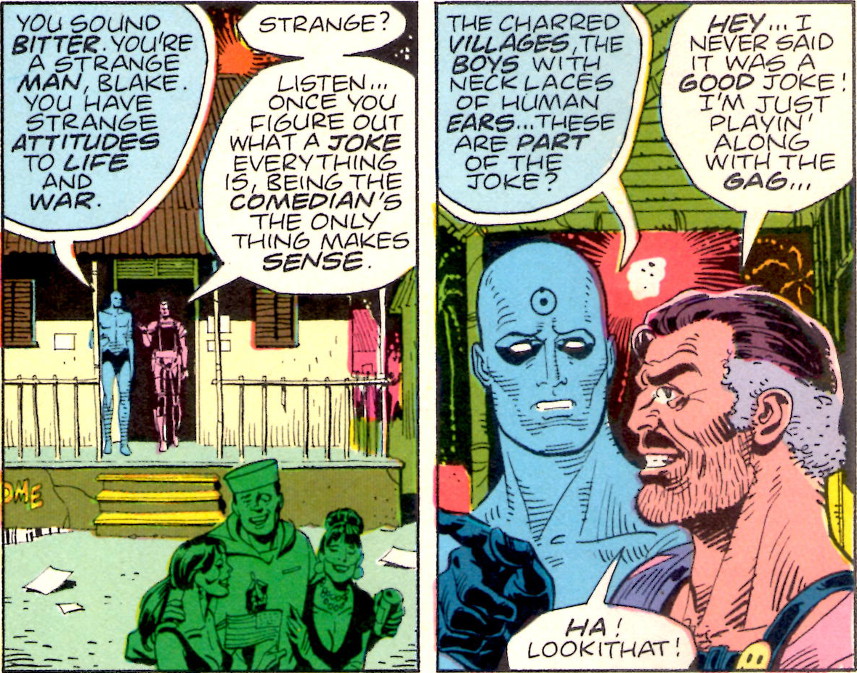

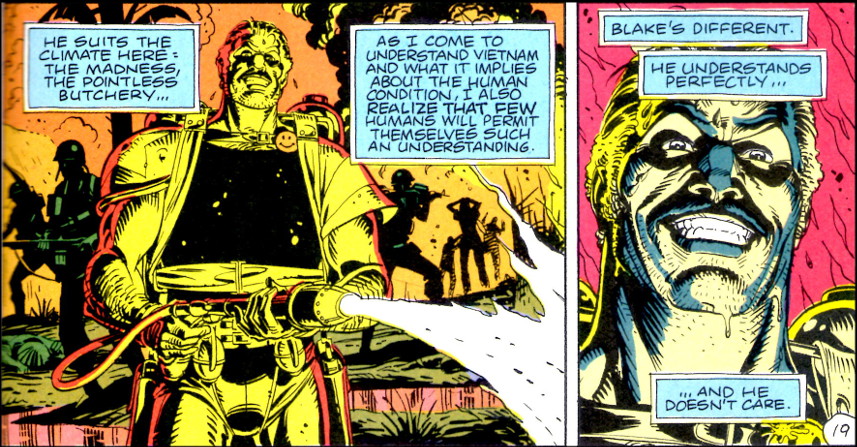

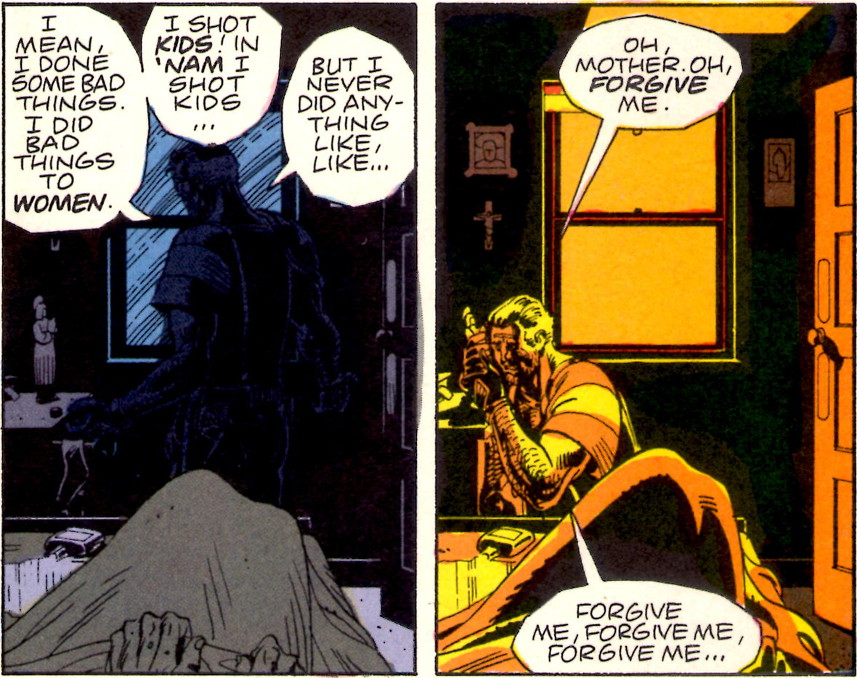

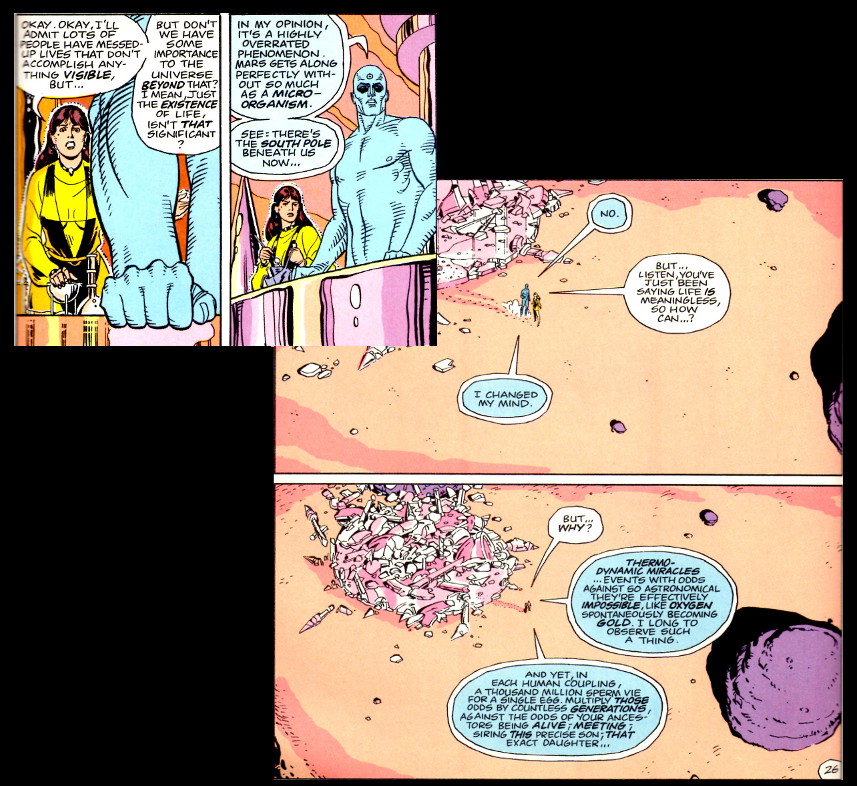

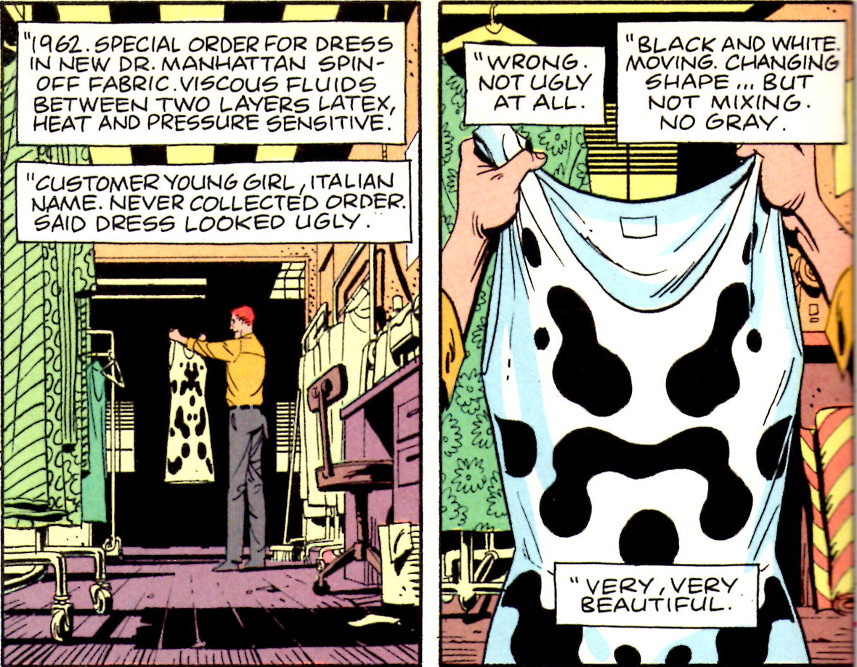

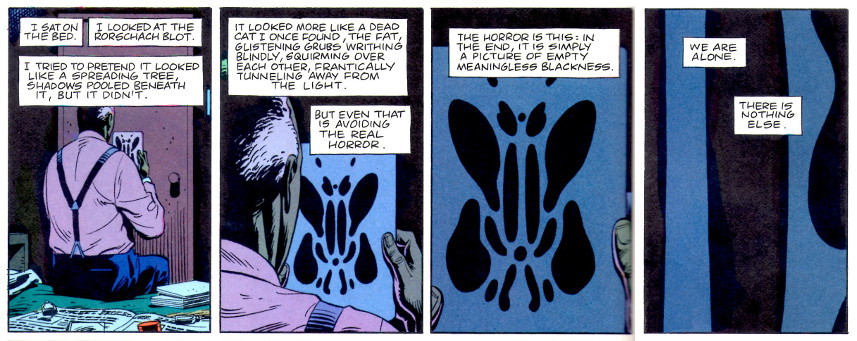

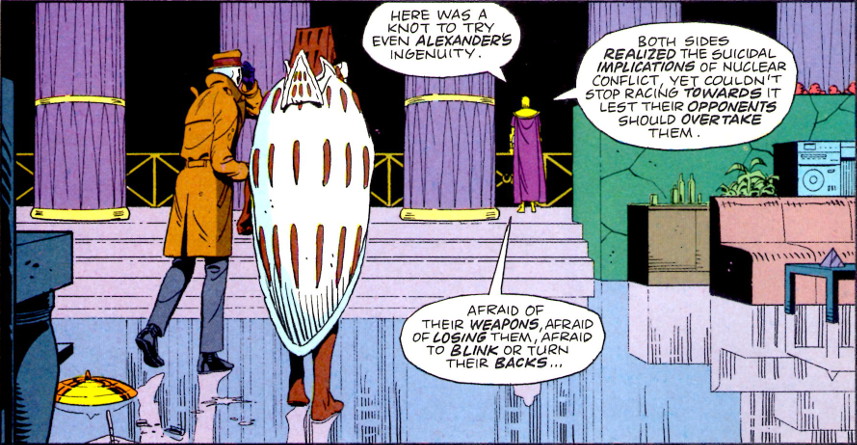

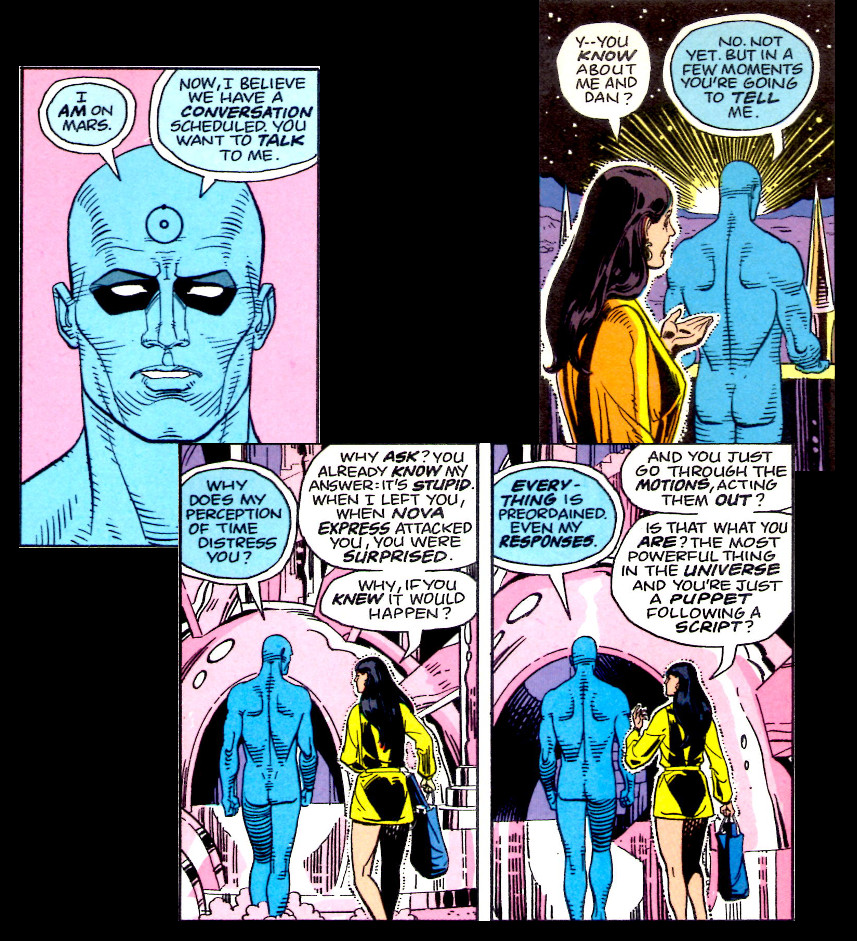

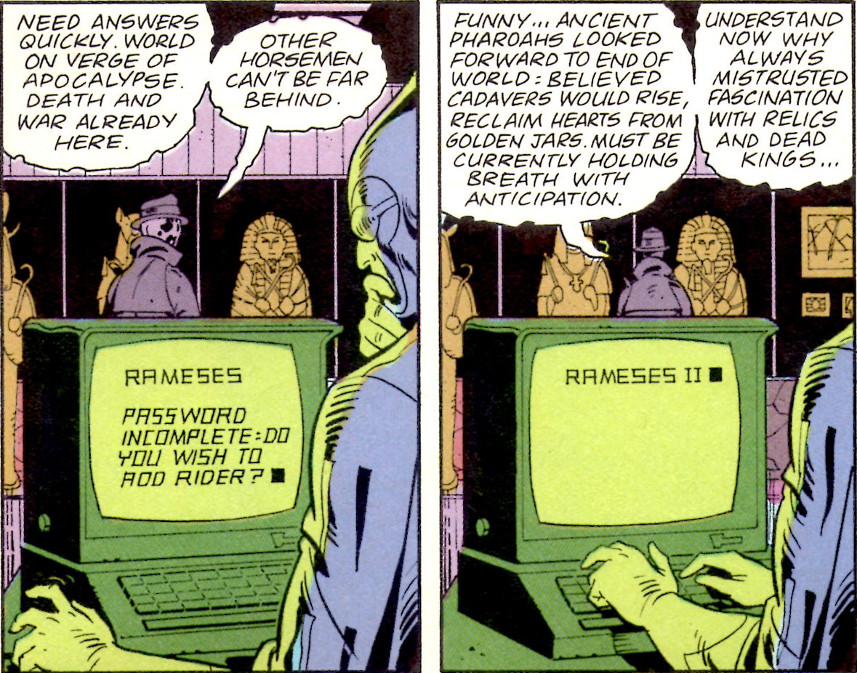

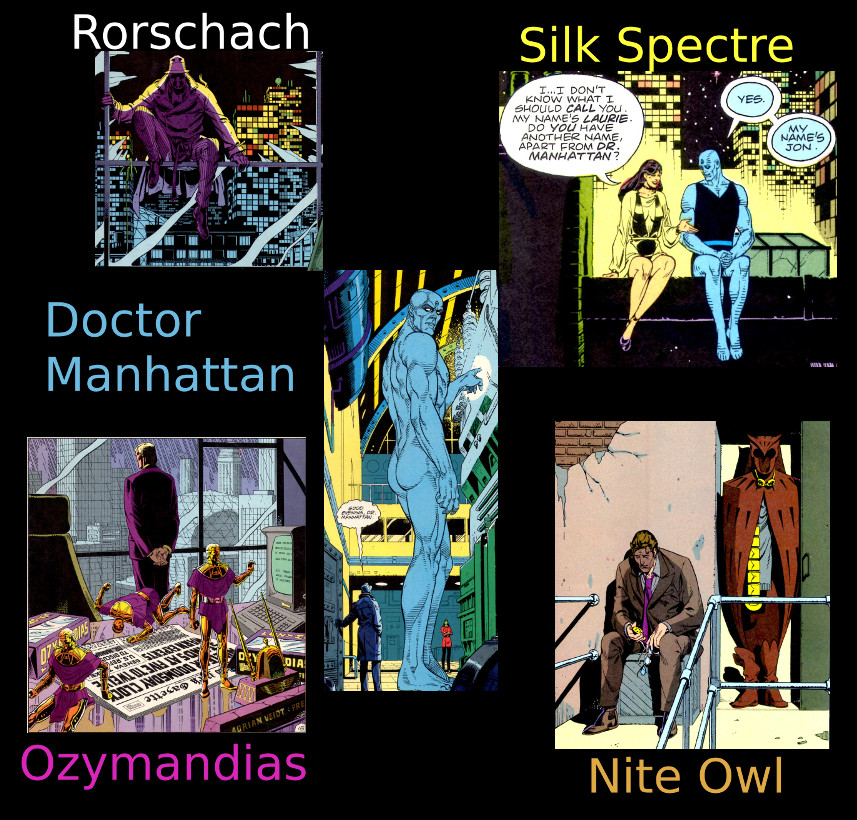

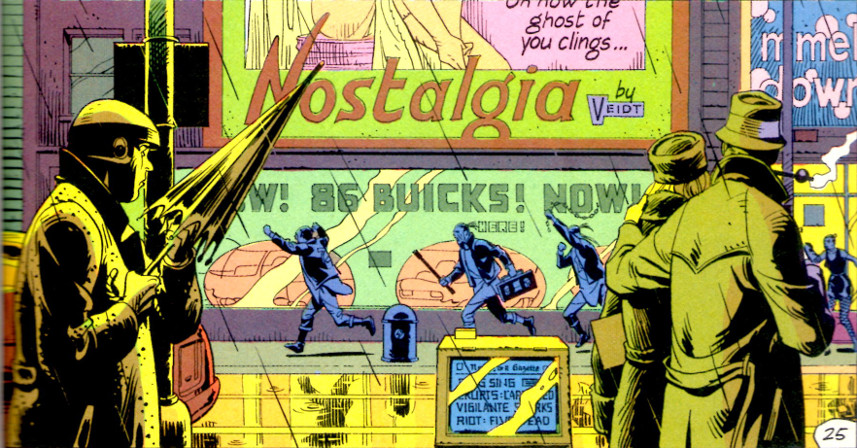

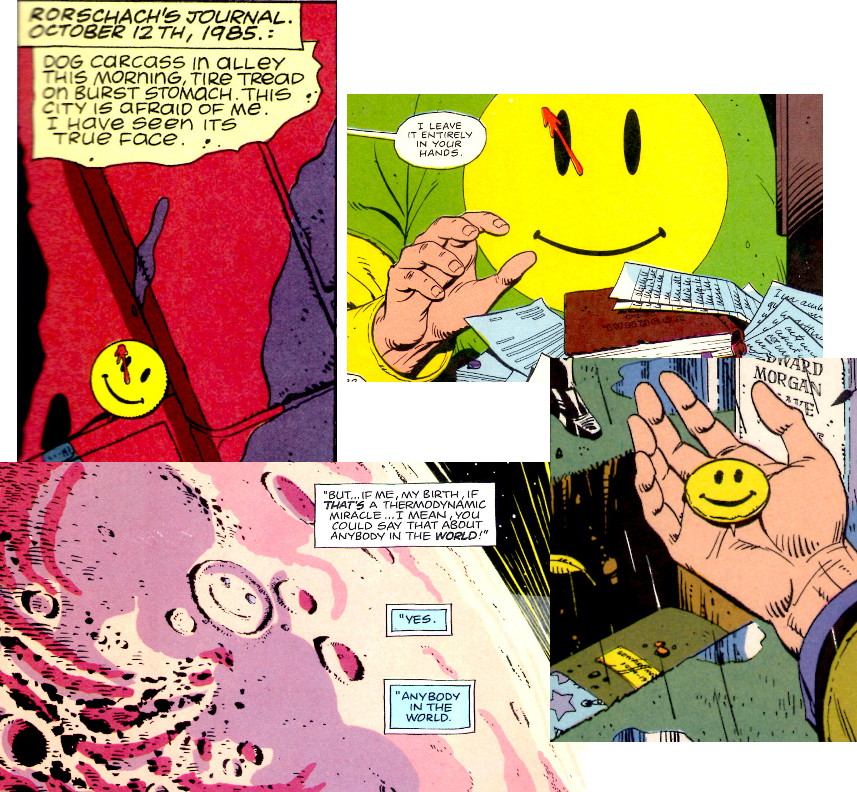

Whether this latter move was to save face by implying the NU was never meant to last or whether it was acknowledgment that all of the NU titles had transformed from their original intention, the implication was quite clear. The writing and editorial staff recognized that what had started as an open organic universe had, by the action of many outside forces, become one of the largest architecturally-structured crossover events attempted. As a result, the New Universe ended up having a sprawling internal consistency absent from the larger universes of DC and Marvel. This consistency gave it a feeling more like a set of vignettes in a larger novel rather than a set of titles set in a shared universe. It is not hard to see similarities to the structure, size, mood, and feel found in Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, which is a huge graphic novel (over 2000 pages) of how metahuman presence in the world triggers global war and subsequent disasters. (Note that this was a common theme of the 1980s and it formed the backbone for another sprawling graphic novel of that time, The Watchmen.)

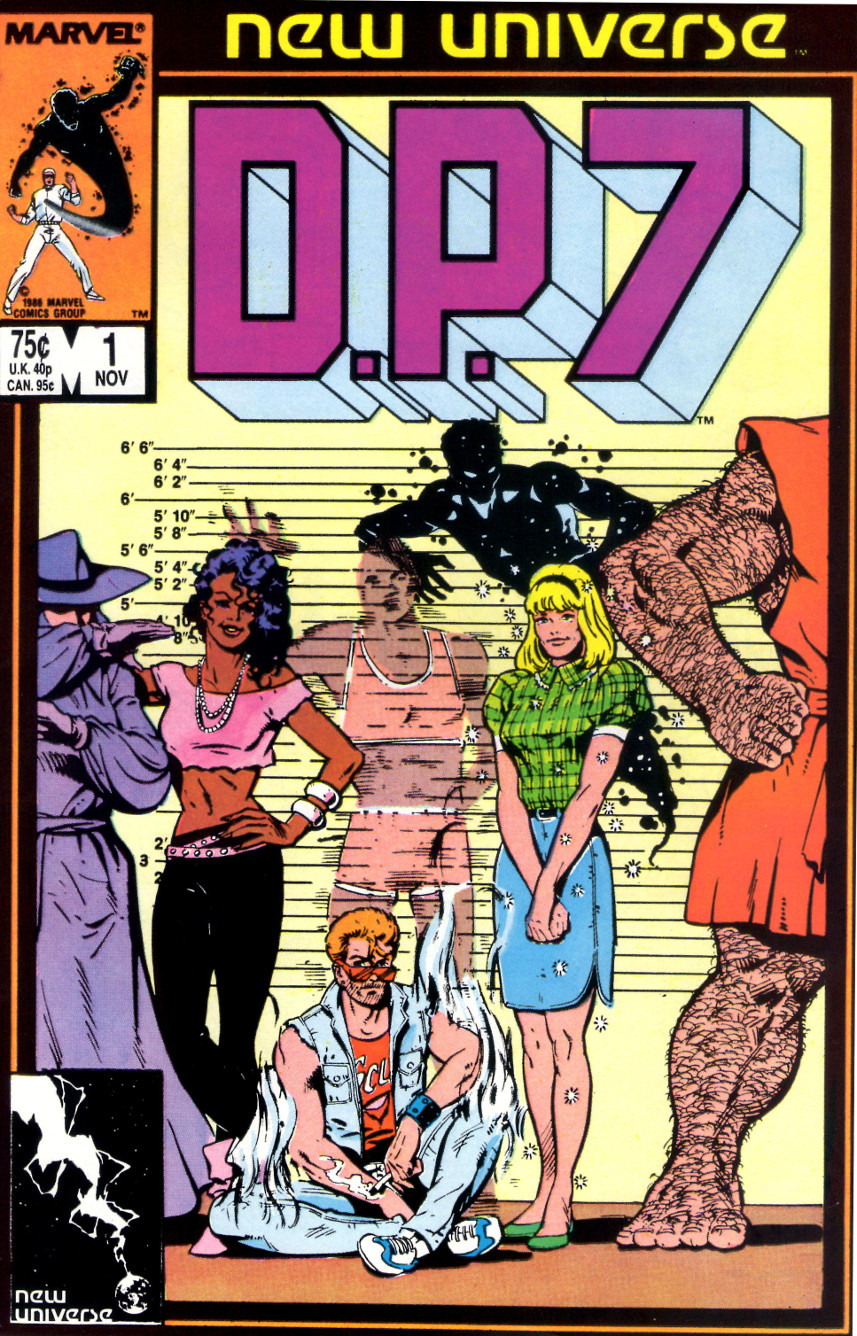

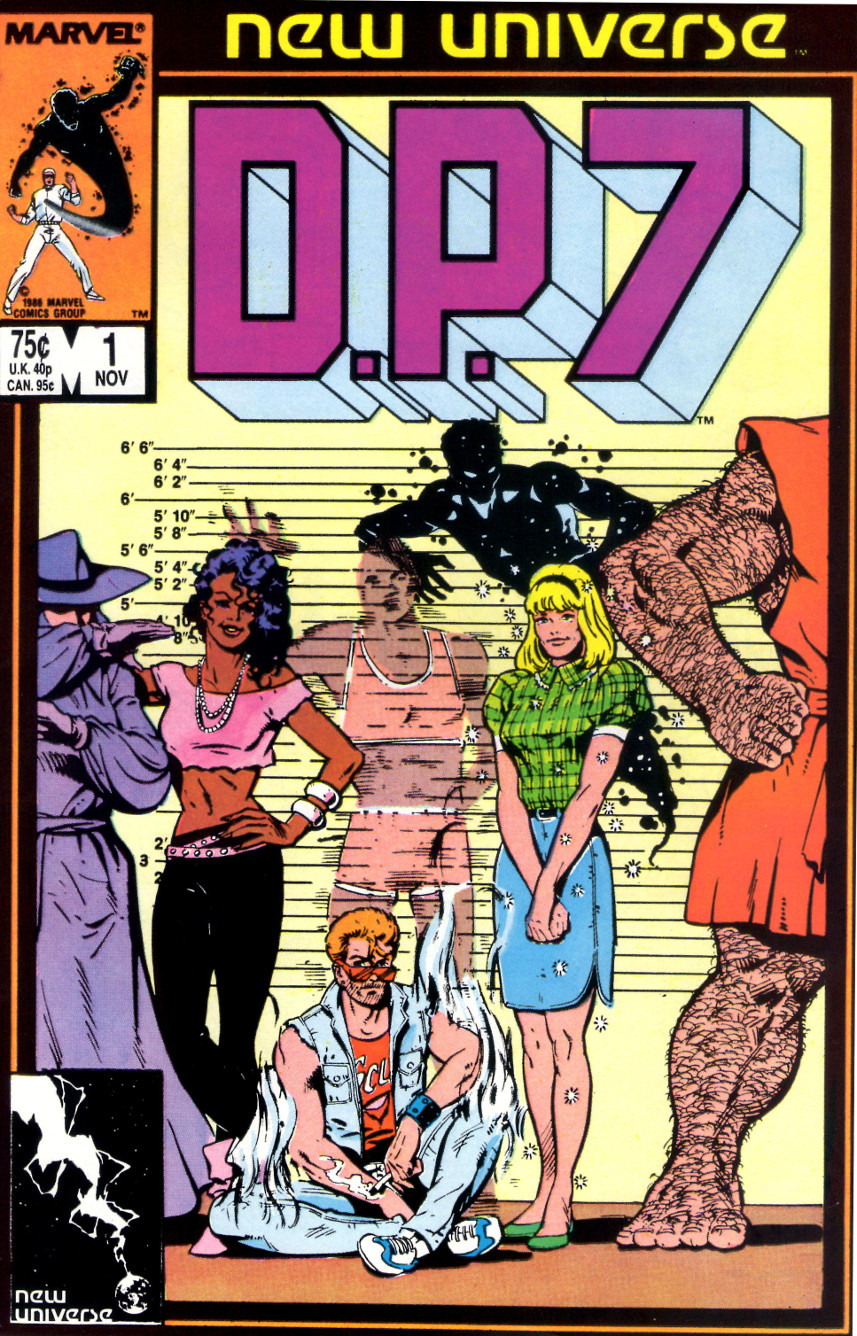

D.P. 7 (32 Issues & 1 Annual)

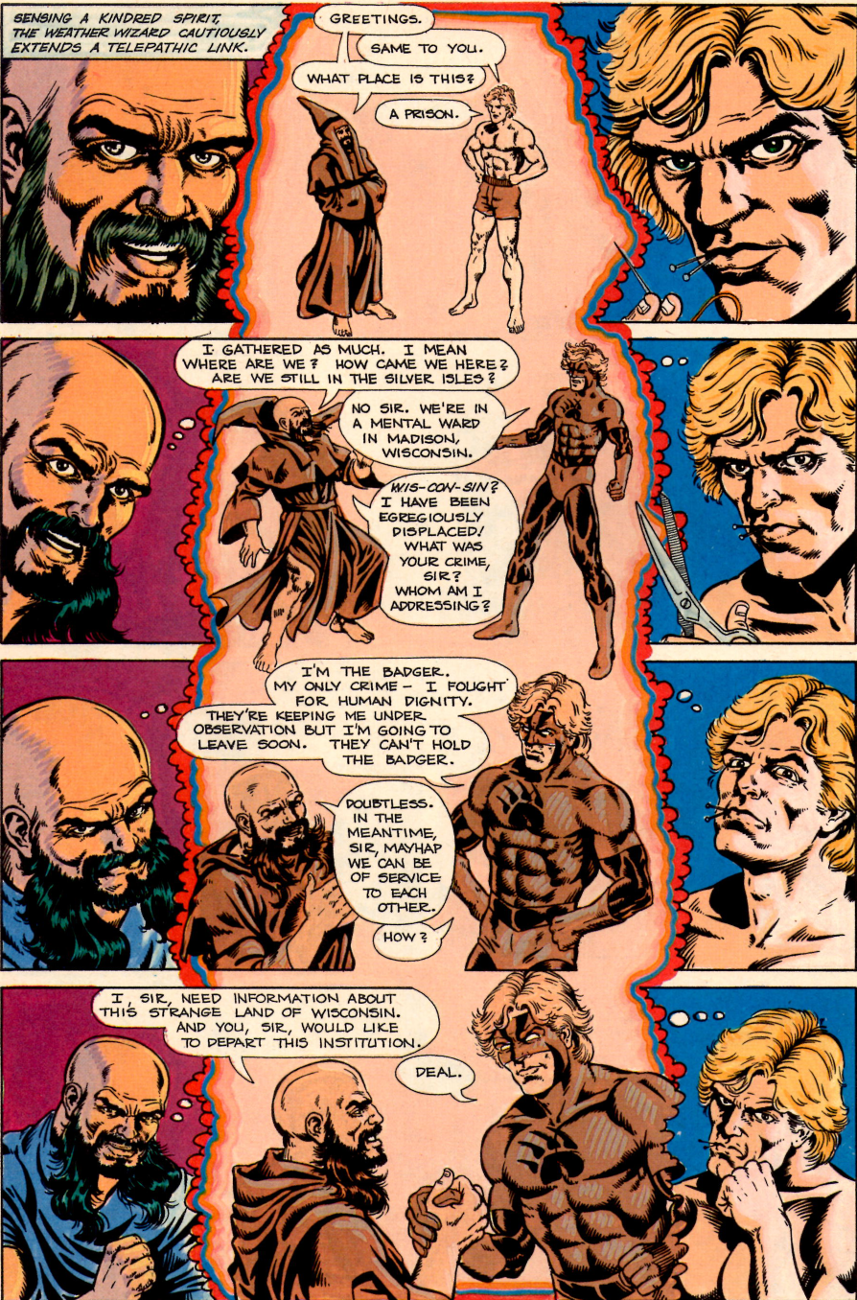

Certainly the most stable of the long series runs was D.P.7, which was an abbreviation for Displaced Paranormals 7. The brainchild of Mark Gruenwald, who wrote every issue, the series followed the fate of various individuals who were one day normal humans and the next day transformed by the White Event into paranormals.

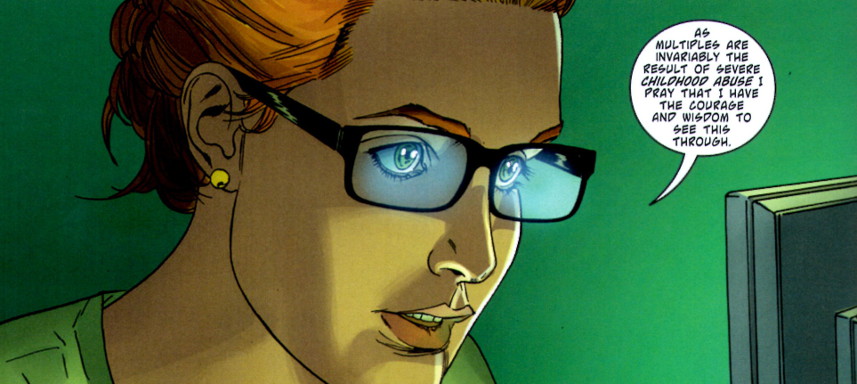

Much of the initial story centers around an institution set in the back woods of Wisconsin with the name of Clinic for Paranormal Research, or the Clinic for short. Each of the original D.P.7 team members has come to the clinic to get ‘treatment’ for their unique paranormal ability. Unbeknownst to them, the Clinic is run by an incredibly powerful paranormal, Philip Nolan Voigt, who had used his equally powerful wealth to assemble a staff of like-minded paranormals to help him develop, mold, and eventually control his own private army of super-powered humans.

Becoming aware of Voigt’s intent, seven of The Clinic’s patients band together and flee. Hounded by the Clinic’s paranormal hunters, the group has many adventures as they try to figure out how they fit together with each other and society as a whole. Eventually, they are recaptured by the Clinic, but manage to seemingly defeat Voigt (issue #12).

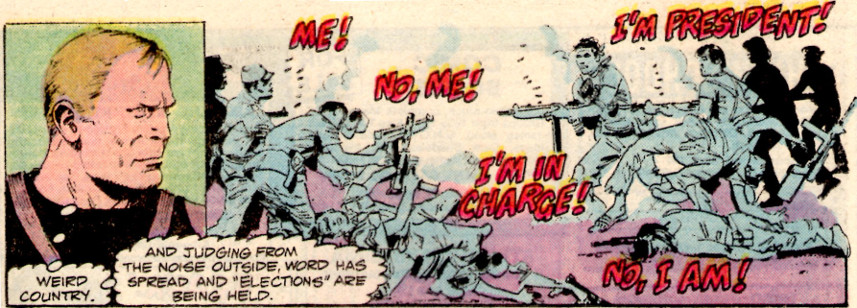

Now free of the main villain that kept both the team (and the plot) united, the D.P. 7 team begins to fracture. The Clinic becomes a self-governing paranormal institution and it doesn’t take long before internal politics turns the situation into something more befitting The Lord of the Flies, as various loyalties begin to split along demographic lines (African-American paranormals versus teenage paranormals versus…). Before long it is paranormal against paranormal in full-scale donnybrooks.

The situation changes when the destruction of Pittsburgh happens (see Star Brand & The Pitt below) and the government begins to recruit paranormals while global tensions rise and war with the Soviet Union seems certain. Once again finding themselves united against a common foe, the paranormals battle official forces

in a desperate attempt to remain on their own. Despite these efforts, many of the women are pressed into service with the CIA and many of the men are conscripted for the Army’s paranormal division.

The series enters into its third and final arc, which shows the consequences of military/government service and the aftermath. In the final couple of issues, a unique paranormal, called the Cure, becomes the focal point. True to his name, the Cure is able to undo the paranormal transformation in anyone who wants to be ‘normal’ again, and the series ends with a bit of closure as many of the most tragic figures go back to being human.

Overall, the series tried from the onset to be ‘real-world’, although it often failed to match Shooter’s original vision of a muted approach to the fantasy/science fiction and the hope that passage of time in the title would match that of our world. The themes explored were mature, with religion, racial tensions, and overall alienation central to the plots.

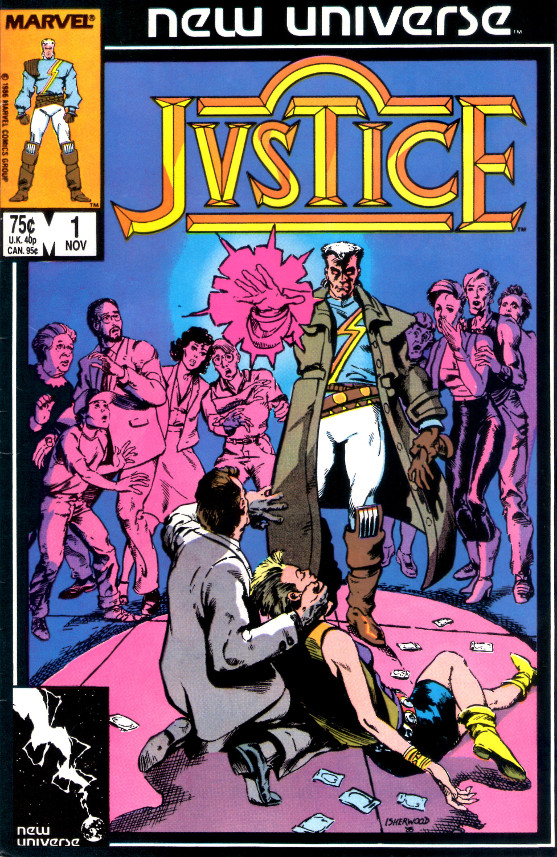

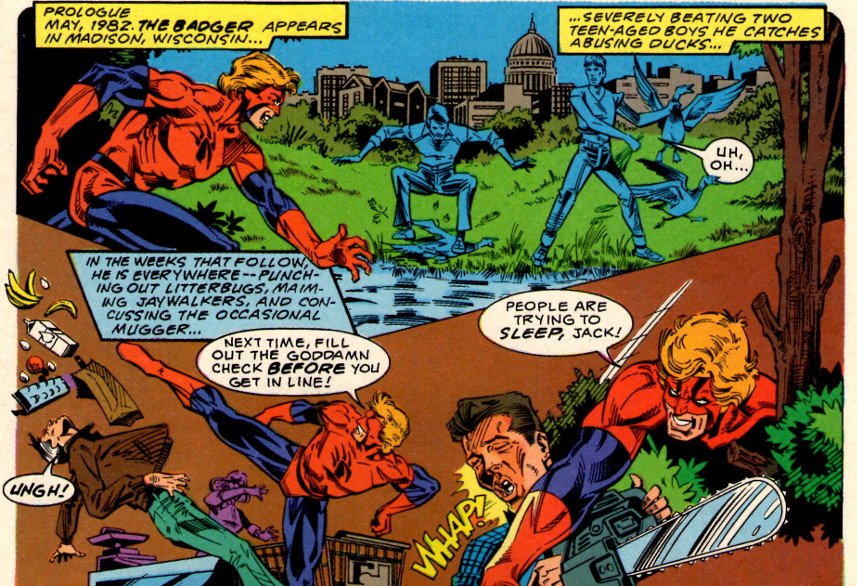

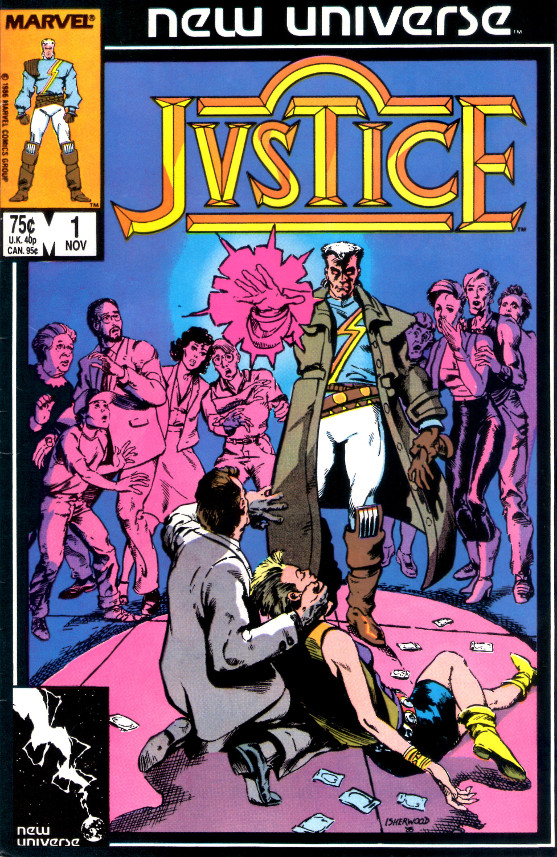

Jvstice (32 Issues)

Jvstice is the one outsider from the set of NU long-running books. In the beginning, the lead character was a Justice Warrior called Tensen who came from a magical other dimension. Tensen had been exiled to Earth and was seeking an evil wizard by the name of Darquill, who was using the drug trade in our dimension to build up power in order to destroy Tensen’s people.

Tensen was very much visualized as a product of the 1980s with balloon pants, futuristic shades, and a Flock of Seagulls haircut.

Not only did his clothes seem over the top, the fantasy-based magic theme was completely at odds with the core NU concept. Matters were made worse by the fact that no stable creative staff materialized – 6 writers and 6 artists in the first 14 issues – and by the wandering storyline that continuously waffled in its portrayal of Tensen as victim, sinner, or hero.

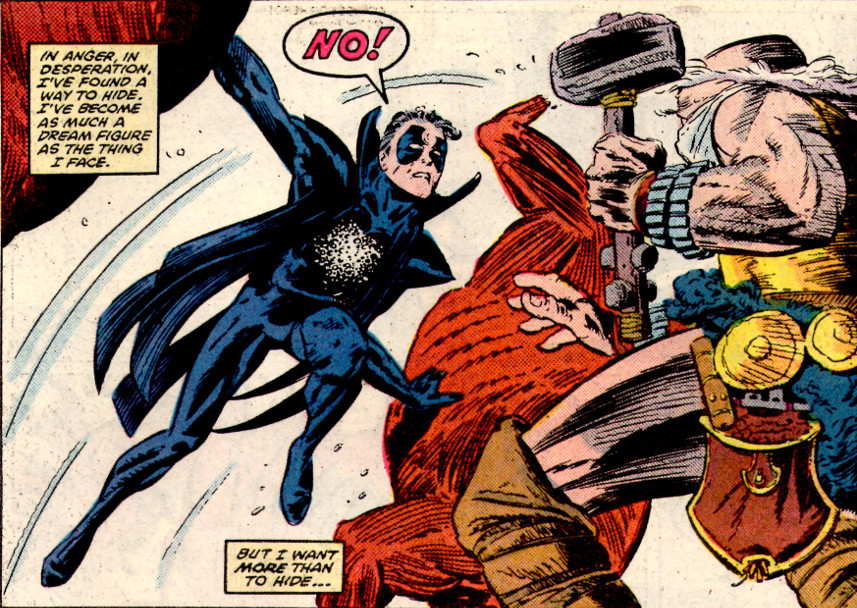

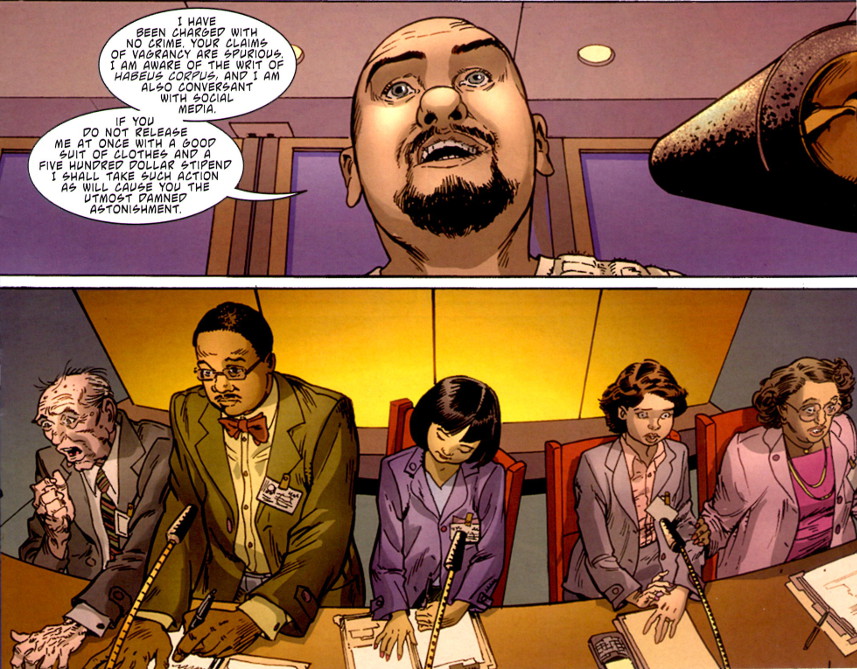

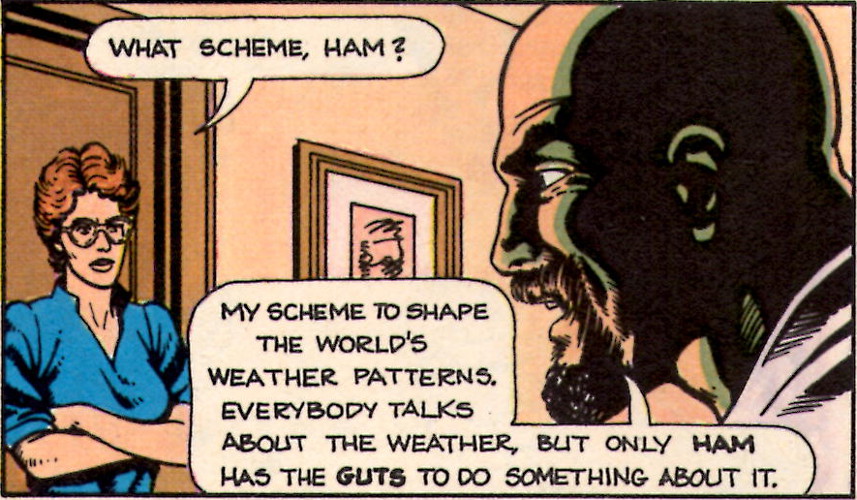

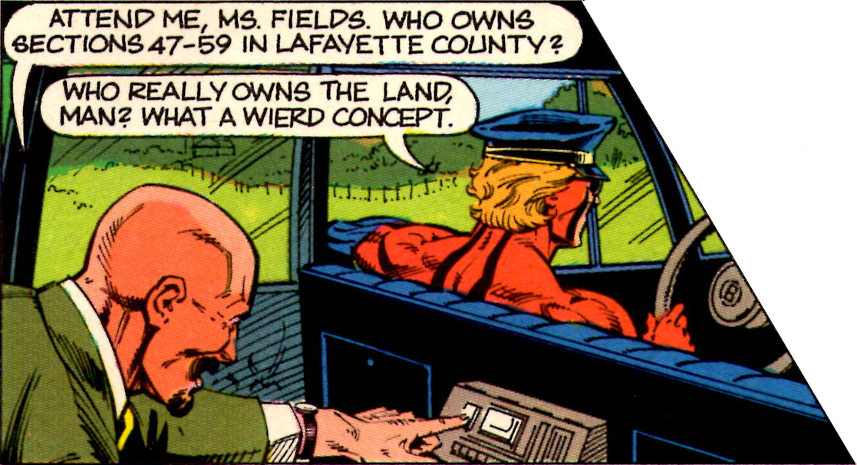

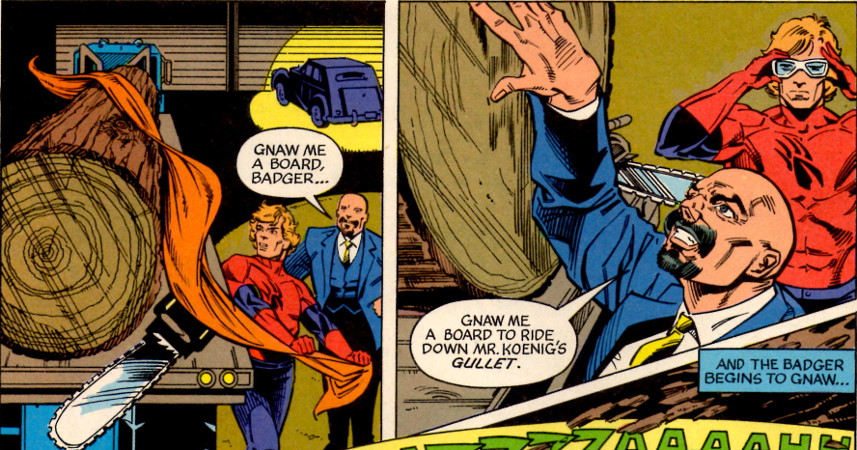

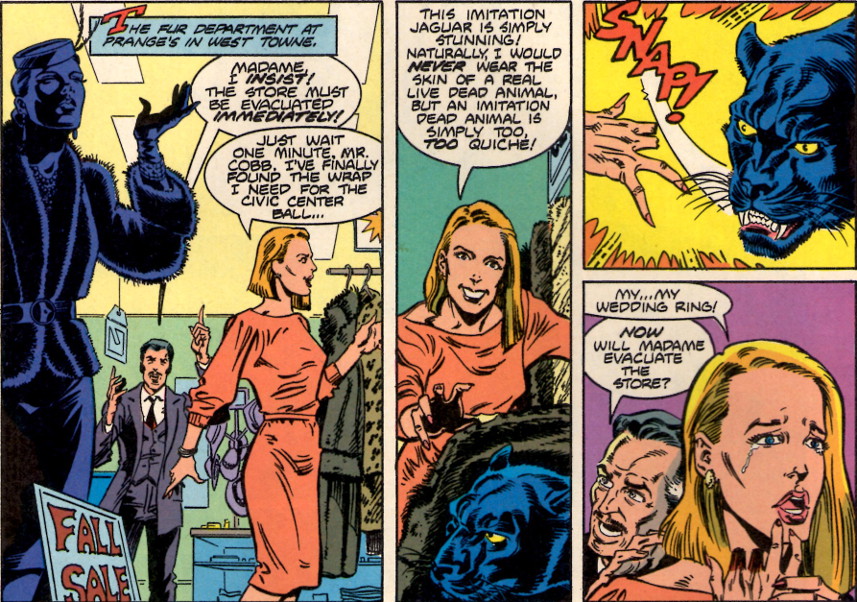

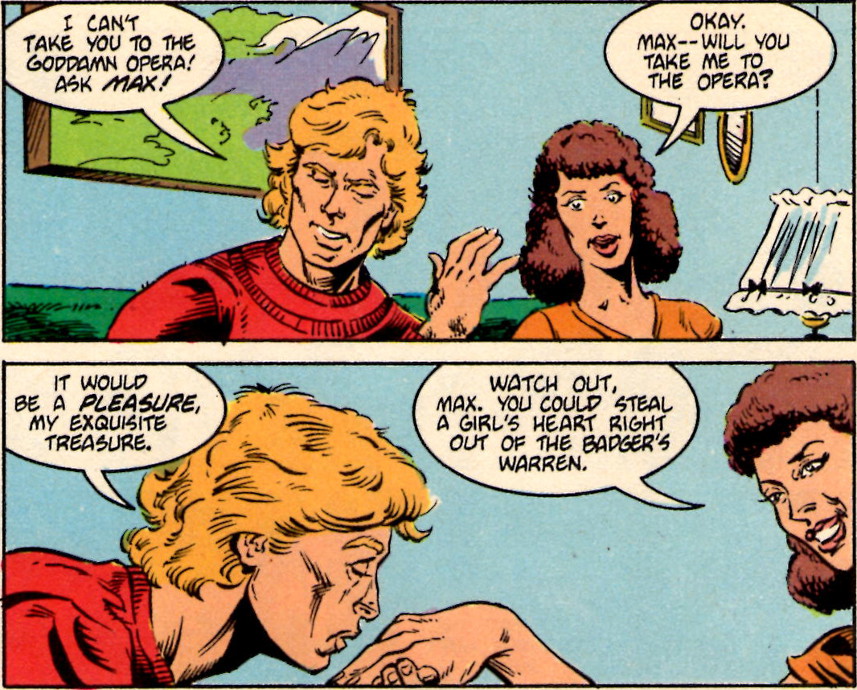

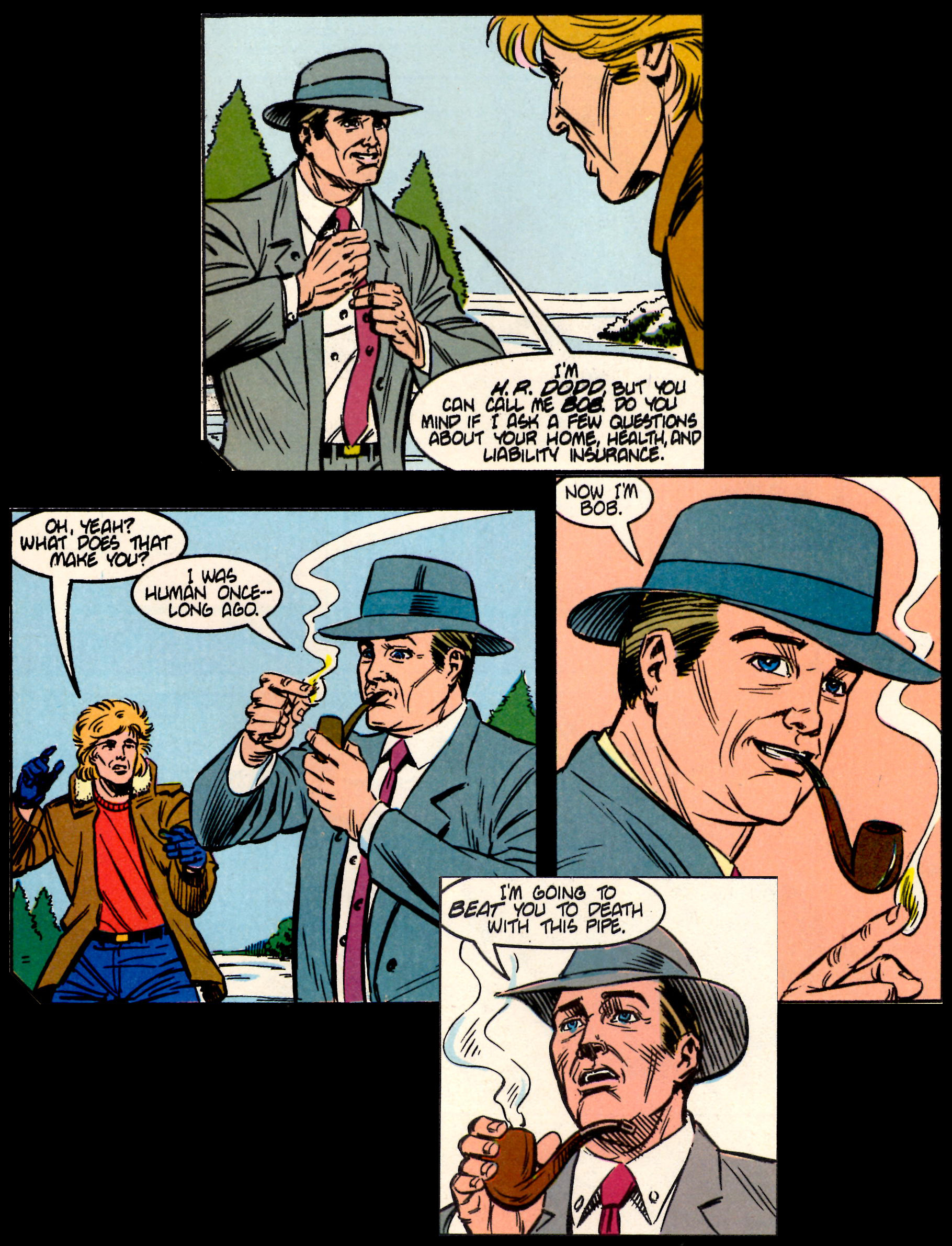

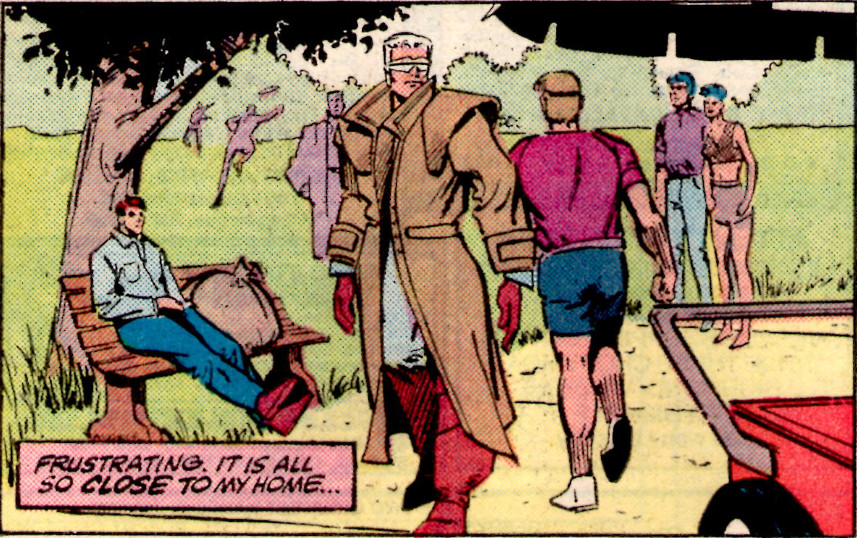

Fortunately, the last change happened when Peter David took over the writing chores on issue #15. He retconned the entire series motif in one fell swoop by transforming Tensen Justice Warrior into John Tensen, undercover officer in the Department of Justice. He explained away the magical aspects of the first year by making them a by-product of a psychic struggle between officer Tensen and the drug kingpin Daedalus Darquill, both of whom acquired psionic powers after the White Event.

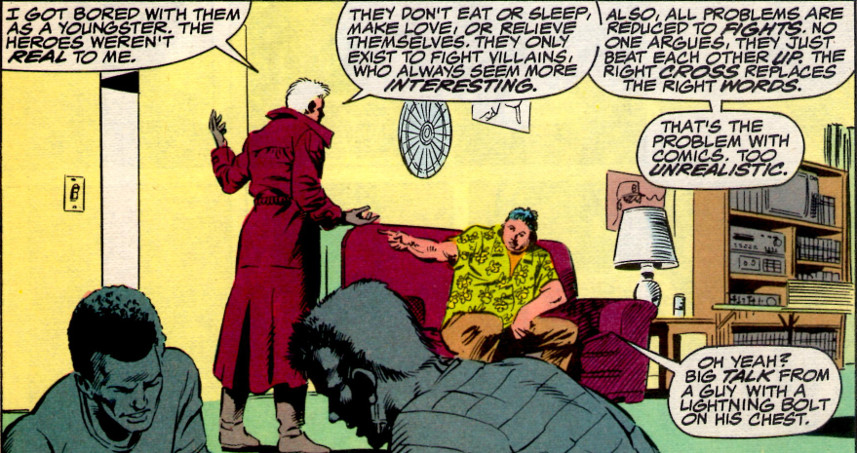

From this point on, David’s clever plots and skillful dialog changed the entire tenor of Jvstice, placing it firmly as the best offering from the NU. A brilliant sample of his approach is captured in the following exchange between Tensen and another character about comic books

Mindful of his audience, David provides a nice closure for the series in issue #32 with Tensen becoming a just ruler of a paranormal community located on Coney Island, of all places.

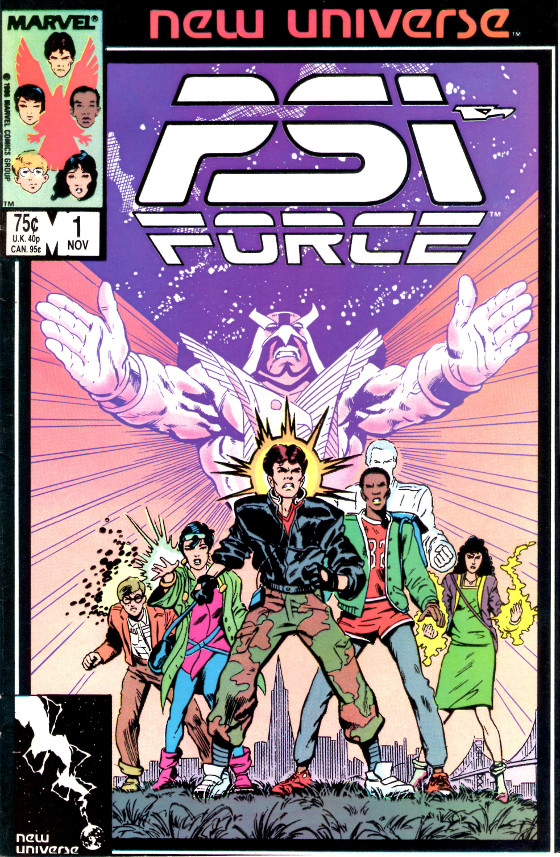

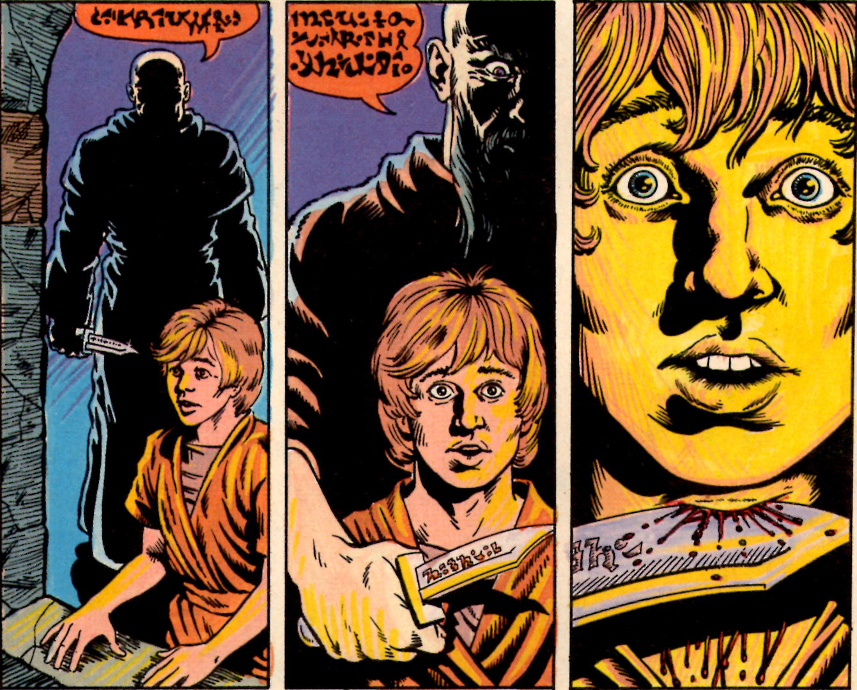

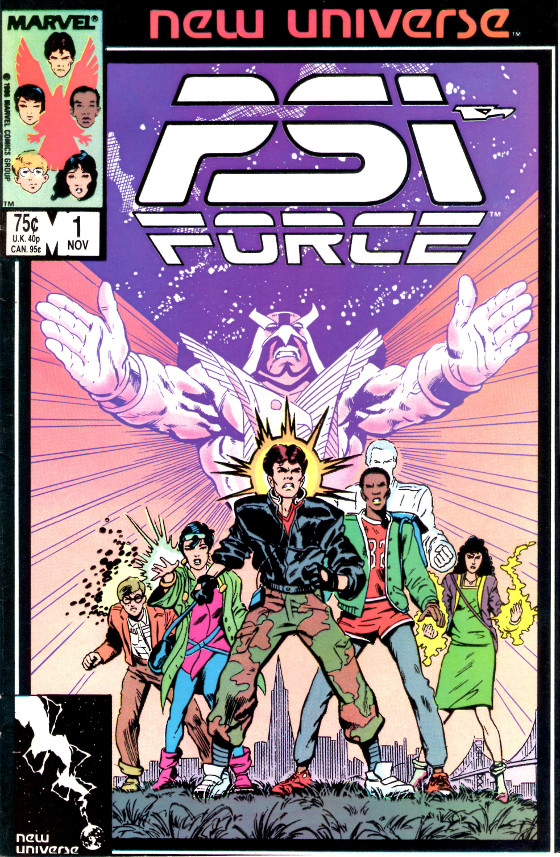

Psi-Force (32 Issues & 1 Annual)

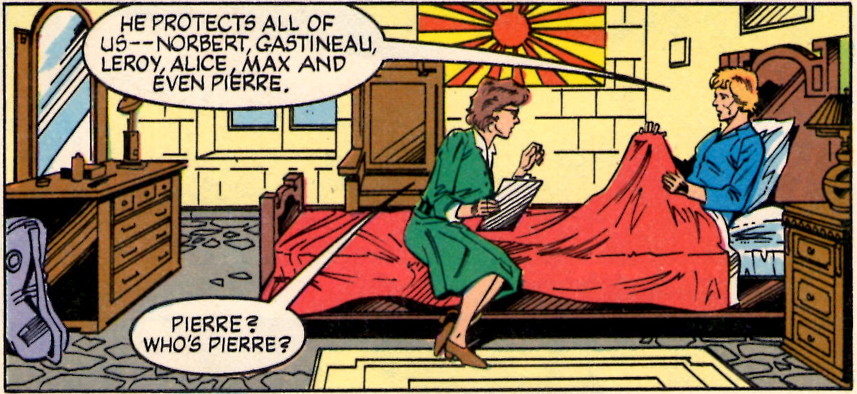

The least interesting of the bigger titles, Psi-Force follows the ups and downs of a team of paranormal teenagers from different countries and walks of life.

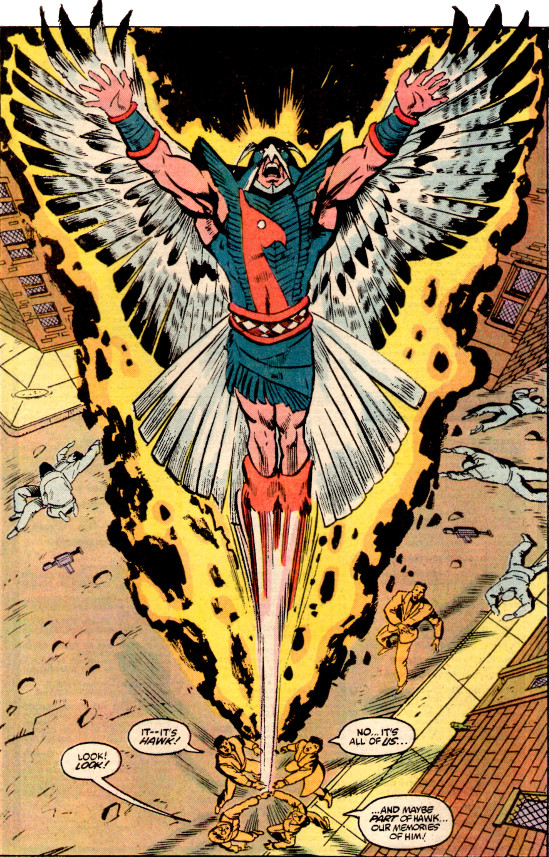

Aside from their paranormal abilities, the only other commonality was that the core team was limited to 5 individuals. The reason for this is that federal agent Emmett Proudhawk, himself a paranormal, brought the team together because of a dream he had,

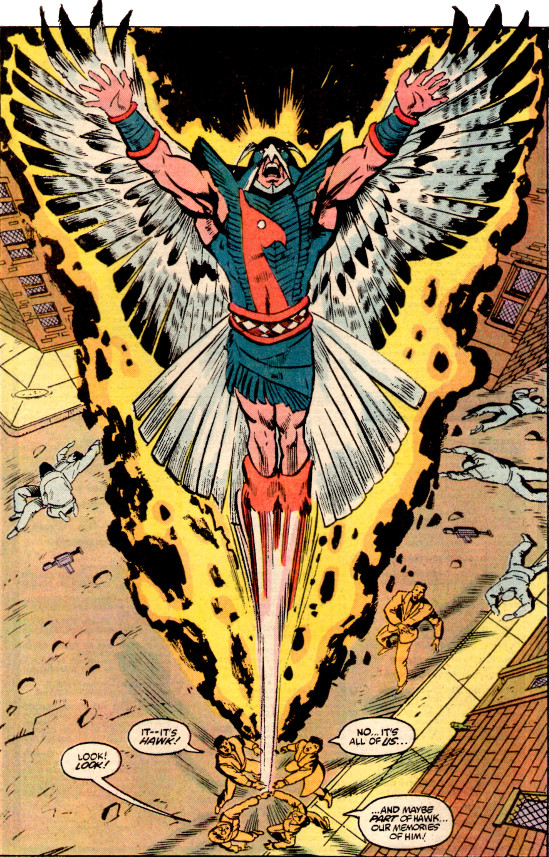

in which he foresaw that the powers of each team member could be merged into an immensely powerful entity called Psi-Hawk.

Fewer than 5 members caused Psi-Hawk to be too weak and greater than 5 drove it mad with power. In this way, the Psi-Force writer could regulate membership in the team and, presumably, simplify story creation.

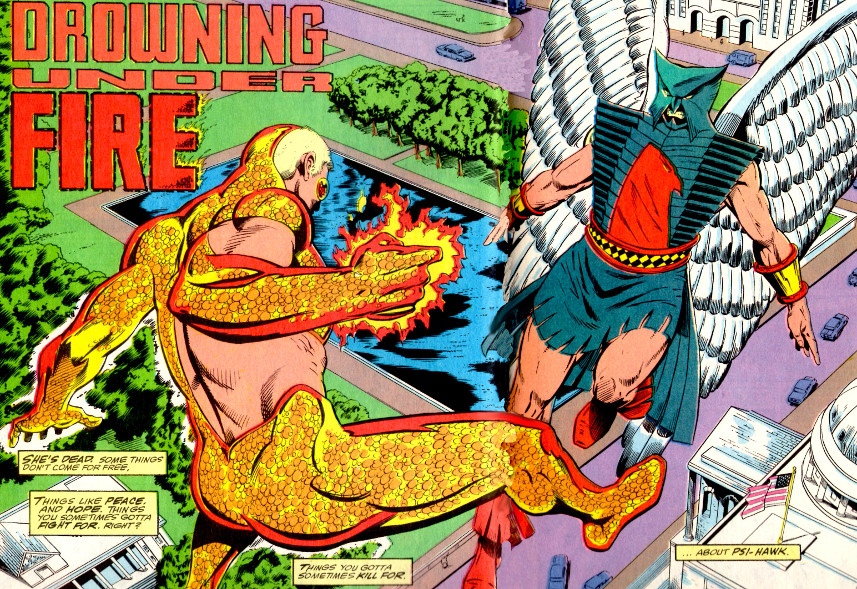

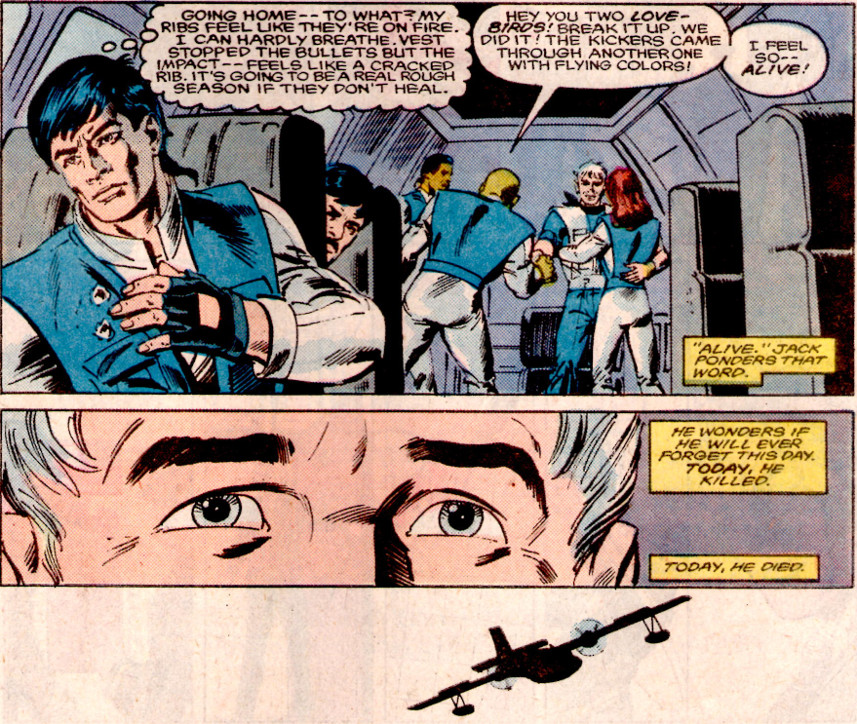

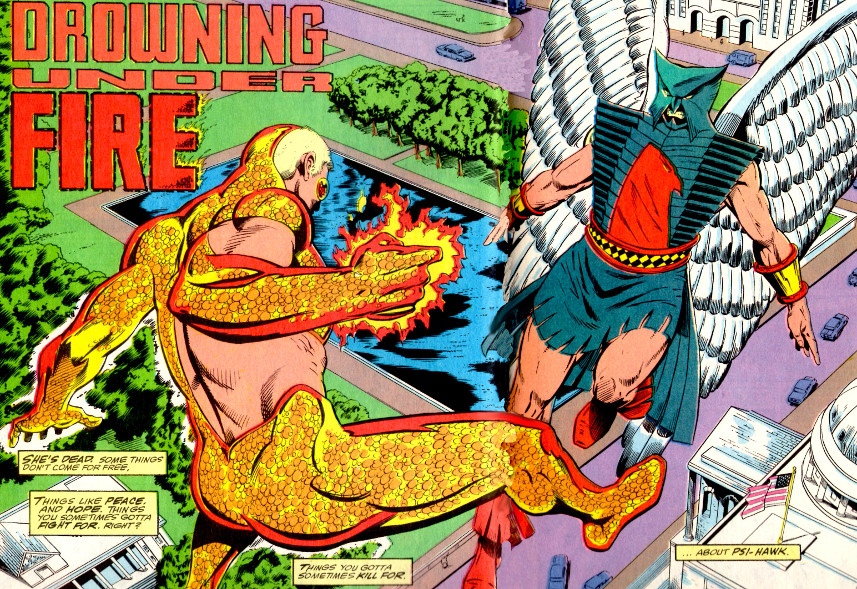

The entire run is generally unremarkable from a narrative point of view, with the team implausibly transitioning from scared teenagers to secret agents in a matter of a couple of years. Nonetheless, it has some of the best art of any of the NU titles

and some of the more interesting, if horrific, deaths for some of its characters.

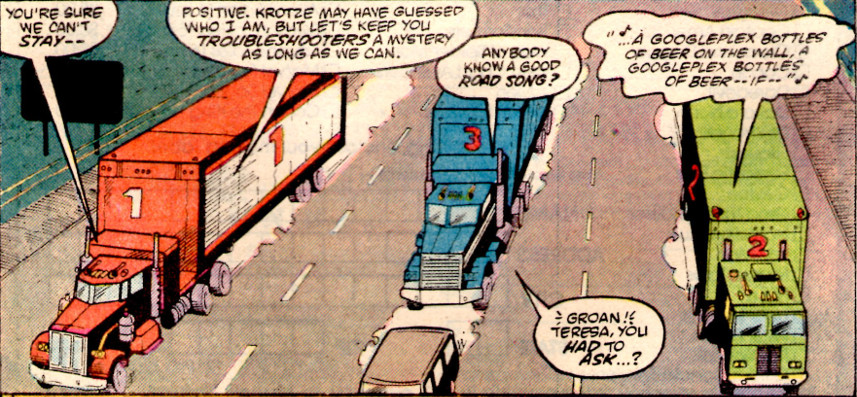

At the end of its run, the core 5 members have joined into a loose alliance with the Medusa Web, a paranormal mercenary group, before riding into the sunset for some R&R.

Star Brand (19 Issues & 1 Annual) & The Pitt/Draft/War

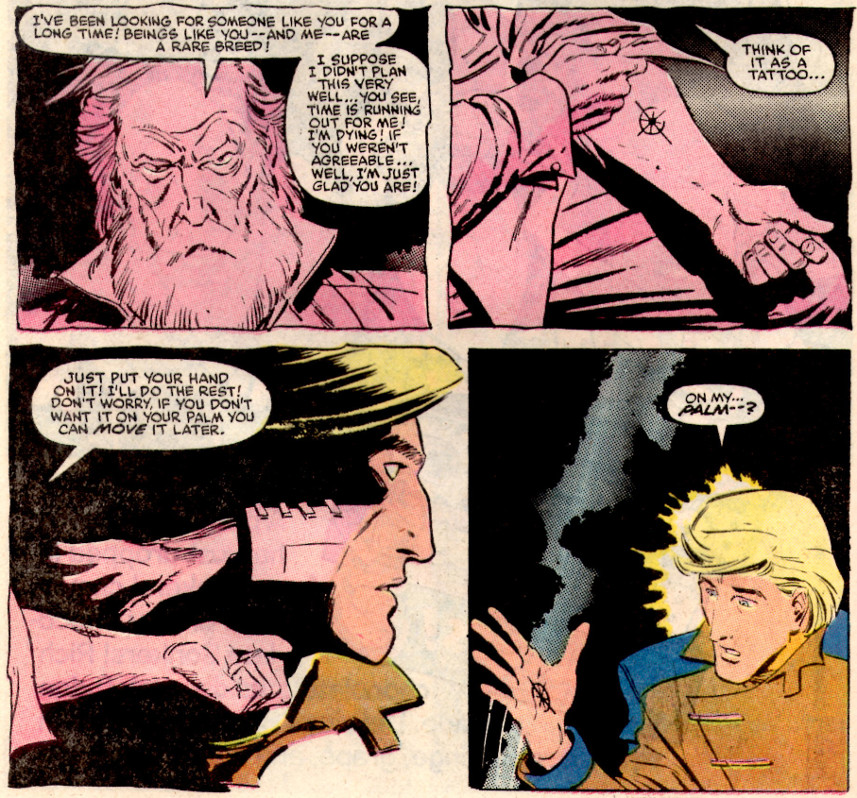

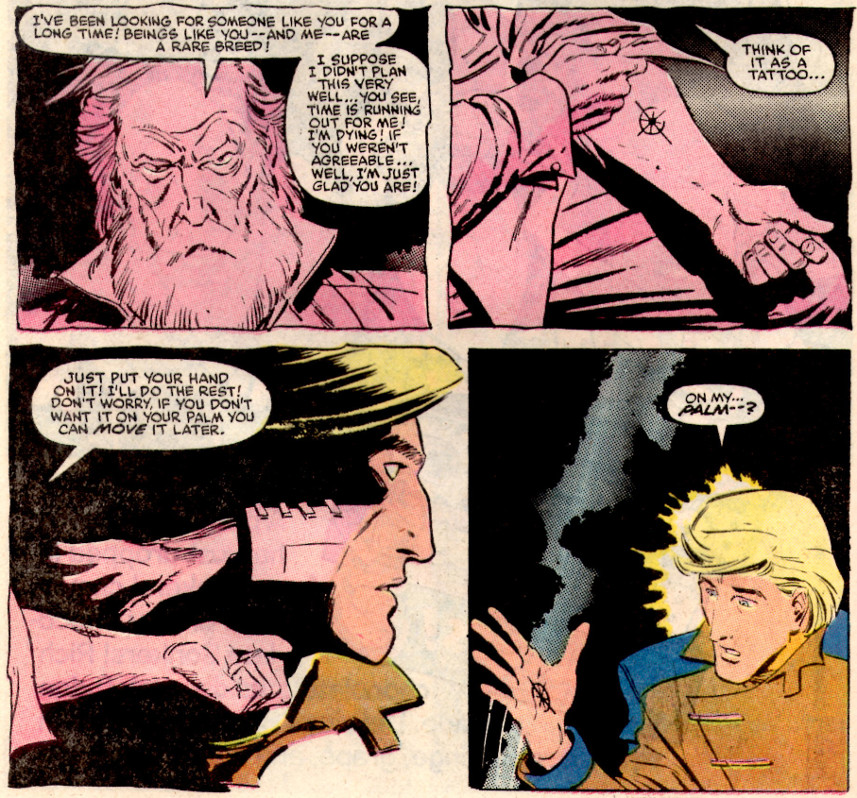

The final entry into the NU titles that made it through the whole duration of the imprint is Star Brand,

which follows what happens to Ken Connell, a Pittsburgh auto mechanic, when he receives a weapon of surpassing power called the Star Brand from a mysterious old man.

With the Star Brand, Connell is essentially unstoppable, as long as he concentrates and keeps his emotions in check. He soon realizes that having this much power isn’t as easy as it seems and that real world problems can rarely be solved by bludgeoning something or somebody. He begins trying to think rather than punch through the challenges that face him. This theme, which lasts mostly for the first 6-10 issues, is truest to the original NU concept of real-world consequences of having super powers and for good reason – Jim Shooter was the writer for the first 6 issues.

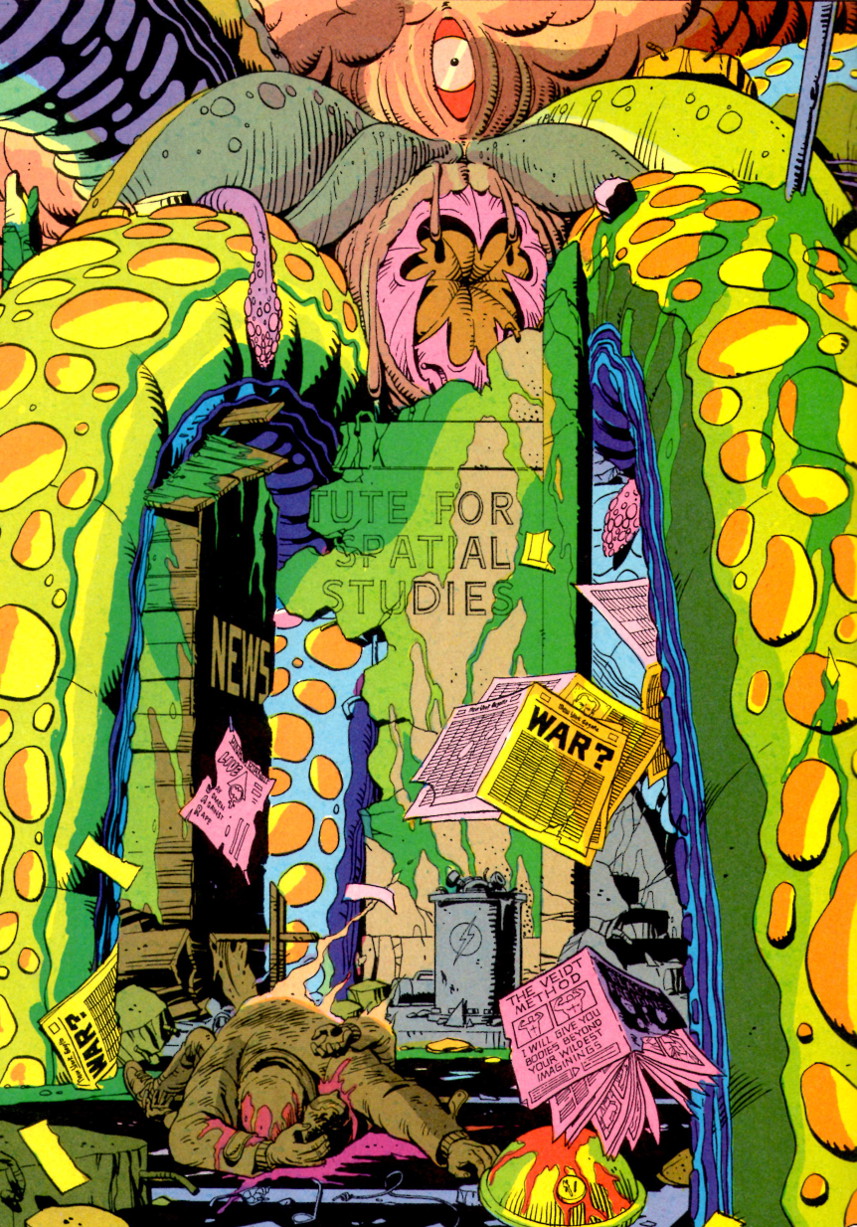

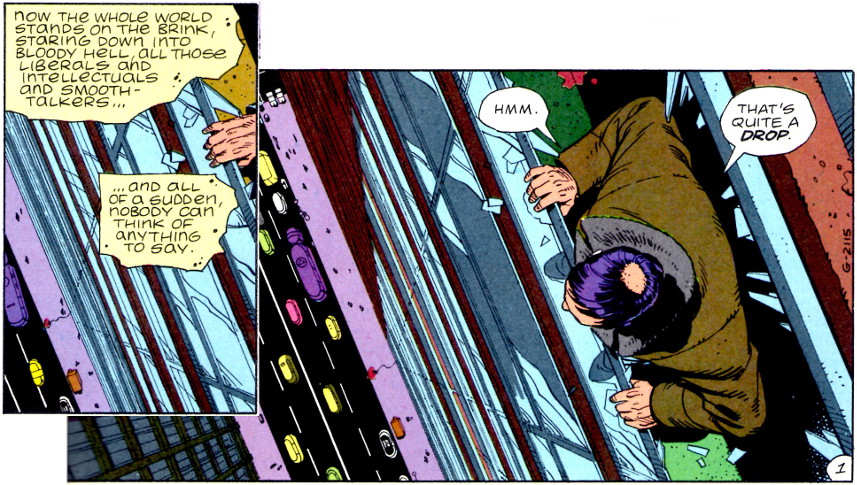

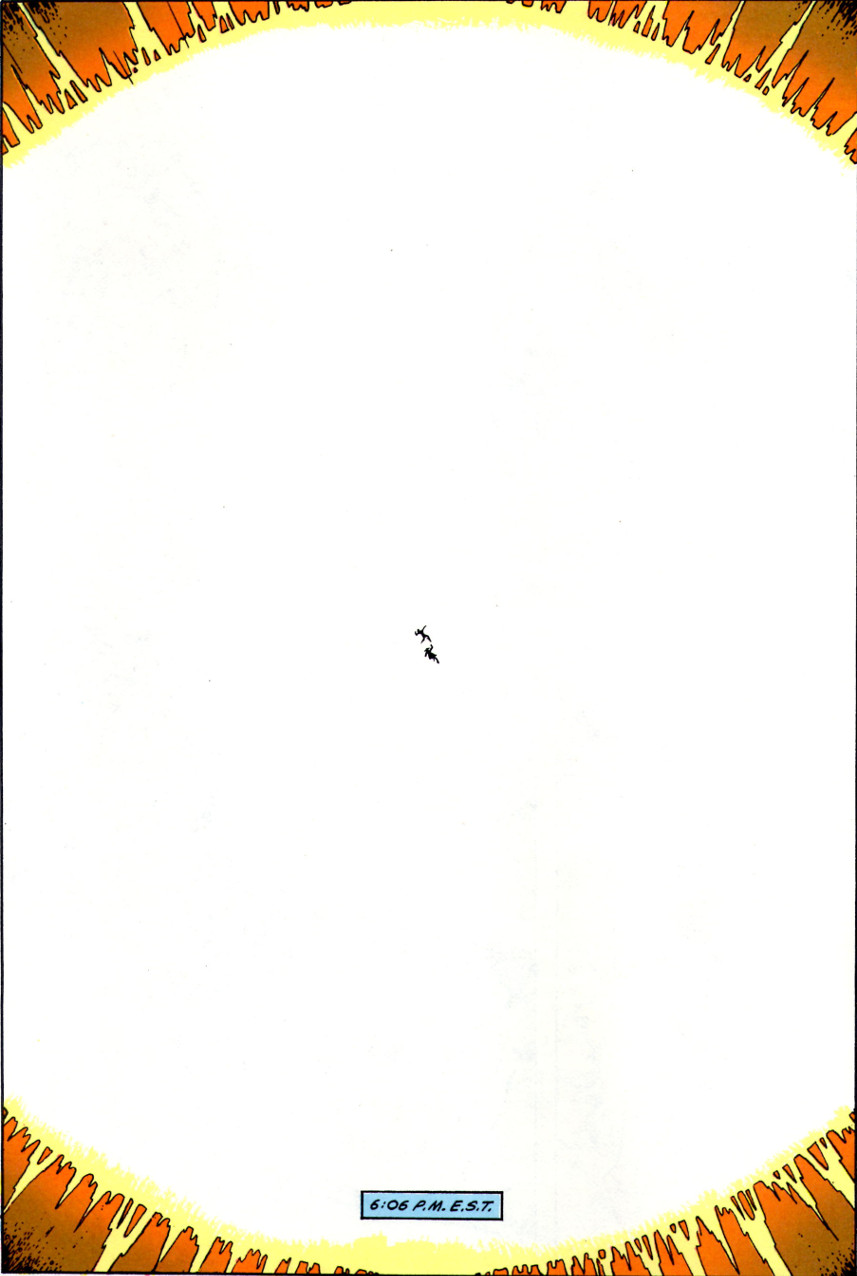

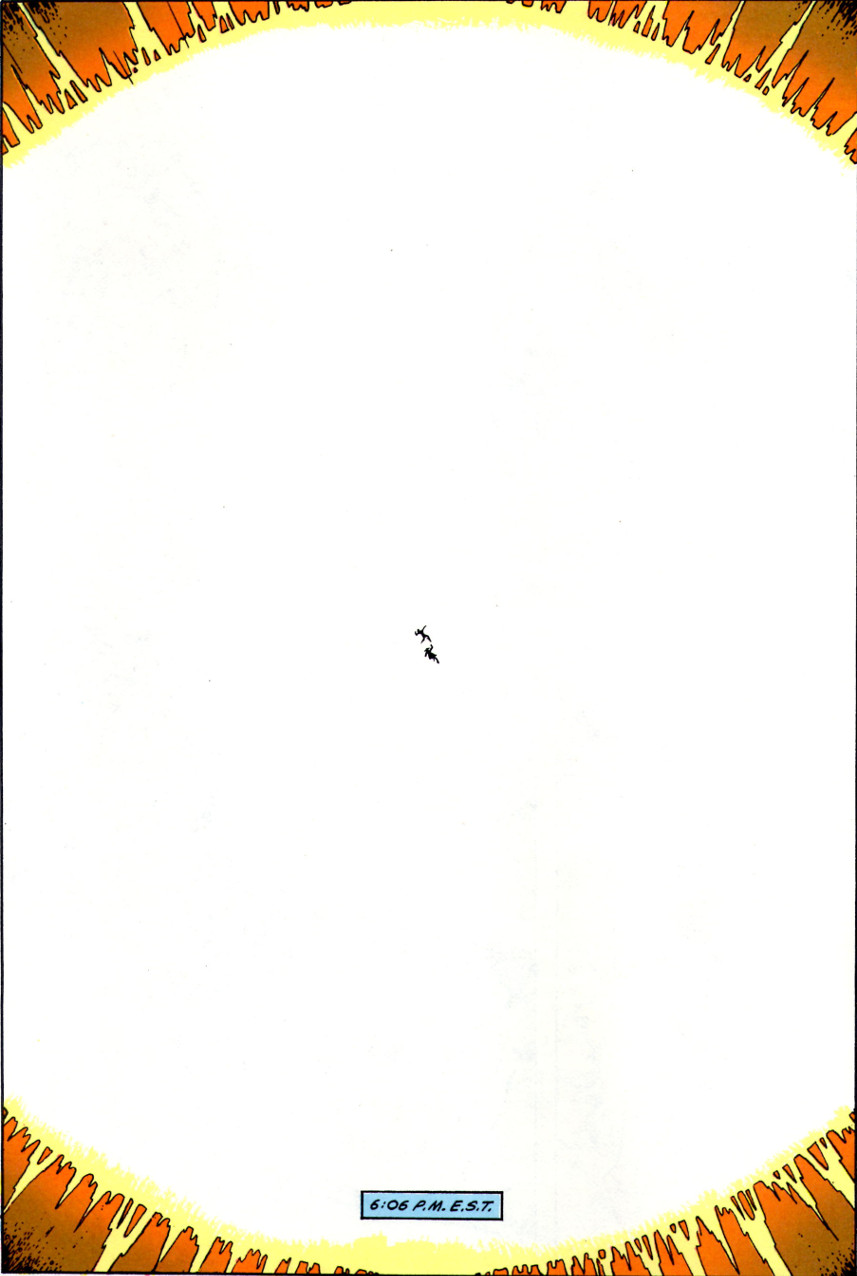

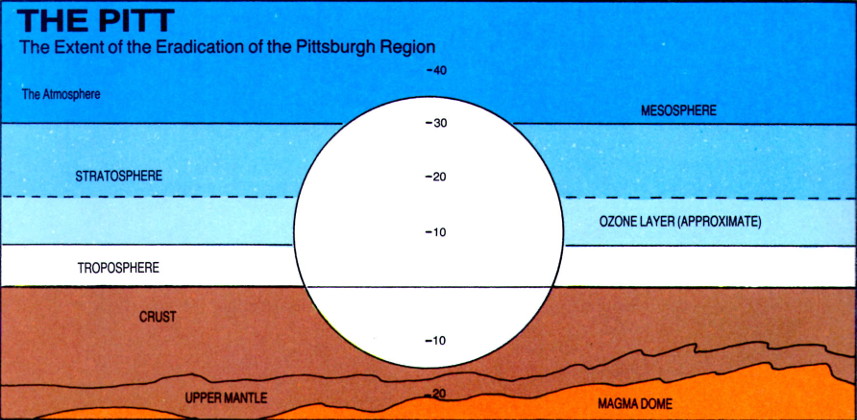

Shooter’s influence is abruptly erased when John Byrne takes over the chief creative role on Star Brand. Byrne’s first action is to have Connell become dejected with the Star Brand and attempt to transfer the brand to a dumbbell. The result is the immediate destruction of the city of Pittsburgh in a ball of light reminiscent to the destruction of Tokyo in Akira

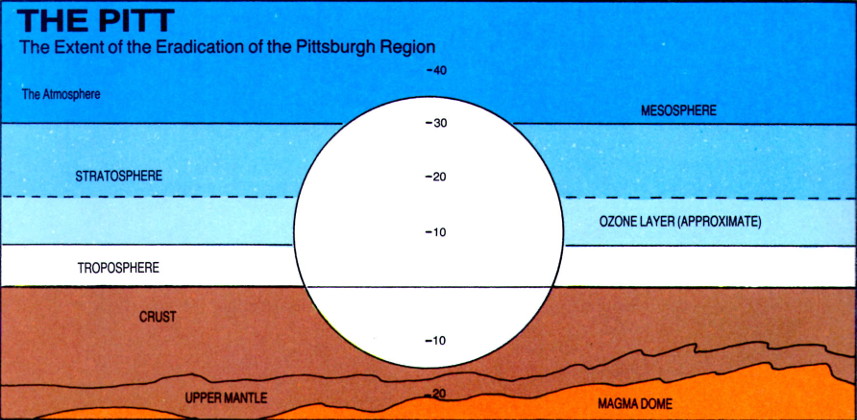

The destruction of Pittsburgh, which is mostly the subject of The Pitt one-shot, is the trigger event for the World War III scenario that tied the NU titles together from that point onward. Thinking the destruction had been caused by a nuclear explosion, tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union come to a fever pitch. Both sides recruit and train paranormals for the eventual conflict as covered in The Draft one-shot and ongoing issues of D.P.7 and Psi-Force.

The remains of Pittsburgh and surrounding areas, now known as the Pitt,

become capable of mutating anyone exposed to the materials and energies at play. The Pitt becomes an additional source of paranormal manifestations, including the transformation of Jenny Swensen into an organic metal woman.

Overcome by guilt, Connell retreats from the world in depression and insanity. His son, who received the power of the Star Brand at his conception, grows at a rapid rate, becoming an adult known as the Star Child (with no apologies or credit given to 2001) within a year of his birth.

The Star Child intervenes, in a messianic fashion, and stops the war between the US and the USSR (as chronicled in The War limited series)

before going on to try to clean up the real source of damage and danger, the Star Brand.

It seems that the White Event, which brought paranormal powers world-wide, was caused when the mysterious old man, now simply called the Old Man, tried to transfer the brand to an asteroid. Inanimate objects are ill-suited for the power of the brand and they detonate with a burst of energy that can mutate and transform every living creature caught in their path. The Star Child also realizes that the Old Man, and Ken, and himself are all three aspects of the same man.

In order to save the universe, the Star Child insists that Ken needs to go back in time to become the Old Man, he needs to go back in time to become Ken, and, presumably, the Old Man also goes back in time to become the infant Star Child. Of course, this makes absolutely no sense, and Byrne’s job of explaining this is badly flawed as almost all time-travel stories are.

It is ironic that the one title in the New Universe imprint which started out most faithfully following the NU concept that paranormal abilities come with real-world consequences should end with, arguably, one of the biggest deus ex machina moments in all of comics history.