This week, I start my review of the approach to creating comics authored by Alan Moore. An earlier column touched upon Moore’s approach as viewed through the lens of Neil Gaiman, who claims to have learned his technique directly from Moore.

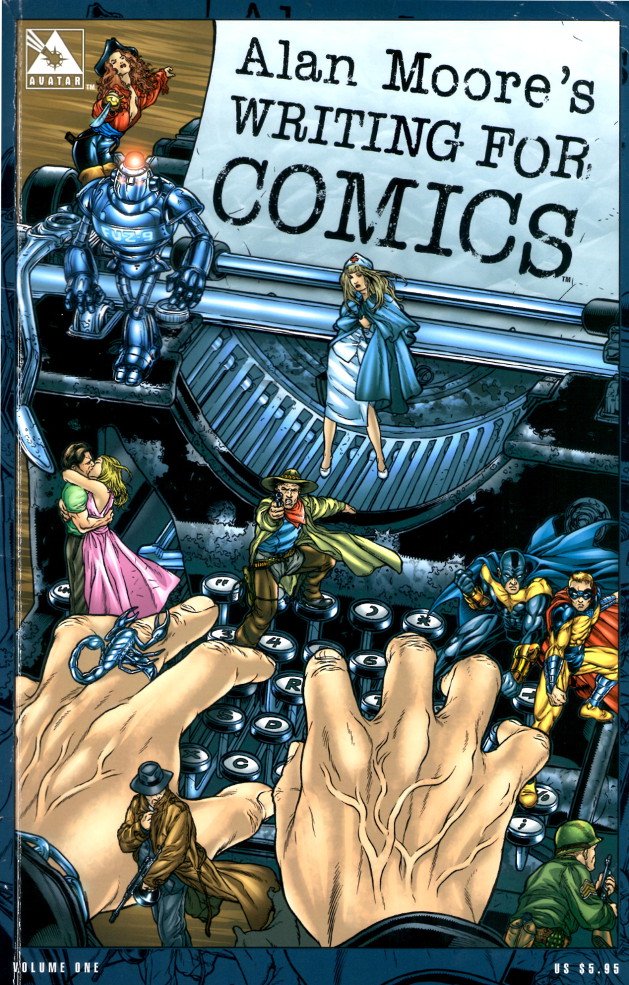

For those who don’t know, Alan Moore is credited with a fresh approach to comics in the mid-eighties with his tenure on Swamp Thing, Watchmen, and various other titles. Shortly after his success, Moore authored the book entitled Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics. The edition that I reviewed was a reprint of the original work with an added Afterword section that was published by Avatar Press in 2006.

As a writer, Alan Moore’s approach to story construction is obviously text-based. That said, it was remarkable how little he dwells on the imagery of the comic in his text. He chooses to confine the majority of his discussion to the thinking process associated with the creating comics. He explicitly avoids saying how he does it

Rather he discusses how to think about the craft of comics writing. The main point here is that a story should be useful in some way – it should be relevant to the reader. He feels that changing printing techniques, adding new characters or new computer graphics won’t make a difference unless the fundamental assumptions of the artform are challenged. And he identifies comics writing as the greater area of focus because it is the very start of the process; the bones on which the flesh of the story is hung.

Story Structure

Moore urges the reader to understand the structure of the work that he is creating; even if the creator is deviating from it, it is important to know that he is. He identifies four types of story structure, most of which he used in his run on the Swamp Thing (note some of the terminology is mine):

- Elliptical structure – the elements of the beginning of the story mirror those at the end

- Middle-Outwards – the story starts in the middle and the background is filled in a way that interleaves the pieces with the current story line

- POV – the same narrative of the story is told by more than one character and only by sifting through the various pieces can the reader determine the facts

- Gimmick – a central piece, like a poem, is used around which the rest of the structure is placed

Once the basic notion of the structure is chosen, Moore then identifies areas of story composition. In this category he includes

- Transitions – movement between one scene and another

- Pacing – the intellectual speed at which that the reader moves through the story

- Rhythm – the balance between active and passive panels*

- Smoothness of flow – overall package of the above*

* Note that these definitions are my own based on my reading of Moore’s intent.

Transitions

Moore labels transitions as one of the trickiest and intriguing elements of the whole story process. The aim of the transition is to move the reader’s attention from one element to another without disturbing his immersion in the story. Moore’s idea is that the reader voluntarily subjects himself to a kind of hypnosis when reading the comic and the last thing that the creator wants to do is to disturb this with an awkward change in focus. Several concepts are proffered as ‘tricks’ to make the transitions better. These include:

- the use of overlapping or coincidental dialog,

- writing in basic units of a page,

- and a repeat of images or concepts (e.g., an idea or a color) between scenes.

Moore does emphasize that the transition need not be smooth if what the creator is aiming for is a jarring change of attention. But again, this is one of these ‘it’s okay to break the rule if you know you are doing it moments’.

Pacing

The idea here is to meter out the duration that it will take a reader to complete their passage through an entire page. Moore doesn’t have a lot to say on this front. He does cite a standard of 35 words per panel, a figure that I had never encountered prior to reading this piece. According to him, an average reader spends 7 to 8 seconds on such a panel. Moore believes that by dwelling on these sorts of concepts, the creator can exercise some control over the duration that the reader spends on each page. To quote Moore

This assertion seems highly questionable based on earlier comments made about the differences between literary works (e.g. novels, short stories, etc.) and film. Moore makes a particular point about the strengths afforded the written work – particularly that the individual reader can set his own pace; moving forward and even backward as he see fit.

What I believe that Moore actually means is that the creator can set the minimum time that the reader must spend on each page by tailoring the amount of written versus rendered information.

Rhythm & Smoothness of Flow

If Moore says precious little about pacing then he says even less about rhythm and smoothness of flow. Specifically, he never mentions them by name again. Getting beyond that point, one can infer possible meanings for him listing them in the first place. The starting point for guessing what he had in mind comes from his insistence that the story is a kind of hypnosis that the reader voluntarily enters. The immediate interpretation is that rhythm is the balance and metering of active versus passive panels. An active panel is one predominantly communicating movement whereas a passive panel communicates location, or thought, or dialog. As far as I know, this terminology is peculiar to me.

This inference is bolstered by Moore’s discussion about the elegance of the fight sequences of Frank Miller, where the active panels are completely devoid of dialog. The action is allowed to happen as in real life without being cluttered by a lot of words.

The smoothness of flow is then judged as the complete package where active and passive panels are knitted together with the pacing and transitions working seamlessly to keep the reader engaged.

Next week, I finish up my summary of the theoretical study of Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics, where I will cover world building and plot and script.