The Business of Comics: Doctor Strange – It Sounded Good

I thought I would shake things a bit this month and focus a bit more on the business decisions made in the comics industry rather than the usual focus of reviewing comic series, looking at overlap of comics with other media, or on the construction of the stories themselves. The case study will be the Doctor Strange: Sorcerer Supreme series that ran from November 1988 to June 1996.

The impetus of this idea is threefold. First, as usual readers might note, I have a fondness for Doctor Strange. While not the flashiest of characters, Doctor Strange has, when handled correctly, present an opportunity for metaphysical exploration that is difficult to find in other venues. Second, this an almost ideal case demonstrating the risk associated with trying to emulate a competitor (in this case Vertigo comics). Third, I had some personal involvement on the far fringes of this story when I engaged in a long and somewhat acrimonious argument with the writer who was at the helm of the book’s demise.

Now an obvious question is why bother talking about an old series now. The simple answer is that the success of the MCU’s Doctor Strange movie did a lot to rehabilitate that character in my mind and it returned my enthusiasm for all things Strange. In turn, that enthusiasm prompted me to give a second look at the series, now with the perspective of time.

Before reviewing the fall of this series, let me set the stage. Marvel was the leader in comics from about 1966 to the start of Doctor Strange: Sorcerer Supreme series. A very helpful chart of the sale figures of both companies has been compiled over at zak-site.com, which clearly shows Marvel sales climbing in the mid-80s while DC’s stayed relatively flat at half the level. Marvel had the upper hand in most things except for adult horror.

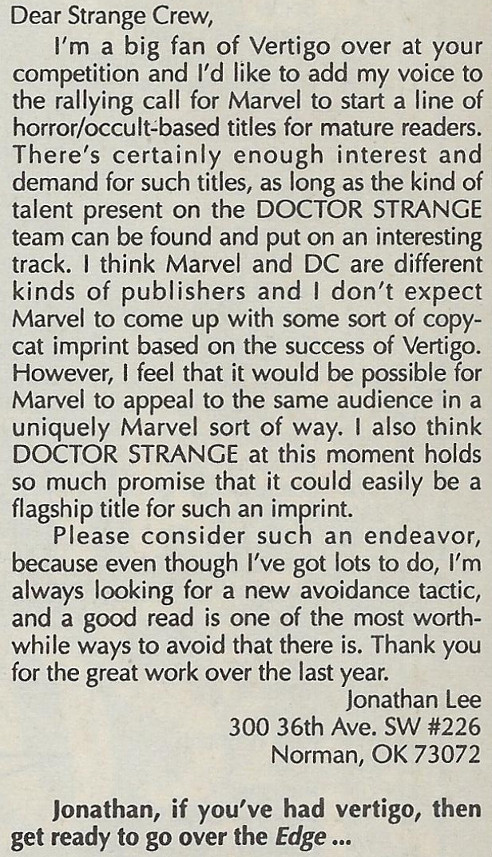

The success of the Swamp Thing under the guidance of Alan Moore in the mid-80s was capped by the popularity of and critical attention paid to the Sandman series, helmed by Neil Gaiman, towards the end of that decade. The Vertigo line that spun off from these two books became one of the one shining spot in DC’s offerings. No doubt, Marvel looked at that and thought there is a market share that they couldn’t or shouldn’t overlook and that whatever Vertigo was doing they could do just as well or better. The following letter and response are from issue #74.

They had a stable of horror-related characters that had served them well in the seventies (Morbius, Hannibal Drake, Blade, etc.) and the relaunch of Ghost Rider in March 1990 proved so successful that a strong competitor line to Vertigo looked in their grasp. Looking for additional characters to join the stable, they decided to reinvent Doctor Strange: Sorcerer Supreme, then a reasonably successful second-tier comic that sold between 70 and 100 thousand issues a month.

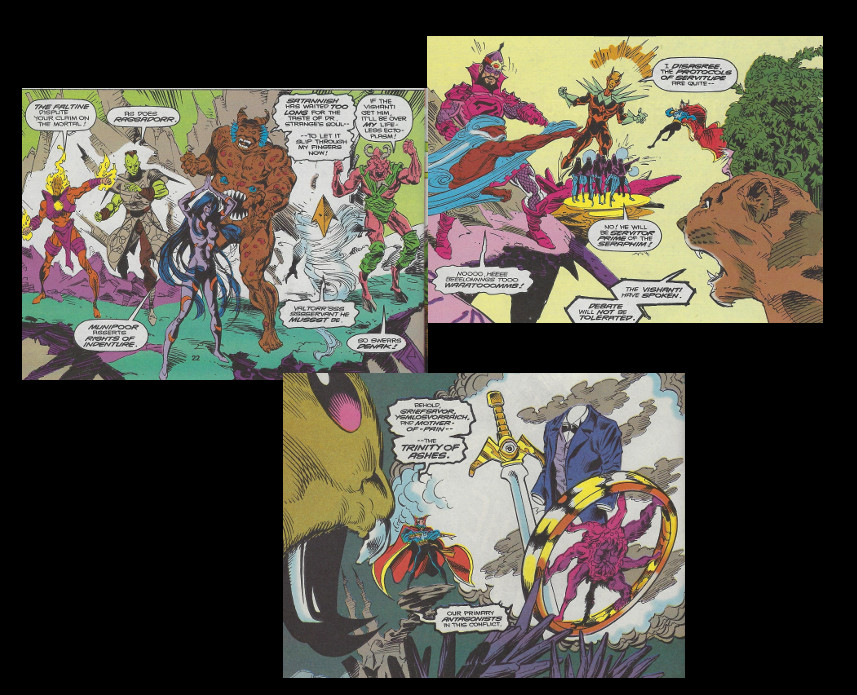

That success was large due to the writing of Roy Thomas, who set the stage for the subsequent transformation with his story device of the War of the Seven Spheres introduced in issue #48. Whether intended to be a plot device for the ongoing story or a strategic move for a planned transformation, the War of the Seven Spheres is a conflict between many (if not all) the extra-dimensional entities – Vishanti, Ikonn, Cytorrak, Watoomb, Seraphim, etc. – upon whom he had often called.

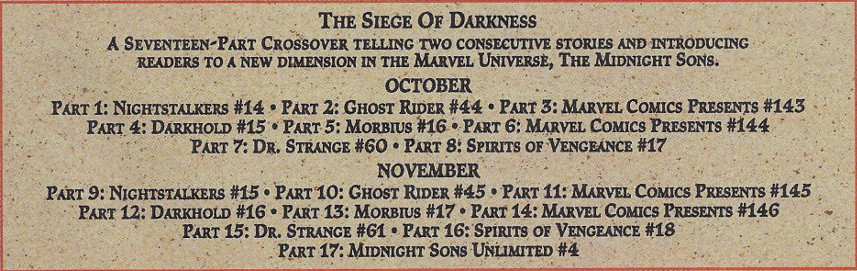

As they fight over who ‘owns’ him, Strange rejects their millennia-long conflict and severs his ties to them, leaving him significantly underpowered and ready for change. That change comes in the form of the of crossover event called The Siege of Darkness.

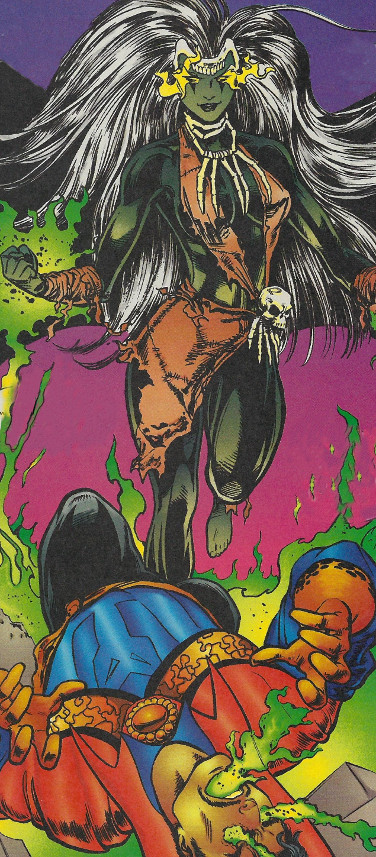

With its roots deeply entwined with the Ghost Rider title, The Siege of Darkness storyline provides a mechanism for rebooting most of the seventies horror characters and pitting them against a host of new villains. The primary one for the purposes of Doctor Strange is an earlier Sorceress Supreme by the name of Salome (a deus ex machina character introduced in Marvel Comics Presents #146)

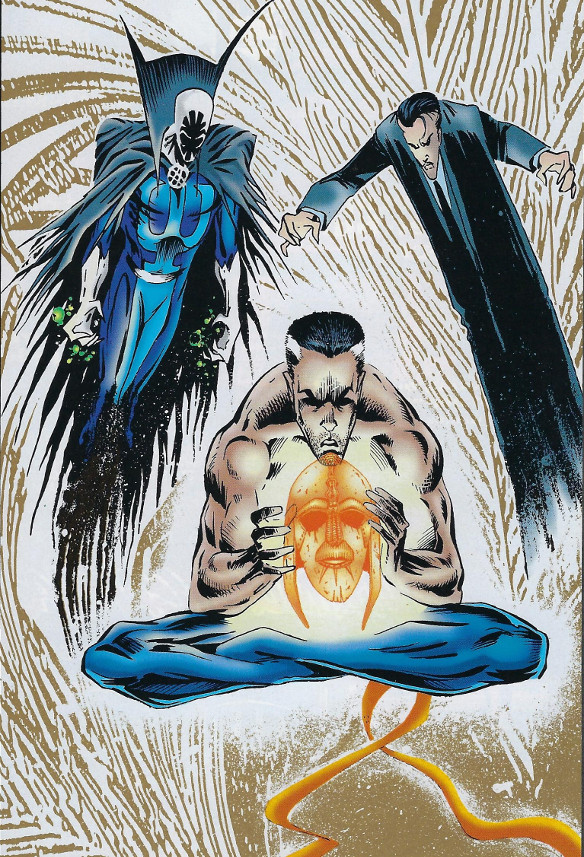

who not only defeats Strange but also ‘infects’ him with her elemental magic. With no extra-dimensional beings to call upon, Strange implements a desperate plan. He first destroys his mansion, then replaces himself in the real world by two magical automatons: a being simply called Strange and Doctor Eric Stevens.

each carrying some of his magical might and a specific facet of his personality (issues #60-61). All that is left is a mere shell of the once great magician

plotting a scheme to defeat Salome with his new Gaian Magic. This sundering persists until issue #75, when the good doctor becomes essentially whole again and much younger in look and manner.

David Quinn, who wrote the series from issue #60, would depart four issues later, his swan song coming in issue #79. By then the damage had been done and no reversal would fix it as series came to an end less than a year later. The following table shows the average and latest circulation numbers by issue from the Statement of Ownership declaration.

| Issue # | 12-Month Average | Latest |

|---|---|---|

| 51 | 110,238 | 132,500 |

| 62 | 105,087 | 67,285 |

| 75 | 52,083 | 40,300 |

| 85 | 35,133 | 31,000 |

Marvel tried to brand the whole family of darker/horror/magic themed comics as Marvel Edge (see letter page figure above) but that branding never seemed to land and hold the way Vertigo did for DC. As the Doctor Strange transformation played out, Marvel editorial staff switched from being generally supportive (mostly positive letters on the letters page in issues #68-74) to frankly critical (no letters pages or strongly negative and critical ones in issues #77-79). This was an unusual move for a company with a history of putting the best face on flagging sales and seems to indicate their vote of no-confidence in Quinn’s method of making the middle-aged doctor appeal to the Vertigo crowd without alienating the pre-existing base.

In a move to restore Doctor Strange to a pre-Quinn state, Marvel hurriedly had him regain support from the extra-dimensional entities by serving in the millennia-long War of the Seven Spheres over a month’s worth of Earth-time along with his middle-aged look and sensibilities; all of this happens between issues, indicating a ‘quick let’s try to fix this’ attitude in the marketing or sales department. J. M. DeMatteis, who became the writer in issue #84, managed to neatly tie up many loose plot threads while also telling a touching story about the final resolution of the relationship between Doctor Strange and Baron Mordo.

And so ended a bold, misplaced experiment by an industry leader trying to emulate a niche-market product by a trendier competitor. There is a certain irony in the demise of Doctor Strange: Sorcerer Supreme. I met David Quinn at the Philadelphia Comic Fest in 1993, just around the time Marvel was building up his forth-coming tenure and the new era it would usher in. Quinn explained his ‘geomancy’ ideas to me and I argued vehemently with him that it wouldn’t work. We stood outside the Marvel booth and argued for over a half an hour before we finally went our separate ways. I was one of those who quickly dropped the book as he transformed the everything in sight. Just recently, I bought the missing issues and read the whole run from his takeover in issue #60 to the end. Taken in totality and read in quick succession, it turns out that the story wasn’t bad and even had interesting and charming parts. But it was a story that refused to honor the past Doctor Strange stories and so alienated the old fans and yet was not edgy enough to attract the Vertigo fans (of which I was one). Sadly, it ended up simply being a dark moment in the business of comics.