Writers and Artists

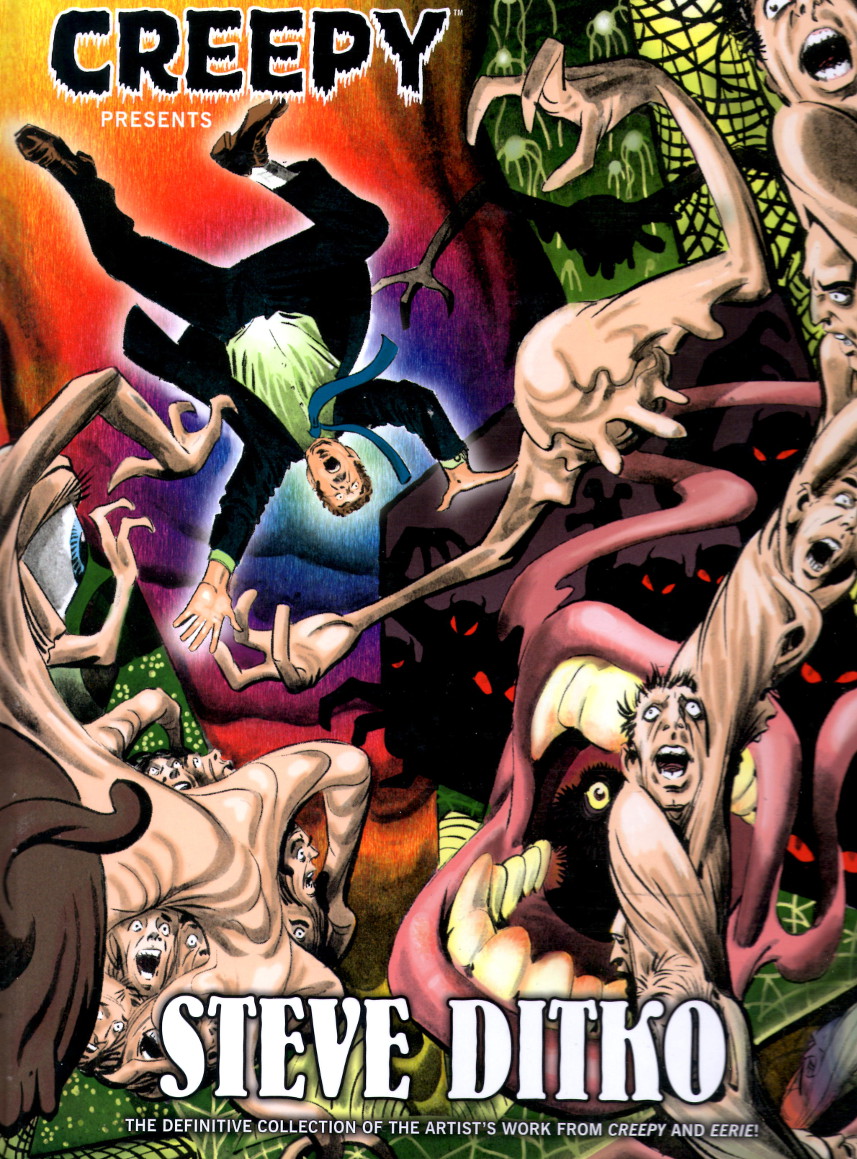

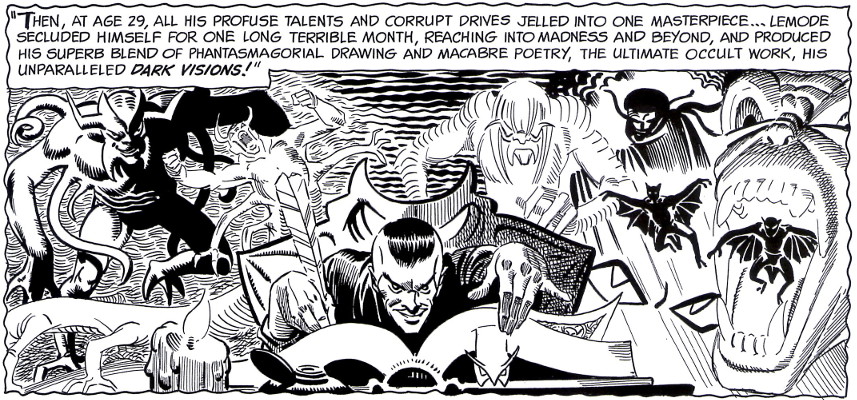

A few short weeks ago, while roaming through the local comic book store, I happened on a reprint volume published by Dark Horse comics entitled Creepy Presents Steve Ditko. As is obvious from my previous columns, I have a general fondness for the old Doctor Strange stories by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. I also have an affection for stories of the macabre – not horror stories per se, but rather weird stories of the bizarre; stories that try to stretch the concepts of reality and reset the boundaries of perception. So, I figured, why not give it a chance.

Once home, I settled into a comfortable spot and looked forward to an hour or two of thought-provoking tales of the twisted and strange. What I got instead was far more food for thought than I bargained for, and none of it from the stories presented in the volume.

In the book’s foreword, Mark Evanier launches into his history of Ditko, essentially in the middle of the tale, by starting with one of the most publicly acrimonious events in comics history: the departure of Ditko from Marvel Comics. As Evanier puts it

Just before Thanksgiving of 1965 – some accounts say February of ’66 – Steve Ditko turned in his last Spider-Man story for Marvel Comics. Anyone interested enough in Ditko to purchase this book knows the grandeur of that work and the major jolt in comic book history that occurred when it ended.

His resignation was not wholly unexpected. He and editor-scripter Stan Lee had not been getting along for quite a while, disagreeing as they did about the direction of the series, the underlying philosophy of it and its world, and the division of their labor.

Whether Evanier meant his words to be a distraction or not, I found myself quite unable to concentrate on the stories themselves. Instead, I kept returning to the reoccurring debate as to who is more important: the writer or the artist.

The tension between artist and writer is a reoccurring theme in the comics industry. I was present at the Great Debate between Peter David and Todd McFarlane at the ’93 Comic Con in Philadelphia. For those who don’t know, David (writer) and McFarlane (artist) had a fine run on The Incredible Hulk before they had some sort of falling out. The debate, which was an aftershock of that split, was handily won by David. And considering that the book barely lost a step with the departure of McFarlane, one might be inclined to say, at least in this case, the artist was not as important as the writer. This is a well-supported conclusion given the paucity of storytelling demonstrated by McFarlane in his book Spawn.

On the other hand, John Byrne demonstrated that an artist can be quite a great storyteller, in fact better than the writer he was originally paired with, when he moved off of The X-Men and out from the shadow of Chris Claremont.

The situation is far more complex and nuanced in the case of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Together, this pair created two of the most enduring comics characters in Spider-Man and Doctor Strange.

Exactly how should the credit be apportioned between the two of them for the creation of Spider-Man has been the source of much debate. Was Lee the driving force behind the idea while Ditko merely set the visuals? Or was Ditko’s costume design and moody panels the key with Lee’s writing taking a back seat?

I think the answer lies not in one pole or the other but in the tension that resulted from their opposition. In his article on Ditko (The Creator of Doctor Strange Will Not See You Now), Abraham Riesman says

Even as they were crafting these early adventures of Spider-Man and Peter Parker, there was friction between Lee and Ditko. At first, it was productive: Lee loved poppy, witty, ingratiating verbiage, but the characters Ditko put into the stories often looked unnerving and anguished; Lee liked high-flying action, Ditko wanted pathos.

…

The resulting character was unlike any other in the superhero corpus: an awkward, despairing, and oft seething teenager who struggled through life both in and out of costume, but managed to banter his way through the darkness and always triumphed in the end. He was a kid who saw his powers as a burden and only assumed a heroic mantle after tragedy forced him to reevaluate his life choices, but who leapt and swung along the rooftops with acrobatic aplomb. It’s hard to imagine either Lee or Ditko coming up with such a contradictory and revolutionary character on their own.

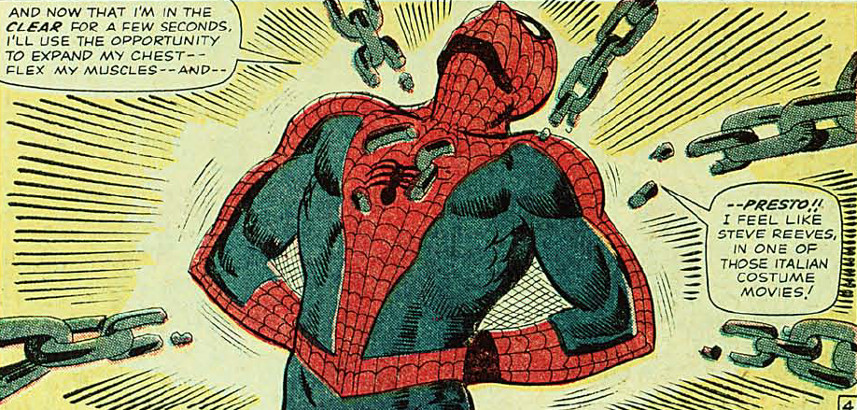

And contradictory it certainly was. Consider this panel from The Amazing Spider-Man #27. Ditko’s art is wonderfully expressive while also being minimalist. Just Spider-Man and the chains. Is this panel really helped by the campy dialog that informs the reader that Peter has flexing chest muscles that make him feel like a bodybuilder in a b-movie?

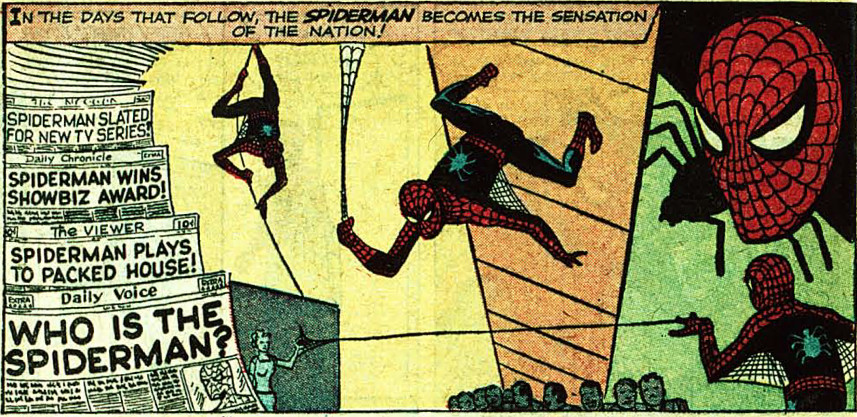

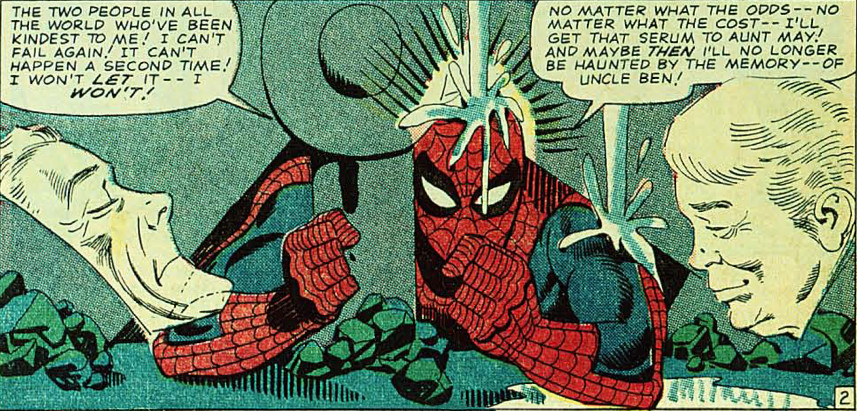

On the other hand are the following panels extracted from Amazing Fantasy #15.

It’s hard to say that Ditko’s art is inspiring but the dialog and captions are top notch, including that well-worn quotation about great power and great responsibility.

Of course, there is a lot of speculation as to what made Spider-Man so successful. Certainly, his costume is visually appealing and the overwhelming consensus is that Ditko is responsible for the look and feel. But the main aspect that makes it all so compelling is the tragic back-story, which seems to be due to Lee. It is always harder to clearly apportion credit for plot points.

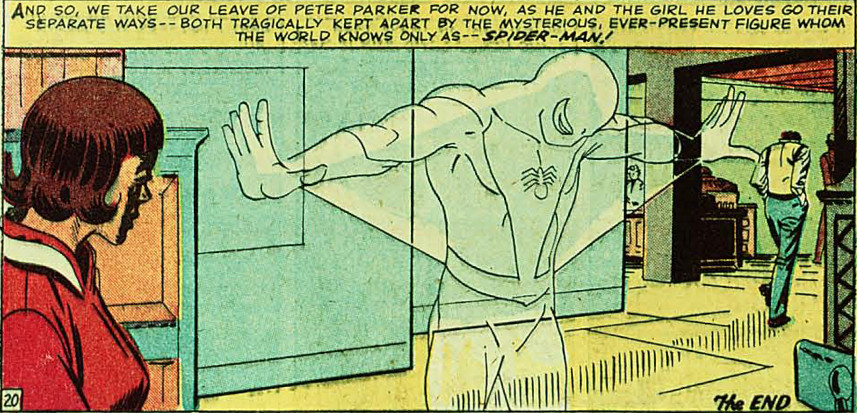

During their collaboration, Lee and Ditko produced memorable moments that neither achieved afterwards, including the iconic ‘Spider-Man coming between’ Betty Brant’s and Peter Parker’s burgeoning romance (The Amazing Spider-Man #30)

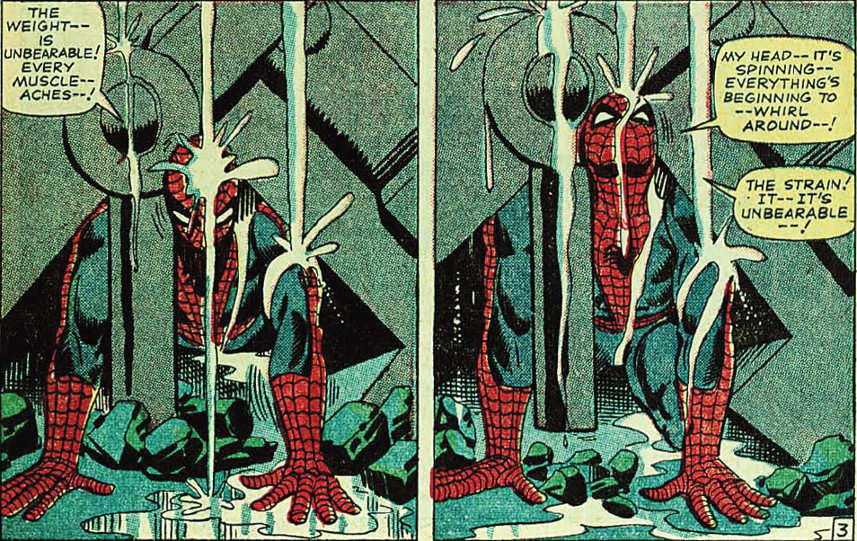

or the famous sequence where Peter is trapped by Doctor Octopus under tons of wreckage (The Amazing Spider-Man 33)

where he refuses to give up until he is free.

Lee’s words and Ditko’s art perfectly complement each other and the reader is left with a story that is a profound blend of courage, sadness, hope and despair.

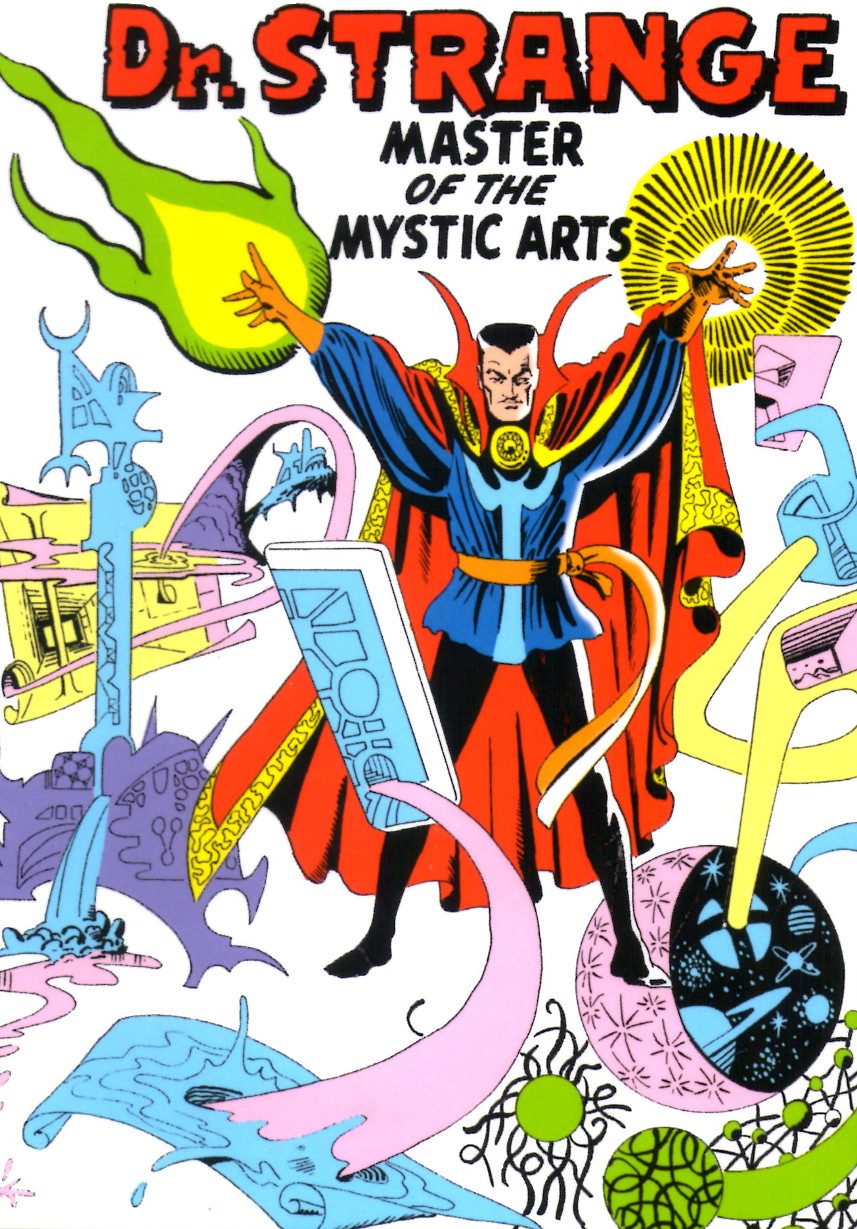

The Amazing Spider-Man continued to do well after their split and one might argue that the later arcs involving the Kingpin and the death of Gwen Stacy surpassed the work by Lee and Ditko. But in the case of Doctor Strange, their pairing produced a set of stories involving the famous sorcerer that have never been equaled since.

Ditko’s surrealistic images created a new standard in comic book visuals for magical storylines. Lee, drawing on his background writing ‘weird’ stories, created imagination-stirring concepts that blended horror, the macabre, and mysticism without feeling trippy or forced. The pinnacle of their collaboration can be summarized with one image: the encounter between Strange and Infinity, the living embodiment of the universe.

This encounter would not be the awe-inspiring event it was without the Ditko’s visuals to set the mood and without Lee’s storytelling, which built up suspense over the previous 7 stories/84 pages in which Strange raced against time to find a way to defeat the alliance between Baron Mordo and Dormammu.

Neither creator was ever as successful in capturing comic book magic again. Clearly, despite whatever emotional animosity lay between them, their whole was greater than the sum of their parts. Without Ditko’s imagery to inspire, Lee’s subsequent stories began to age, to became tired, repetitive and dated. Without Lee’s plots and words, Ditko’s visuals seemed disassociated and unmotivated.

They had captured lightning in a bottle when they teamed up; too bad it couldn’t last.