Watching the Watchmen – Part 1

I’ve had something of a love-hate relationship with the Watchmen comic series since it first premiered in September 1986.

This admission may seem something of a surprise given that the Wikipedia article on the Watchmen notes that “several critics and reviewers [consider it] to be one of the most significant works of 20th-century literature”, that “Watchmen was recognized in Time’s List of the 100 Best Novels as one of the best English language novels published since 1923”, and that “[t]he BBC described it as ‘The moment comic books grew up.’”.

I’ve heard things like this since Watchmen hit the stands in 1986 and I scraped enough money to buy it in its original serialized form (a huge task given that I was in college at the time with very little money). But I have never been able to fully embrace it nor to clearly explain why. That’s 30 years of pondering what is it about this particular comic series that attracts me and what pushes me away. It’s 30 years of wrestling with how to clearly articulate the reasons why. Finally, I think that after all that time I can, at least, put down the basic structure behind my ambivalence towards Watchmen.

In a nutshell, I think the physical composition and narrative structure are among the best I’ve ever seen while the underlying message and philosophy are empty and nihilistic and vapid.

I’m going to spend this column and the next expanding on particular points that support this assertion starting with the parts of Watchmen that I like – its physical composition and the narrative structure. In the next column, I’ll discuss the underlying themes and messages that produce a philosophy that is both nihilistic and intellectually vapid.

But before launching into the review, a quick synopsis of the plot is in order. For those unfamiliar, Watchmen is set in an alternative timeline where some ‘normal people’, inspired by the pulp novels of the 1930s and 1940s, have become masked adventurers for a whole host of reasons, which, according the psychoanalysis featured in the story, include a desire to address societal woes and do good, the need to get their kicks (physically or sexually), or because they are seeking their fame and fortune. Being a bit of a fad, these normal folk in extraordinary costumes see their popularity rise and fall just as any fad does. Things change about a decade later when the physicist Jon Osterman, through fate or blind randomness, becomes the superman of his world. Dubbed Doctor Manhattan, Osterman is able to manipulate matter at the atomic/sub-atomic level, teleport, bi-locate, and ‘see’ the past, future, and present all at once. His presence re-energizes the superhero movement, causing a new generation to don masks and tights and fight for justice. However, this new influx is ultimately viewed as a destabilizing influence on society and ‘masks’ are outlawed by the Federal government in 1977. The Watchmen is set in 1985, when the only legally operating superheroes are Doctor Manhattan and the brutal, cynical holdover from the earlier days called the Comedian.

The Watchmen starts proper with the death of the Comedian at hands unknown. The story features the ramifications that result as the other masks – Rorschach, Nite Owl, and Silk Spectre – investigate the Comedian’s murder. As the various threads are put together they slowly realize that the Comedian’s death was engineered to hide the scheme of Adrian Veidt, a.k.a. Ozymandias, a former compatriot, who has taken on the responsibility to save the world from itself. Ozymandias‘s plan is simple; fool the people of Earth into thinking that there is a cosmic threat waiting to invade and they will unite against a common enemy. Ozymandias/Veidt is willing to kill millions in New York with a simulated invasion by a monstrous alien in order to drive the threat of invasion home. At series end he is both condemning and congratulating himself for having pulled off what he, no doubt, would term a Platonic noble lie that brings peace to the whole world.

Written predominantly as a psychological exploration, the action in Watchmen is fairly limited but the moral and existential horrors drip from every page. Part social commentary, part critique of comics, part moral play, the 12-issue series was different from much (but not all as many critics believe) that was on the market at the time (the Squadron Supreme 12-issue series from 1985 has nearly identical themes – albeit dealt with differently – and premiered about a year and a half earlier, but that is a post for another day).

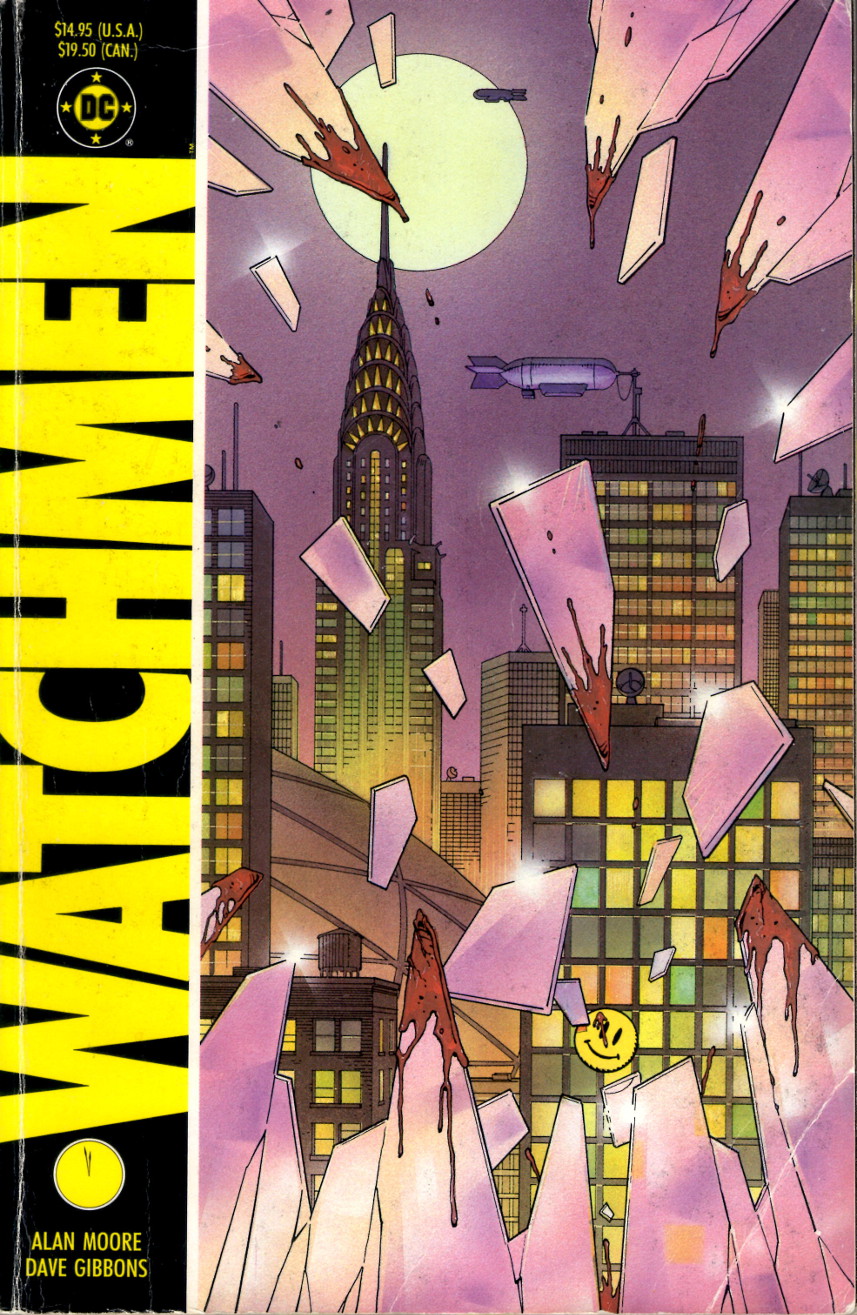

To emphasize that the Watchmen was something other than the run-of-the-mill comic, writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, tried to design a look-and-feel quite different from anything that was currently in vogue. They did this in a number of interesting and successful ways:

- Page layout

- Panel detail

- Background material

- Repeated visual elements

- Repeated narrative elements

Page Layout

Throughout almost every page of the visual material, Dave Gibbons uses a 3×3 grid with the smallest panels measuring about 2 inches wide by about 3 inches high. The main variation in this layout is to combine these atomic panels into composites that span more than one column and/or row. Despite Moore’s protests to the contrary, this gives the entire series a movie storyboard feel, as seen in this ‘silent sequence’ showing how Rorschach gets into the Comedian’s apartment at the start of his investigation.

This is why so little of the core plot needed to be cut from the comic for the successful adaptation of the Watchmen into the movie (and in fact some new material was added). Gibbons does depart from the strict 3×3 grid in a few places (pages 6, 12, 16-17 & 27, and 28 of issues #1, #2, #7, and #11, respectively) but these are places where time is meant to move more slowly than in the normal pacing of the book.

Perhaps the most interesting experiment and one that I missed until it was pointed out to me, is that issue #5, entitled Fearful Symmetry, is completely symmetric front to back (a comic book palindrome). For example, the first three pages are in a 3×3 grid with Rorschach at the apartment of an old supervillain named Moloch. Likewise, the last 3 pages (26-28) are a 3×3 grid showing Rorschach at Moloch’s apartment. Page 9 is a mirror image of page 20, both having 3 panels per row (one spanning two columns in each) and both dealing with the comic-within-a-comic story about the Black Freighter. The central opposing pages (14 and 15) have one continuous fight sequence rendered in ‘fearful symmetry’.

Panel Detail

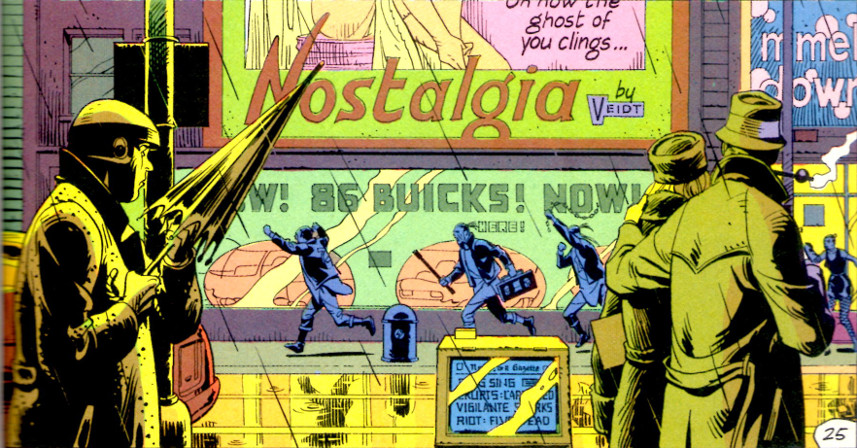

Besides the overall panel placement within the page, Dave Gibbons put a great deal of effort into the contents of each panel as well. As can be seen at a glance, the detail in each panel is top notch, but attention to detail for art’s sake alone is not nearly as impactful as is detail that advances the story for the careful reader.

Below is a panel from one of the many street scenes in New York. The first things that grab one’s attention in the background are the advertisements for the ’86 Buicks and the Nostalgia perfume – both serve a purpose. While the Buick ad helps to remind the reader (especially the new ones) when this piece is set, it is the Nostalgia ad that actually provides important clues linking Veidt with the plot to hoax the world. The newspaper in the foreground gives the reason for Veidt’s intervention – the nuclear war that is about to break out between the USA and the USSR.

Scores of panels all throughout the series provide similar clues linking the World War III events with Veidt’s scheme to bring the world kicking and screaming back from the brink.

Background material

Since psychology plays a crucial part in the Watchmen storyline, Moore provides extra, non-comic material, usually spanning the last 4 pages. These materials include: excerpts from books and articles written by the main characters, which enable us to get inside their heads; dossiers and internal memos from the various institutions associated with other main characters; and news and magazine articles that reveal the public mood and discourse to the reader. One cannot fully appreciate what is happening in the gutters and why it is happening without taking the effort to ‘research’ the Watchmen world.

Repeated visual elements

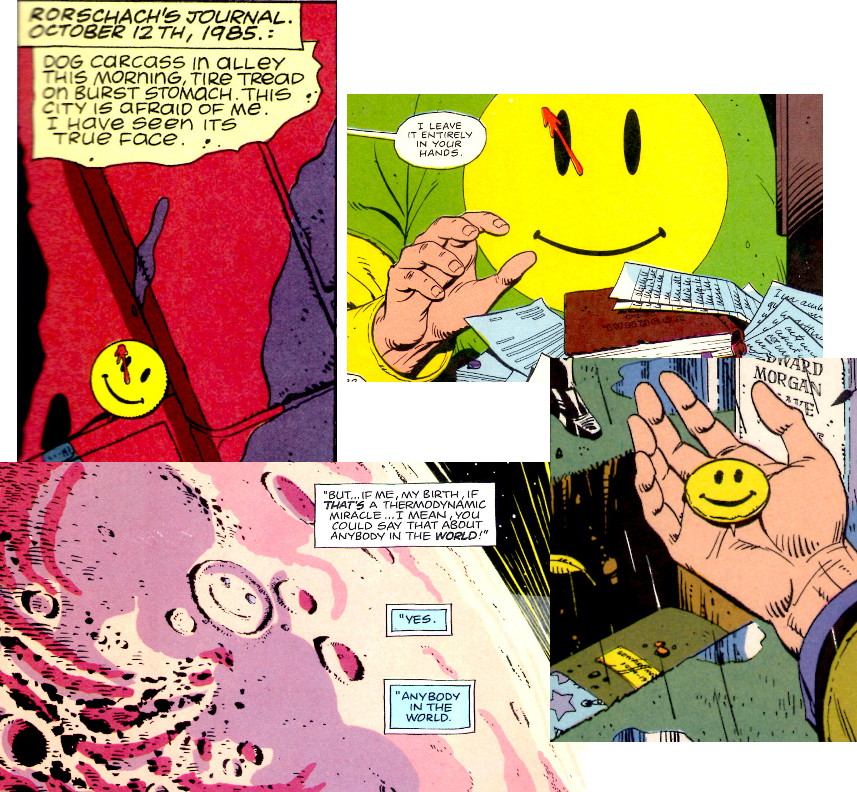

Similar to the panel detail discussed above, Moore and Gibbons link various events together with repeated visual elements. The most well-known one is the smiley face motif that links the Comedian with cataclysmic events that started the whole chain of events that ends with the mock alien invasion.

A less obvious visual motif is the reoccurring imagery of the Nostalgia perfume. Not only does it link Veidt to the desire to change, it provides a vital link to Ozymandias in that the perfume bottle, when turned on its side, looks like a letter Z contained within the letter O. This visual linkage appears at least 7 times in issue #9 when Laurie (Silk Spectre) and Jon (Doctor Manhattan) debate whether life has any meaning while they travel across the face of Mars.

The most disturbing repeated element concerns the behavior of the Comedian, aka Eddie Blake, around women. It seems that Blake believes that women are there for his gratification and he easily brutalizes them when they don’t “behave.” It is interesting to note that in the two cases shown in the book, when Blake begins to ill-use a woman, her response is to attack by scratching/slicing the right side of his face.

These scars remain with him until he dies – an outward symbol of his inward sins perhaps.

Repeated narrative elements

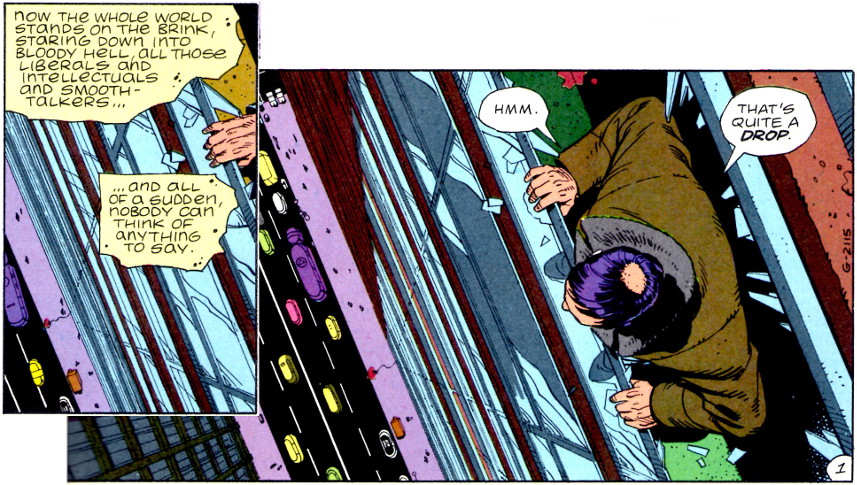

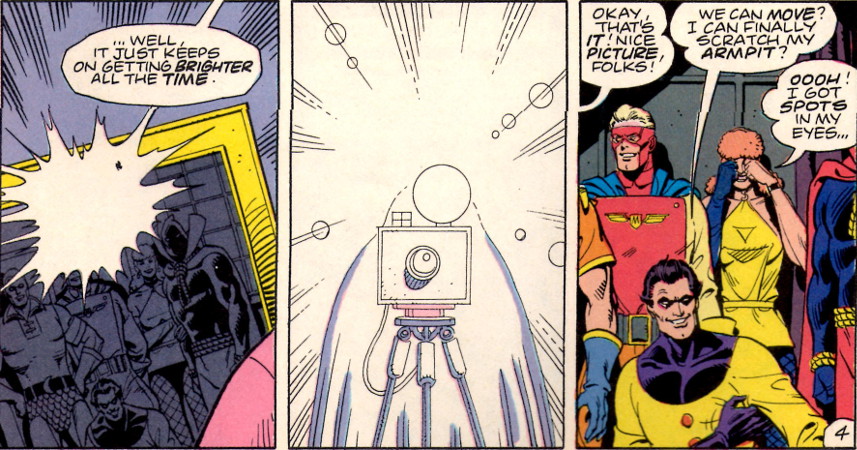

The final method used by Moore and Gibbons is the linkage between disparate sub-storylines by using the kinds of transitions that Moore discusses in his book on writing comics (see Story Construction – Part 7: Just One Bit Moore).

The first panel below shows how, with some dark humor, Moore is able to transition from Rorschach’s monologue that begins issue #1 to the detectives investigating the death of the Comedian.

This next example is a classic movie transition that signals a flashback to earlier times and happier events (ah, Nostalgia).

All told, these five elements make the form of the Watchmen a pleasure to see, to read, and to ponder. They go a long way in explaining the enduring success of the series and they certainly are the best part.

Next month, I’ll analyze the content of the Watchmen messages and not just the beautiful package in which they are wrapped.