Sandman Overture

Back in 1989 Neil Gaiman breathed new life into some old characters that had been gathering dust on the DC shelves. All that was required was a reimagining of the character Destiny, a nudging of the Sandman character into universal, cosmic status as Dream, and the rounding out the 5 other ‘Ds’ (Delirium/Delight, Despair, Death, Destruction, and Desire) to form the 7 Endless. Each of the Endless were portrayed as anthropomorphizations – human-looking embodiments of the elemental forces of the same name.

Gaiman’s tale starts with the imprisonment of a punk-rock looking Dream by an Allister Crowley knockoff and his coven of demon worshipers in 1916. The subsequent humiliation/education that Dream endures and the changes that it engenders in him forms the central tragedy of the bulk of the series. A tragedy presented on human terms.

Initially, the stories had an intimate feel; a feel reminiscent of the classic British Cozy made so popular in mystery stories of the first half of the twentieth century. Action was confined to small venues with real human issues. The horror of John Constantine’s former lover who abused Dream’s pouch of sand, the twisted events that Doctor Dee brings to life in that lonely dinner, and the convocation of serial killers headlined by one of Dream’s own nightmares were excellent examples of what could be done within a small scope.

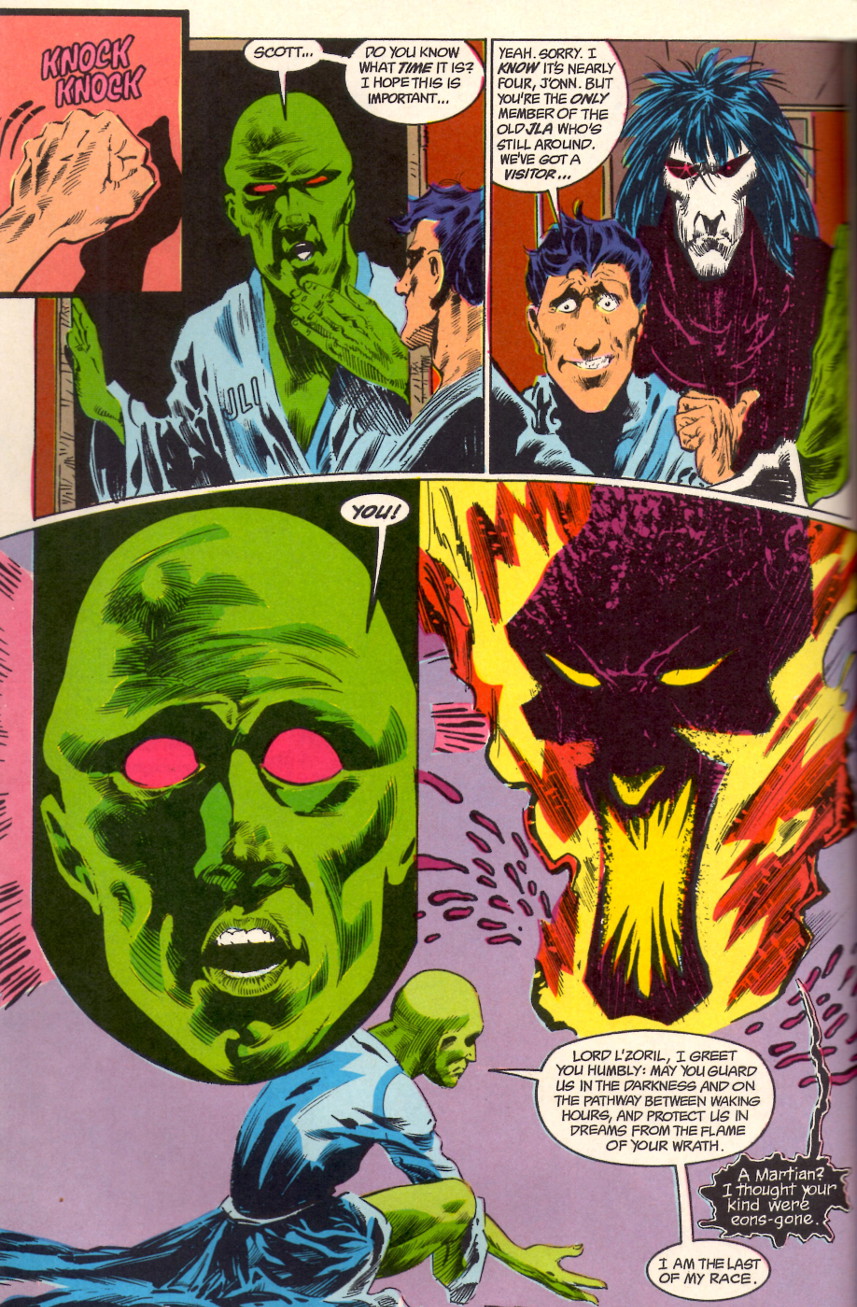

Unfortunately Gaiman couldn’t stay small and he tried to grow Dream to something more cosmic and universal. The beginnings of this were evident when the Sandman paid a visit to J’onn J’onzz the Martian Manhunter in Sandman #5.

Dream was perceived as the Martian dream god Lord L’Zoril by J’onn. On one hand that makes perfect sense as Dream is a universal concept and how should an universal concept be apprehended by a Martian except in Martian terms. But on the other hand it is clearly untenable. How can Dream be in on specific place let alone be captured and imprisoned for over 70 years. After all, Dream is an Endless – he is an incarnation of a universal concept. If he were an agent or an avatar it might make sense but not as an incarnation.

As the series progressed, Gaiman swerved from the intimate to the large but never to the truly universal. All of his concepts were firmly rooted in the kind of classics education one might get at Oxford or Cambridge. Even Dream’s undoing comes at the hands of the Furies; embodiments of the spirits of familial vengeance from ancient Greece.

So it was with ever diminishing interest that the series wound on until its end in 1996 with the death of Dream and the subsequent installment of a new Dream.

Little of note occurred over the better part of two decades until Gaiman decided to revisit the Sandman with his prelude entitled Sandman: Overture. In this limited series, he seemed to want to really ‘fix’ all that ailed the original run; addressing both the universality of Dream and how he came to be captured. In order to do this, he puts Dream into a cosmic quandary, where the fate of the entire universe hangs in the balance. And while the artwork is beautiful and the craftsmanship inspired, what actually resulted is a confused story that causes more confusion than it addresses.

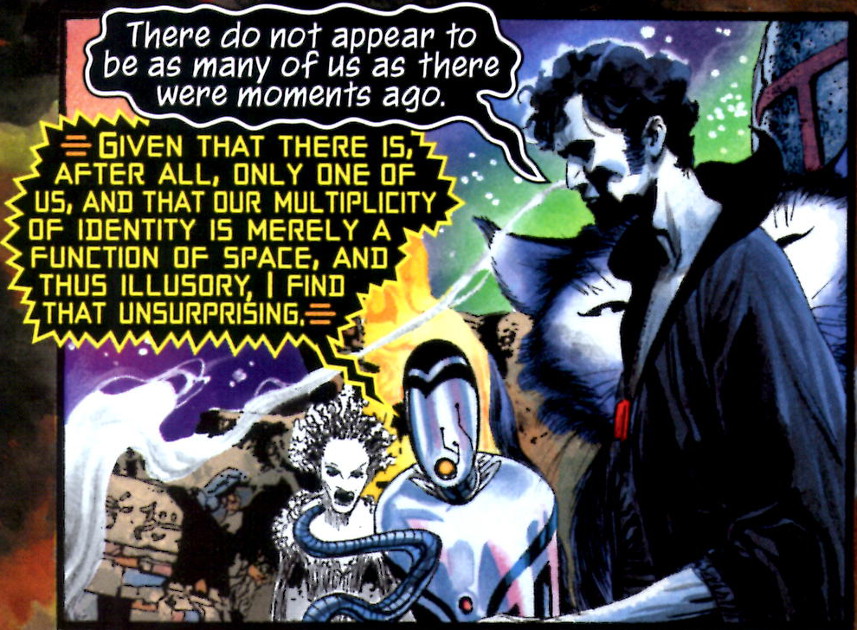

This time it all starts with the death of Dream in 1915 – well at least an aspect of Dream and that is one of the problems. This death triggers a gather of Dreams, each representing a sliver of the totality of Dream, one for each type of being in existence.

Each aspect trying desperately to understand what has caused this train of events, to understand who killed them.

Fortunately for the exposition, an particular aspect of Dream with a strong elder-gods motif, acts as the hermetic monks of old stories did, and steps in to fill in the gaps.

This aspect explains, in pure vagueness, that the universe is coming to an end. However, before he can speak with more clarity he vanishes. This is not an unusual occurrence, and as time moves on, the Dream population mysteriously begins to thin as each aspect disappears from the perspective of the others

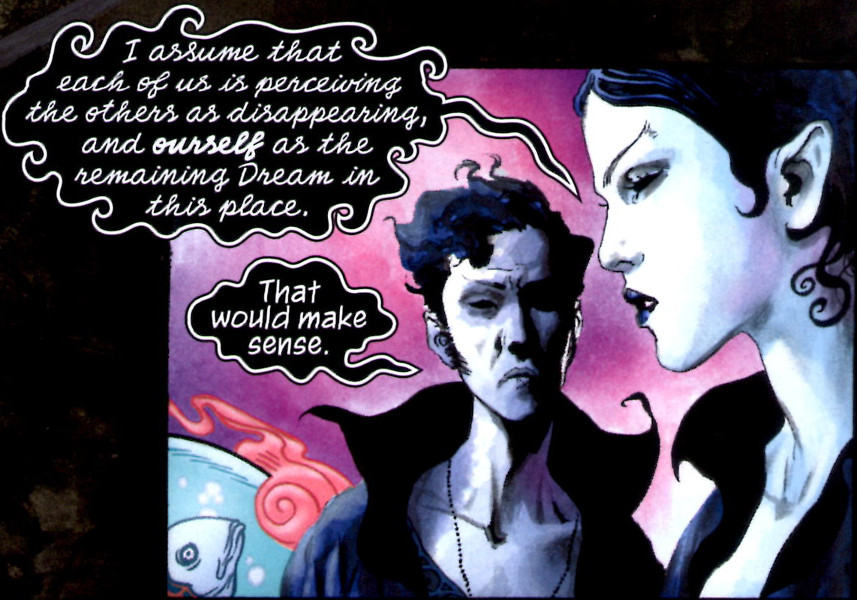

After consulting with himself/herself/itself, Dream explains that the disappearances are only a matter of a different point-of-view.

Our Dream, being proud and haughty (aren’t they all?) takes it upon himself to seek a higher authority

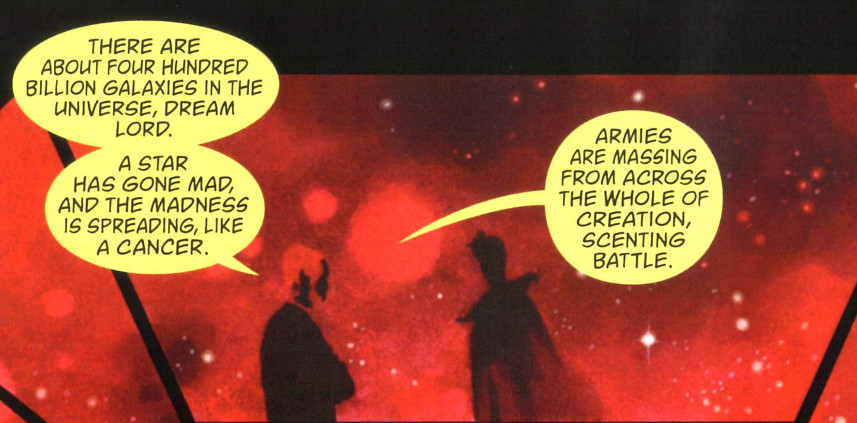

and off he goes to consult with a level of authority above the Endless. Here finally all is revealed. This uber-entity informs Dream that the cause of the death of one of his aspects is due to a cancer eating away at the heart of the universe. A star – stars are sentient in this telling – has become mad and is driving existence to Armageddon.

And it turns out that one need look no further than Dream to find the cause of this disaster. By failing to totally obliterate a ‘vortex’ from existence, Dream’s inaction has led to this sorry state of affairs.

And so begins a quest in which Dream looks for a way to correct his mistake, fulfill his duty, and save the universe. Along the way, he encounters his father, Time, and his mother, Night; he’s cast into a black hole; and rearranges the entire spacetime continuum as he literally erases his error from history. The action leaves him so drained that capture shortly after is all but inevitable.

I suppose that Gaiman thinks he’s done something remarkable here by ‘tidying up’ all the loose ends but that’s not how I see it. Splitting Dream into multiple aspects waters down the original run, making our emotional investment in the original insignificant. Philosophically, the whole concept of a multitude of aspects of universal concept is also dodgy. If they are the same but different, why should any care if one is annihilated, and which one was captured, and so what if he was? Why couldn’t a new aspect take over in his place? And if he was the aspect peculiar to the Earth, then why did a Martian see him as a Martian dream god? Too many questions with too few answers.

Gaiman is also open to criticism on his physical cosmology. The work is not strictly a work of fantasy since he uses the trappings of science to make his story have a veneer of credibility. He even went so far as to have pictures of bubble chamber tracks superimposed on Hubble-like pictures of stellar nebulae on the insides of the front and back covers.

How can it be 1915 everywhere in the universe? What about relativity and the finite speed of light. I guess getting the science right doesn’t matter as long as it sells.

Many months ago I talked about the three most foolproof ways to screw up a comic. Here Gaiman indulges in all three. He’s got illogical magic, a multiplicity of doppelgangers, and time travel with a universal reboot.

I’m not saying that the whole thing is a waste. Certainly as a flight of fancy it’s worth taking a look and the art is gorgeous.

But as a story, it comes up quite short of the mark. Gaiman’s Sandman was always much better when it was confined to the small and when it embraced its classical, Western roots rather than trying to be universal.