Story Construction 11– Peter David on Plot and Script

This week’s column completes a two-part study of the work Writing for Comics & Graphic Novels by Peter David.

David defines the plot as having two aspects. The first is the development of the hero as an individual. The second is the events that serve as a vehicle for that development. This later piece is called the plot.

According to David, the plot doesn’t necessarily require choice from the character. For this he cites the movie The Terminator which forces Sarah Connor to grow up. I find this somewhat hard to swallow, as Connor always had the choice to just lay down and die rather than stiffen and fight back. I interpret that he is trying to say that whether the character is predestined to be subjected to a set of events or that the character’s choices shape those events is not important. What is central is that the character evolves inside as the events evolve outside and that it is this internal evolution that readers find compelling.

On plot pacing, David suggests that all scenes be trimmed down to the essential information. To this end, he advises, like O’Neal, to start and end on the action, whether that action is physical (i.e. a slug fest) or mental (i.e. a test of wills) or emotional (i.e. a fight between husband and wife).

Like Moore, David also advocates for connectors (as he puts it) between scenes have a thematic overlap, like using the same words, albeit in different contexts, to end one scene and begin the subsequent one. Another feature that David advocates in common with Moore, is to end a scene at the end of a page where possible.

At its most basic level, the story structure that David recommends is one that is a combination of ups and downs (roller coaster) superimposed on an overall rising action to the climax with a small release at the end for the denouement.

To this end, he offers the three-act structure is a good model. Unfortunately, he defines the essential pieces of the three-act structure using the movie the Karate Kid, which makes it a bit difficult to understand the theory as a whole (unless you know the movie exceedingly well or are willing to watch and rewatch as you read his books). As near as I can render it, David defines these essential pieces as:

- First act used to introduce the setting and cast

- First-act turning point where the essential problem is introduced

- Second act used to define the stakes of the problem and intensify the tension

- Second-act turning point where some complication arise or where the hero gets some insight into what lays before him

- Third act where the problem resolution crystalizes into a simple choice

- Climax where the here chooses and the problem is resolved one way or another

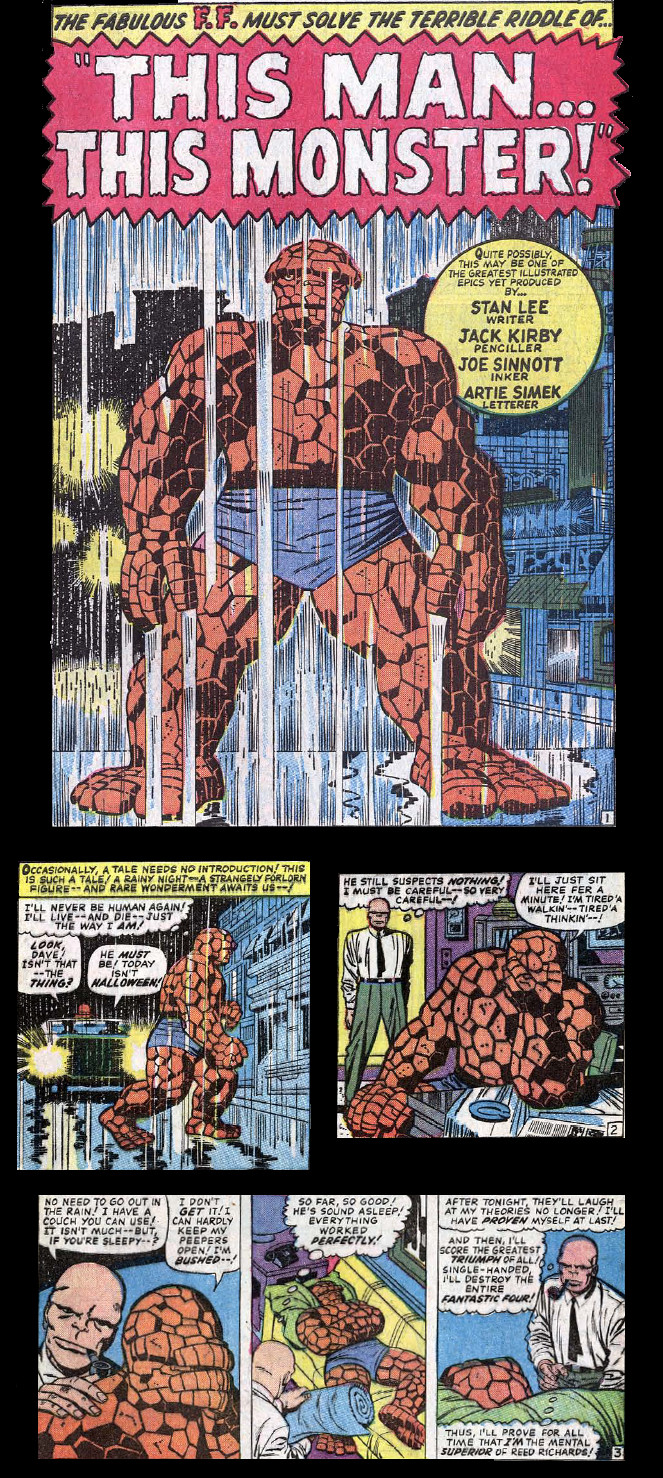

As a textbook example of the three-act visual storytelling, David proffers issue #51 of the Fantastic Four. Since it was a standalone issue, it was easy enough to dissect, and David includes many of the pages from that issue to illustrate the main points. I’ll try to summarize them verbally and visually, although it should be noted that I draw the line between the second act turning point and the third act differently than David.

Act 1 establishes the situation. We start with the Thing standing in the rain and feeling sorry for himself. He eventually meets a mysterious man who invites him in out of the rain and who, through some heavily drugged coffee manages to get the Thing to fall asleep.

As we near the end of Act 1, the turning point is reached where we now see that the mysterious man (called the Changling) is going to steal the Thing’s powers in order to exact revenge on the Reed Richards

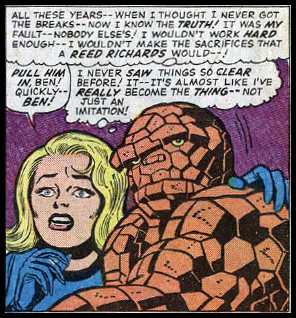

Act 2 deals with the consequences of this switch. Being able to pass himself off as the Thing, the Changling infiltrates the Fantastic Four and suspense builds as his plans for revenge go unnoticed by everyone but a now all-to-human Ben Grimm.

Act 2’s turning point comes, when the Changling finds himself able to affect his revenge simply by inaction. Reed Richards, having invaded sub-space, approaches a region where all the negative matter, including him, is being annihilated with positive matter. Reed will be destroyed if the Changling doesn’t reel him back in with the tether, one end of which is attached to Reed’s suit and the other is in the Changling’s hands.

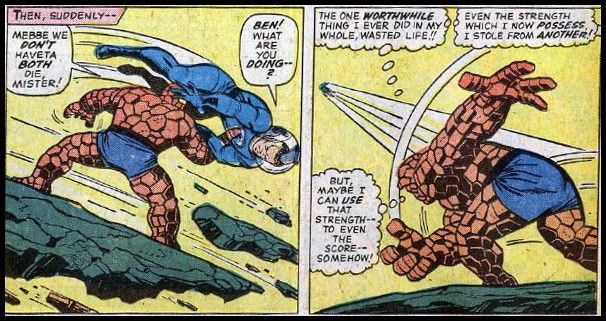

Act 3 plays out when Reed’s tether breaks and the Changling and a horrified Sue watch as Reed plummets towards certain doom (that is actually an oxymoron in comics but never mind that now). The Changling has s single choice to make. Do nothing and reap his reward as Reed dies or make an effort to save the man he has hated for years. Here the thought balloons scripted by Stan Lee show the Changling’s internal conflict.

The Climax comes when the Changling decides to save Reed’s life at the expense of his own.

The clean-up and denouement of the story re-establishes the status quo until the next issue where it is disrupted all over again.

As a side note, it is interesting that David mocks the standard plot construction put forward by Jim Shooter (although he doesn’t cite him by name) that the poem Little Miss Muffet was a perfect form of storytelling as it has all the needed elements:

- The set-up or the establishment of the status quo (“Little Miss Muffet sat on her tuffet, eating her curds and whey)

- The action motion (“Along came a spider and sat down beside her”)

- The reaction and resolution (“And frightened Miss Muffet away”)

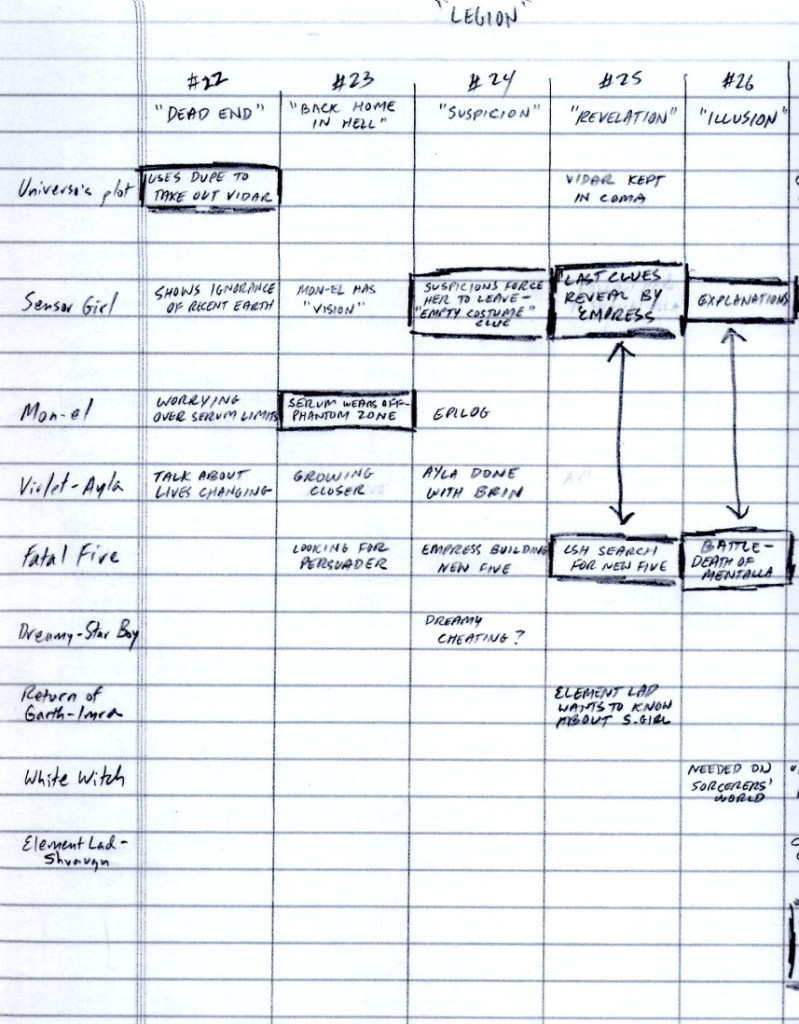

David also discusses at some length the idea of having intersecting story lines that rise and fall independently when they are not overlapping each other. I found this discussion a bit hard to understand in practical terms but I suppose that it comes with practice.

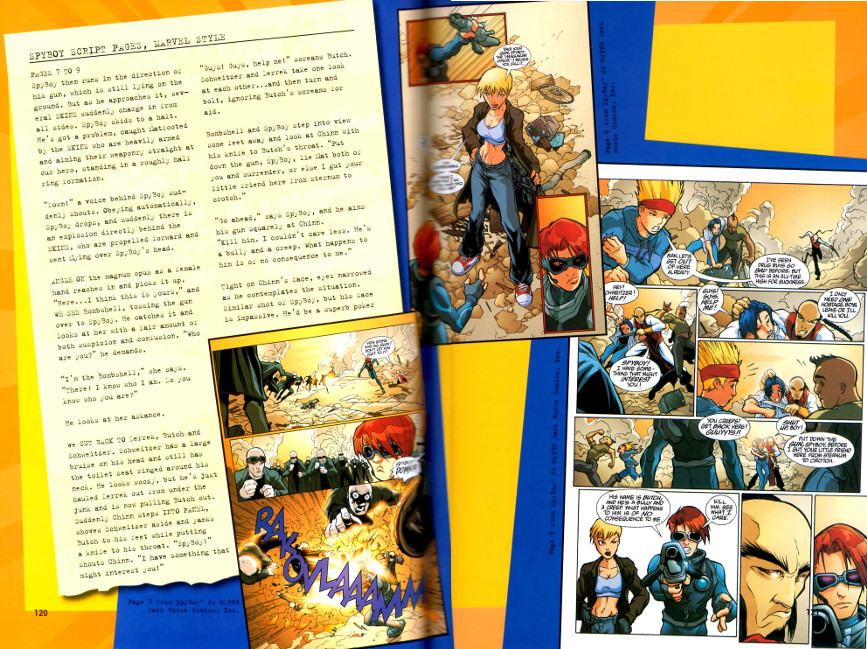

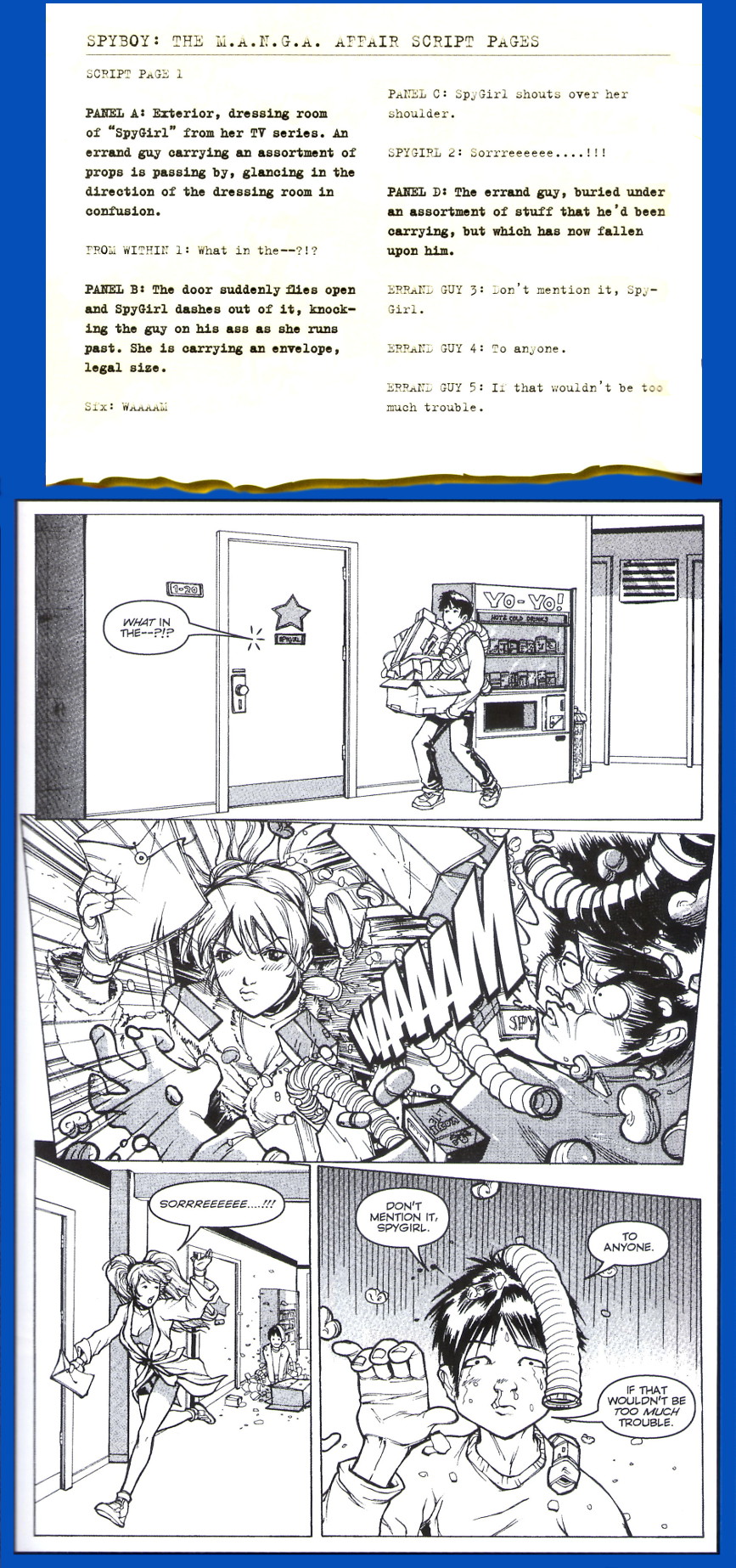

Finally, David has a detailed section on the mechanics of the script writing. Here he is also not markedly different from the earlier works examined. He cites the two conventional approaches: Marvel Style and Full Script. However, his coverage of these two approaches is far more detailed than either O’Neal’s or Moore’s work. In addition, he offers a comparison and contrast between the two methods using his Spy Boy comic.

Marvel Style

Full Script

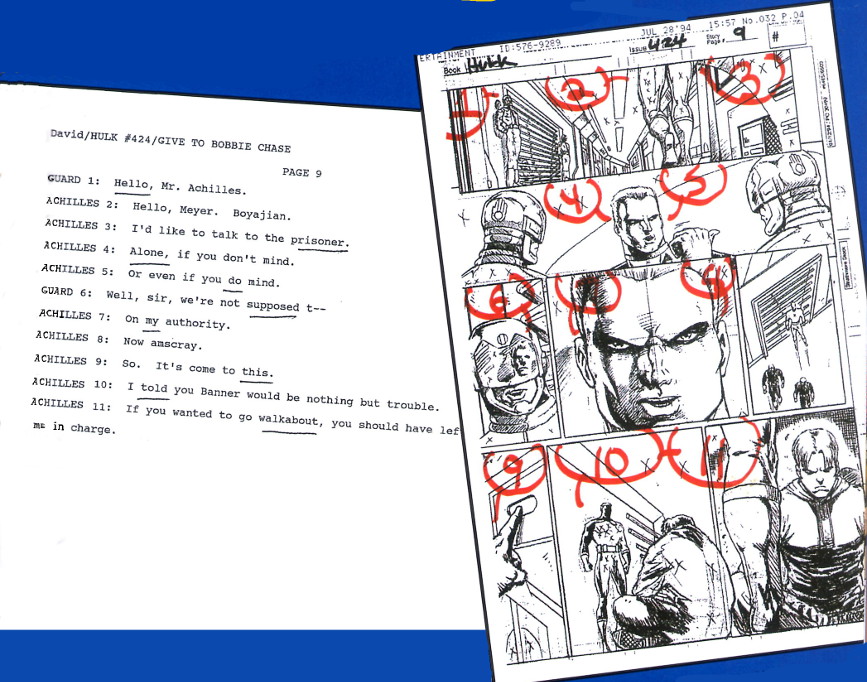

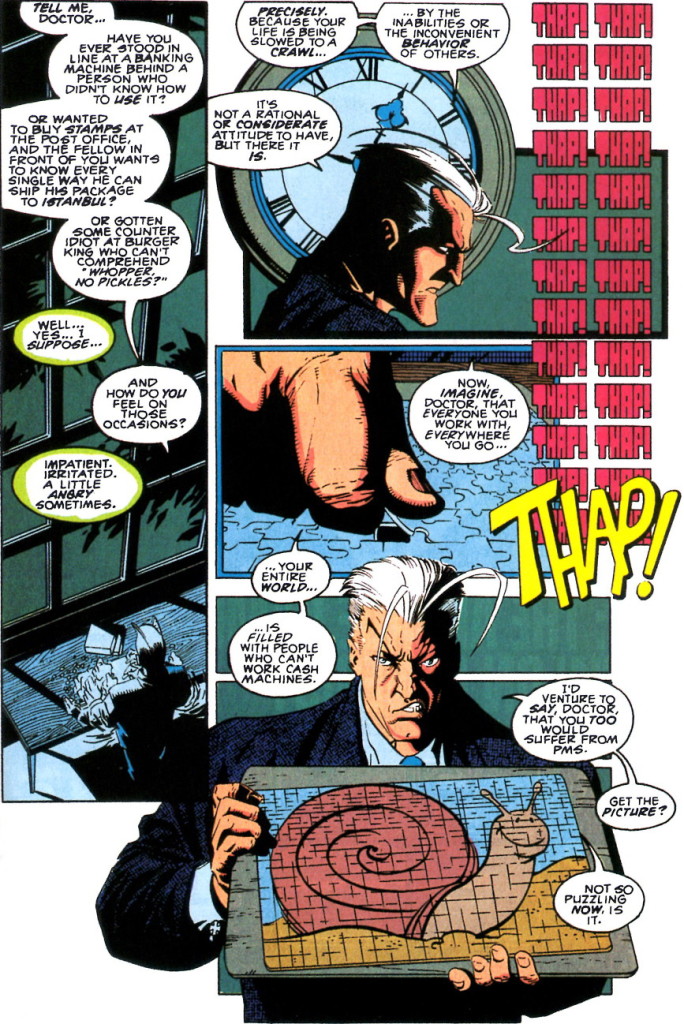

Finally, and a bit surprisingly, David discusses the stylings and placement of word balloons. Most of what he says here is not found in any other work and it was refreshing to see this point dealt with in such detail. Once again, he provides practical examples explaining the how-tos including this presentation from The Incredible Hulk #424.

Overall, I’ve found David’s book to be the best of its kind so far reviewed. It is a good read, fun and easy to get through and filled with information unavailable in either scope or detail in any of the other works I’ve reviewed so far.