Wild, Weird West – Part 3

The year is 2064 and the world is on the brink of apocalypse! Sound familiar? Except for the specific year mentioned, this tagline could be from a thousand bad and derivative B-movies that have come and gone over the years.

And derivative is just the word to describe East of West – and is just the word to describe just how good it is. Somehow the creative team of Jonathan Hickman, Nick Dragotta, and Frank Martin seems to have taken elements from lots of sources in classical and popular forms of literature, put them all in a blender, and hit the frappe setting. Out comes a comic that is compelling and archetypal in its story telling and beautiful in its line and color.

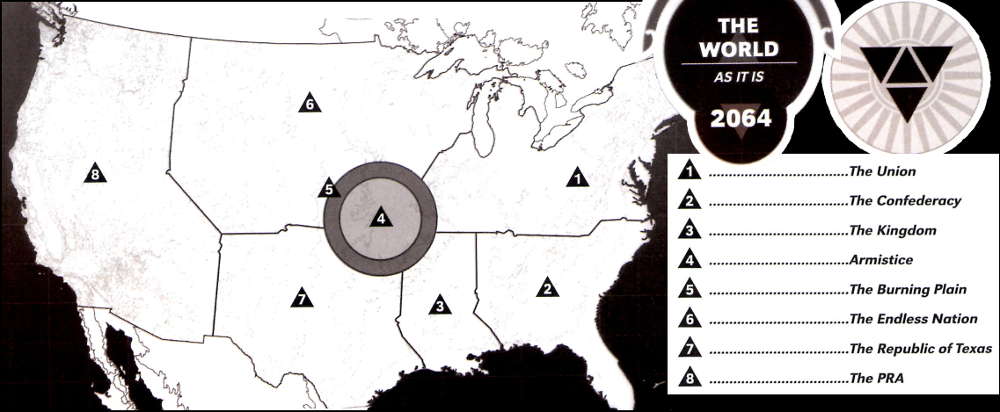

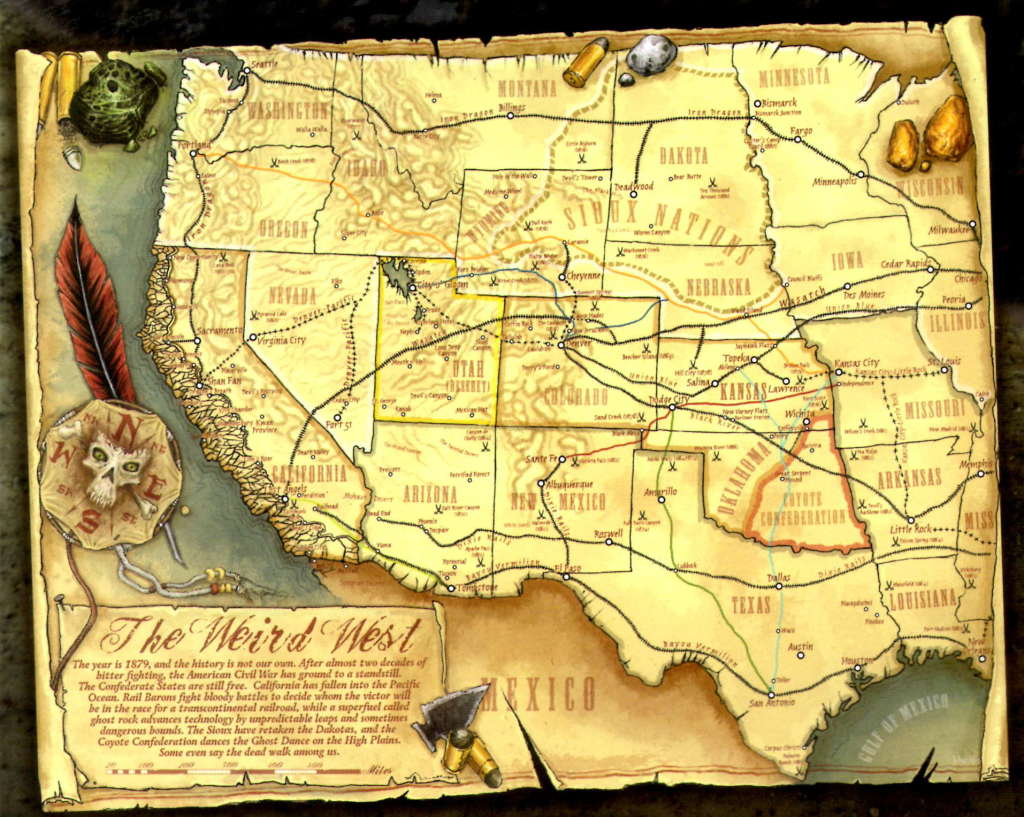

Perhaps taking inspiration from the Deadlands storyline (and indeed one of the locations is called by that name), they present a re-imagined future of the North American continent where the course of history is wrested from its familiar flow during the civil war.

This new history begins diverging in the year ‘eighteen hundred and sixty two,’ when Elijah Longstreet is caught up in the Third Great Awakening, abandons his position in the South’s army, and becomes a prophet. In 1863, all of the Native American tribes are united under Red Cloud to form the Endless Nation. Confronted with war on two fronts, the Union reaches a kind of détente with the South and the Endless Nation. This situation persists until about 1893 when a comet slams into the center of the continent at a place called Armistice. This catastrophe stops hostilities on all fronts and an agreement, referred to as the Accords, recognizing the Seven Nations of America is signed on November 9, 1908, at the impact site.

As a backdrop to these all too physical events is the spiritual component of The Message, a prophesy in three parts. The two largest components sprang from the pen of Elijah Longstreet and from the oral recitation of a ‘waking vision’ from Red Cloud. The final piece falls into place a half century later, provided as an addendum to Mao Zedong II’s, ruler of the People’s Republic of America, little red book.

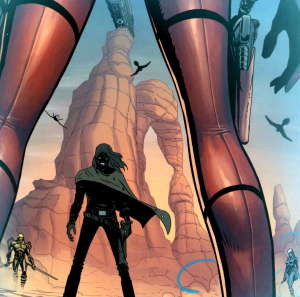

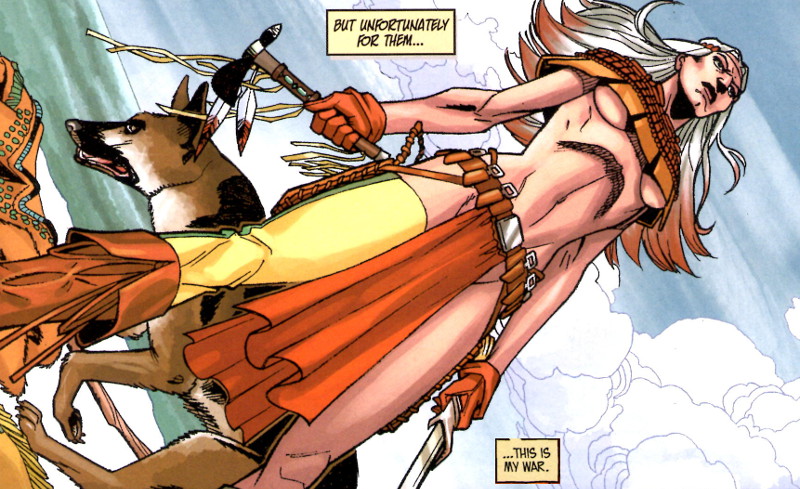

Fast forward about 100 years. The wild frontier of the old west is now juxtaposed with and accentuated by the monolithic architecture and the ubiquitous flying cars of futuristic world reminiscent of Blade Runner. And into a small frontier saloon, complete with swinging doors, walks a lanky cowboy all in white – white clothes, white boots, white hair, white eyes, and white skin. Accompanying him are two Native American witches, a large, imposing man named Wolf, and a shapely, thin woman named Crow – each equally monochromatic as their companion.

Here then is the Pale Rider himself, Death, who leaves a wake of destruction. But this embodiment of Death seems to be on a personal mission. More on this in a bit.

At the same time, further removed, we see a set of standing stones sitting in the wasteland, surrounding a brick circle decorated with four glyphs. Energy crackles, lights flash, and something seems about to happen.

Three figures then emerge from the ground, each sporting a single hue and a bizarre, childlike, appearance.

As they gather their senses, these three realize that one of their number is missing and, for that affront, they vow to kill him, followed by the world. It seems that they are the remaining three Horsemen. The red one is War, the one decked in green is Famine, while the blue-hued one is Conquest.

The Horsemen immediately set out to find their confederates in the human realm. A secret cabal of select members of each nation is aligned with the Horsemen. Known as the Chosen, these agents act secretly within their countries to hasten the end times.

Driven by the Message, each of them plays a pivotal role in bringing about the Apocalypse. Their secret club house is a tower located in the heart of Armistice,

which is run by a ‘priest’ named Ezra Orion, who was groomed from infancy by Conquest to be the harbinger of the Message.

The main thrust of the drama comes from the tension between the Horsemen. Sometime in the past, Death, who was almost entirely black in his previous incarnation, falls in love with Xiaolian, daughter of the Mao Zedong V, ruler of the PRA. Xiaolian and Death set up house, have a baby, and try to live a cozy little life together, but Conquest, War, and Famine will have none of it.

In a narrative told through fractured glimpses of 10 or 15 years in the past, the Horsemen conspire to separate Death from his wife. They then ambush Death

and attack Xiaolian and take her baby.

Death is now back, looking first for revenge, and then upon finding out that his wife and child are still alive, looking to re-unite his family. This may not be a very smart thing to do, since the son, now referred to as the Beast of the Apocalypse,

has been raised in a secret location where his mind and body have been trained to levels of fantastic mental and physical prowess, while any sense of moral awareness and compassion have atrophied.

And so begins a grand tale, epic in its scope, about love, betrayal, tragedy, and disappointment. Whether the little family will finally be re-united and at what cost to them, the Horsemen, the Chosen, and the rest of the world remains to be seen.

Along the way, we are treated to excellent exposition (all too lacking in today’s comics), striking art, and more cultural allusions than I can count.

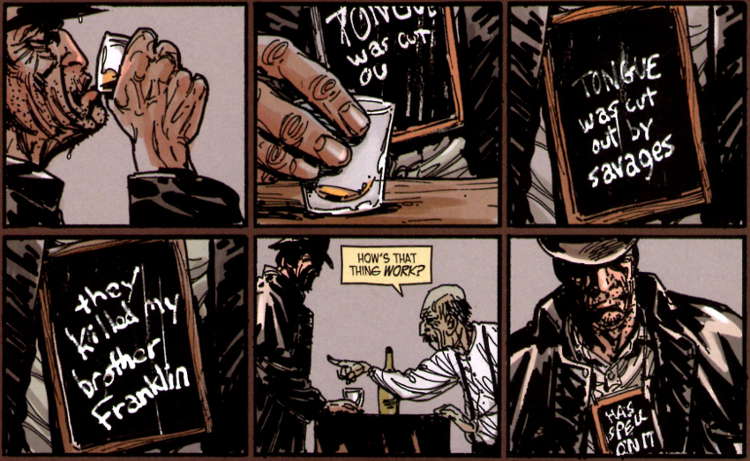

Hickman could easily lose the reader in his complicated set of interlocking motivations, ambitions, and occurrences, but he almost unerringly keeps the storyline easy to follow and the verisimilitude consistent. Minor flaws are present in the timeline leading up to the signing of the Accords at Armistice and in the use of the word Apocrypha (which literally means disputed or in error and so doesn’t or shouldn’t apply to the Message) but these are hard to find and easily ignored. The dialog orients us to the emotional states of the characters and their actions follow from these. No attempt is made to overly explain ‘how’ these things are occurring and so the story can proceed unencumbered with it mythology.

Dragotta’s art is also excellent and, as I said above, striking. It is very nicely complimented by Martin’s use of color – not only because the character colors are integral to the storyline, but also in conveying the raw intensity of a scene

or the stark horror of the events that bend many of these characters to the evil of the Horsemen.

There seems to be at least one homage to popular culture in every issue. Similarities to Deadlands, Blade Runner, Kill Bill, and other well-known stories abound. One of the most amusing is a parallel to the training that the Beast receives from a computerized system in his lair and the re-education of Spock at the beginning of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. In both cases, an emotionless computer is drilling an equally emotionless ‘man’ about the fine minutia of history, science, math, and logic. In both cases, the final question is “how do you feel,” which is answered by both trainees with puzzlement.

Finally, it is worth noting that East of West is reminiscent of the mythological work of Roger Zelazny. One of Zelazny’s favorite structures in writing a science fiction novel was creating a setting where the science of a world allows its practitioners to be regarded as figures pulled directly out of mythology. While the most famous of these is his novel Lord of Light, in which the main characters parallel the gods of the Hindu pantheon, the mythic and narrative structure of Creatures of Light and Darkness is much closer in tone and style. In Creatures of Light and Darkness, we find a fractured family trying to be re-united, an anachronistic world with ancient ideas mixed with modern technology, and a barely perceptible line between magic and science. Whether these similarities are coincidence or by design only Hickman, Dragotta, and Martin can tell.

When, after years of labor in America, Copernicus grows homesick, Tygian arranges that they both take a visit back to the old country. Perhaps sensing that they are an unwanted distraction, Tygian arranges for the Blackburne family to meet with a gruesome end, and then promptly disappears. Grief-stricken and vengeful, Copernicus perfects the improved pistol and comes back to the US with the Devil’s Six Gun.

When, after years of labor in America, Copernicus grows homesick, Tygian arranges that they both take a visit back to the old country. Perhaps sensing that they are an unwanted distraction, Tygian arranges for the Blackburne family to meet with a gruesome end, and then promptly disappears. Grief-stricken and vengeful, Copernicus perfects the improved pistol and comes back to the US with the Devil’s Six Gun.

and matter-of-factly tells everyone there that he has come to kill them all.

and matter-of-factly tells everyone there that he has come to kill them all.